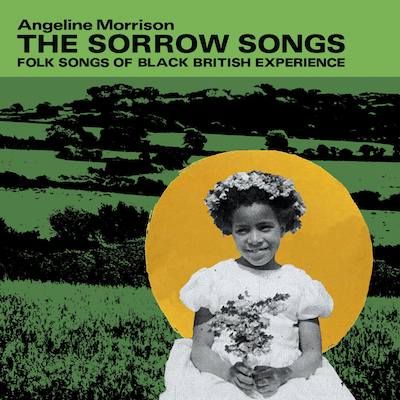

Angeline Morrison

The Sorrow Songs: Folk Songs Of Black British Experience

Topic Records

Out on 7 October 2022 – Pre-Order/Save here

Angeline Morrison‘s ‘The Sorrow Songs’ has generated a tremendous amount of interest since the announcement of its release on Topic Records, with it being hailed as one of the most significant and most anticipated releases of 2022.

The obvious question of whether The Sorrow Songs: Folk Songs Of Black British Experience meets these expectations is a resounding and unqualified yes. It would not be facile to suggest that the album will be viewed as an important, landmark release in the canon of British folk music.

As will be seen, many threads feed into the story of this project and release, all of which symbiotically contribute to the final offering.

With a lifelong interest in folk music, first sparked by listening to Shirley Collins play on the radio, Angeline attended folk clubs as a teenager, finding herself, more often than not, the only person of colour present. Fast forward to the time of the murder of George Floyd, and she re-reads W.E.B du Bois’ classic of African American literature, written in 1903, The Souls of Black Folk. Chapter 14 of the book, which gives this album its title, Of The Sorrow Songs, emphasises the importance of the body of folk song to the enslaved Africans and their descendants undergoing horrific experiences in America. This resonated with Angeline, herself a direct descendant of enslaved African people.

This re-reading also raised questions for her, “Where are people of colour in British Folk songs?”, “Why are there no equivalent of the African American folk songs, mainly spirituals, in our body of folk music?”, “Why is there no black voice in British folk music?” Although not widely known, people of the African diaspora have been resident on these islands for at least 2000 years; it seems inconceivable that tales of their lives and activities, whether ordinary or extraordinary, would not have been captured in words and music.

Angeline thus set out on a project to try to discover more, an exploration of the Black experience in British folk music. She had already decided to write the songs herself, with the support of Arts Council funding, in the style of traditional folk, based on the lives of real people and actual events, but, in her words, “re-storying” them, creating works of fiction based on reality.

Being awarded an Alan James Creative Bursary by the EFDSS enabled her to spend a week writing and researching in the Vaughan Williams Memorial Library at Cecil Sharp House. Here she confirmed that almost all of the songs referencing Black people or people of colour were negatively stereotypical and derogatory. Thus the sources for the actual songs on the album came from either oral histories or online research related to real lives and events of the historic Black population of Britain.

The next piece in this fascinating evolutionary tale of an album comes during lockdown in 2021 when Angeline sings a few of the songs on Eliza Carthy’s Folkroom on the Clubhouse app. Suitably impressed, Eliza offers to help and support, the result being that not only does she contribute violin and vocals and is responsible for the string arrangements, but she also produces the album.

Of the musicians that performed on the album, some were able to attend recording sessions at Cube Recording in Cornwall, while others recorded remotely. Thus, in addition to Angeline’s lead vocals, autoharp, double bass and glockenspiel, and the aforementioned Eliza, Cohen Braithwaite-Kilcoyne, Anglo concertina, melodeon, vocals, Clarke Camilleri, banjo, acoustic guitar, vocals, Hamilton Gross, violin, vocals, Rosie Crow, piano, vocals, Alex Neilson, drums, vocals, Mary Woodvine, vocals, plus one special guest, more of whom later, offer their fine talents to the project.

The songs themselves do have two stories from the twentieth century, but the remainder are taken from further back in time, emphasising Black presence throughout history. Lyrically, the approach is very much one of delivering in a straightforward narrative style; this, with careful production and subtle, restrained musicianship, permits the stories to take centre stage. Several songs also have their context illuminated by short spoken interludes, much like the ground-breaking BBC Radio Ballad documentaries created by Ewan MacColl, Peggy Seeger and Charles Parker that were broadcast between 1957-64. In the sleeve notes, Angeline gives these interstitials a “trigger warning”, and undoubtedly many will find them upsetting. Taken from listening to hours of mid-twentieth century interviews, the abhorrence of many of the comments indicates that the attitudes prevalent in the historical stories told here were still pervasive at the time of the recordings and, I venture to suggest, remain, in certain quarters, today in 2022.

The recording begins with one such interlude, Some Terrible Habits, which in a mere 27 seconds introduces perfectly the stark reality of the racism that was, (is), rife, “The coloured people have got some terrible habits, they use the back garden for toilets” … “Perhaps if there was less of them and more of us they might learn to live the way that we do”.

This leads straight into the opening song on the album, the uncomfortably sorrowful Unknown African Boy (D.1830). Released as the first single from the album, this was also the very first of The Sorrow Songs written by Angeline after she had read the distressing story of the wreck of a slave ship off the Isles of Scilly. A local newspaper article of the time listed items washed up on shore, including that of an unknown “West African boy”, estimated to have been around eight years old, who was later buried in St. Martin’s churchyard on the Isles. Written from the perspective of the boy’s mother, the opening sound of seagulls and the unfolding gentle lullaby bely the tragedy of a child cruelly abducted

‘He’s stolen away by English slavers,

With a cudgel blow, and a pointed gun’

As she pleads for his further safety

May the arms of the ocean be cradle for thee.

O earth, cradle my son for me

A truly riveting and emotionally draining song, the horror and inhumanity of this pernicious ‘trade’ is fully exposed.

This song is followed by another concerning a child abducted and trafficked into slavery, Black John, although in contrast, one with a far less harrowing ending. This tells the story of John Ystumllyn, who was recently honoured as the Britain’s first Black horticulturalist. Angeline recently shared on Facebook that John was an African in 18th Century Eifionydd, North Wales. He was brought there as a small boy to the wealthy landowning Wynne family (though it’s unclear whether he was purchased by the Wynnes or given as a gift to them). During his time with the Wynnes, he displayed a natural talent for gardening. Another gentle song, with vocals very much to the fore, the violin solo at the end very much in keeping with John’s love of the instrument.

Again with a child as the protagonist, the up-tempo The Beautiful Spotted Black Boy, with its fairground atmosphere and jaunty tune, is deceptive in the extreme. George Alexander Gratton (1808-1813), an African child who had vitiligo, was paraded, by his owner John Richardson in a ‘travelling freak show’ as a “spotted child”. The song is written as a conversation, or exchange of viewpoints, between John Richardson and George, who died somewhere between four and eight years of age.

‘Roll up and see my beautiful spotted black boy!

He’s a charming creature,

Dappled and speckled and spotted all o’er,’

‘Ah, but Sir, I wish that you had not bought me

With your thousand guineas,

Put me in cages and drag me about

The length and breadth of all the nation.’

The lyrics of Mad-haired Moll O’Bedlam present another song that paints a very vivid visual picture, a composition of which Angeline says, “It became a feminist song, as well as an anti-racist one.” Inspired as it was by former research into ‘mad hair’ in Western culture, it recounts the tale of a light-skinned Black 19-year-old who had been committed to an English psychiatric hospital, Bethlem Royal Hospital, or Bedlam, for the crime of “speaking the wrong way” to an officer of the law. The song has an unnerving opening and remains chilling and haunting to the very end, a masterful piece of writing.

With further high-quality songs that touch on the macabre, The Hand Of Fanny Johnson, the gentle Cinnamon Water, evoking a pastoral England which belies the Crimean experiences of Mary Jane Seacole, Hide Yourself, a short but not insignificant offering about the Liverpool Race Riots of 1919, where people of colour had to barricade themselves in their homes for safety, Cruel Mother Country concerning enslaved Africans encouraged to fight for the British in the American War of Independence, only for promises to be broken, and Go Home, the only piece in the collection not specifically rooted in a particular time, place or individual’s story, Angeline has ensured that her wish that the songs on the album be singable, that they will be sung in folk clubs, thus perpetuating the retelling of the stories, is more likely to be a reality rather than merely an aspiration.

The two remaining songs are both epics in different ways. The first, The Flames They Do Grow High has us returning to Wales for the story of twins, June Allison Gibbons and Jennifer Gibbons, born in 1963, their parents coming from Barbados to Britain in the early 1960s as part of the Windrush Generation. Bullied at school and retreating into a private world with their own language, they began writing as teenagers, but in 1981, having set a fire in an abandoned building, they were sentenced to indefinite detention in Broadmoor, the high-security psychiatric hospital. Eerie instrumentation on the song assists the lyrics in creating a dark atmosphere, entirely in keeping with the sad tale of ‘The Silent Twins’.

With a melody akin to something from the Sankey-Moody Hymn Book, Slave No More, the final track is anthemic in its power, with group choral singing of the highest quality. The story of Evaristo Muchovela, born in Mozambique and again a child sold into slavery; he was purchased in Brazil as a seven-year-old by Cornish miner Thomas Johns. The latter appears to have cared well for Evaristo, and the two are to be found buried in the same grave in Wendron Churchyard. The tombstone bears the inscription,

“Here lie the master and the slave

Side by side within one grave

Distinction is lost, and cast is o’er

The slave is slave no more’

As Angeline states, “When I first visited the grave, I knew I had to sing this inscription. I could hear Martin Carthy’s voice reading it out, playing the role of the Vicar at the burial… so it really was a dream come true when he agreed to do it.” Indeed, Martin recites these words as he plays the part of the priest at Evaristo’s funeral and, in so doing publically lends support to the significance of this project.

In an earlier interview with Folk Radio UK (read it here), Angeline told how she wanted the stories of historic British Black ancestors retold through song. She adds, “…telling stories through song is common to all cultures and the people whose stories are made into songs are those we remember”. The Sorrow Songs tell those stories so well, and they are now there for future generations to be remembered.

The Sorrow Songs is a ground-breaking album; the music is excellent throughout, beautifully enhanced by the album’s exemplary artwork and packaging. The additional notes are not only informative and enjoyable to read, but they also encourage you to explore this history further.

As a gift to the folk community, The Sorrow Songs will connect with the hearts and emotions of the listeners; as a gift to her ancestors, Angeline has more than done them proud.

The Sorrow Songs is Out on 7 October 2022 via Topic Records – Pre-Order/Save here.

On Tour in October – TIcket links and details here: https://www.bandsintown.com/a/7187010

More: https://linktr.ee/angelcakepie