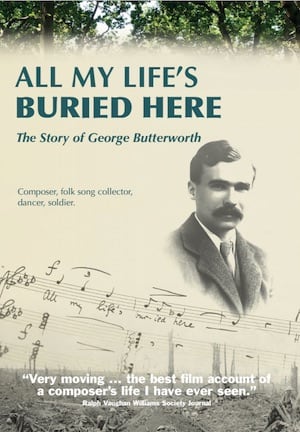

All My Life’s Buried Here: The Story Of George Butterworth (DVD)

(A film by Stewart Morgan Hajdukiewicz)

George Butterworth (1885-1916) was a pioneering English composer who together with his friend and mentor Ralph Vaughan Williams was a leading member of what has been described as “a radical group of composers in the Edwardian years whose music was profoundly influenced by the traditional music of the English rural working-class” – i.e. folk song. He promulgated a specifically English identity in “classical” music, which for years had been constrained by what Vaughan Williams termed “the Oxford manner in music, that fear of self-expression that seemed to be fostered by academic traditions”. This English national identity in music was achieved through the incorporation of elements drawn from folk music, the “hidden and lost English music” of true artistic and cultural purity; in effect, then, it was folk song that freed Britain’s art from its academic surroundings. (Additionally, however, account needs to be taken of G.K. Chesterton’s reactionary poem The Secret People, which includes the memorable line “For we are the people of England and we have not spoken yet”, which complements the concept implied by the views of folksong collector Cecil Sharp).

This DVD is a singularly compelling account of the story of George Butterworth, whose life was brutally cut short at age 31 when he was killed during active war service on the front line at the Battle Of The Somme in August 1916. It is wholly fitting, then, that the centrepiece of this DVD, its 97-minute “main feature” portrait documentary, should begin and end in a total, respectful silence. The chronological account of Butterworth’s life which forms the core of the film is framed by sequences taken at a ceremony at the village of Pozières, where on 5th August each year the local population gathers in memory. Tragically, Butterworth lived too short a time to be fully recognised for his achievements in the musical field, and inevitably there will always be tantalising “what-if” speculations, especially in the light of comparisons with the longevity of his fellow folksong-collector Vaughan Williams, who was to live on into his mid-80s (he died in August 1958) and who left behind an incomparable legacy of pioneering and innovative music covering all major genres and disciplines. But what this documentary emphasises throughout is that in order to understand Butterworth, the man one has to be cognisant of the temporal context in which he led his all-too-short life.

In doing this, the film presents much information that is both new and revealing, and the section on folk song collecting, in particular, delivers insights that well place that essential context for us. Interviews with his contemporaries and specialist scholars and commentators provide nuggets of perspective to just the right degree to inspire further investigation. The music and songs are also not forgotten, and the examples interspersing the commentary and interviews are well-chosen. Separate audio recordings of two individual songs collected by Butterworth in Sussex – The Banks Of Green Willow and Green Bushes – are given (performed by Peta Webb) among the various companion supplements to the main feature. And the main narrative includes some exclusive new live renditions of Butterworth song settings performed by Roderick Williams and Iain Burnside. The limited-edition DVD & Blu-ray package also includes a 20-page booklet containing newly commissioned articles by Shirley Collins, Malcolm Taylor, Katie Howson and Anthony Murphy.

Butterworth was an avid folk song collector, genuinely excited by the discoveries he was making. He made “qualitative evaluation” comparison studies of melodies of the songs he had collected, and, like Vaughan Williams, was particularly interested in the distinctively modal nature of the tunes. (Even so, that’s not to say that the texts themselves were of less importance to Butterworth.) He also had an passionate – and practising – interest in folk dance, and the development of these parallel interests into his own compositions was with hindsight the most natural of consequences. His best-known composition was the orchestral idyll The Banks Of Green Willow, which uses the melody of that folksong as the basic material for its musical development. Another key work in his output was a series of song-style settings of A.E. Housman’s poems from the collection A Shropshire Lad. And yet, less than two dozen of Butterworth’s own compositions survive, for he himself destroyed a great number of them when he volunteered for war service. The film discusses at some length (and commendably accessibly) the nature of Butterworth’s music, its essence of Edwardian England, its evocativeness which in an obvious way represents its era and yet nevertheless transcends its time, and in doing so proves to be for all time. It also transcends received mythology of the era.

The most poignant segment of the film, inevitably, is its final one, which begins with Butterworth’s internal crisis of conscience and heart-searching, a state of mind where consideration of life’s perplexing nature led him to the view that war seemed to provide a release. He became caught up in the mechanics of war life, immersing himself enthusiastically in the intensity of war service, and enjoyed a rapport with his fellow-soldiers. Music activities just became displaced, almost assuming a status of irrelevance in that context, and this is likely to have informed his decision to destroy several compositions which he thought below-standard. The tragic chance circumstances leading to Butterworth’s death are recounted in an almost matter-of-fact manner, which only emphasises the random nature of war and its casualties. This also makes the interpolation of part of Peter Bellamy’s Kipling setting (Soldier, Soldier) all the more starkly moving at Butterworth’s final moments. In the chaos of war, he was buried where he fell, and his remains were never subsequently identified. The oft-peddled phrase “cut down in his prime” feels never more apt.

As biog-documentaries go, All My Life’s Buried Here must be judged one of the finest and especially well realised: couched in a style that reflects the character of its subject, sympathetic without being cloying, authoritative without being dryly scholarly, and its plethora of information put across in such a way as to genuinely illuminate our perception of its subject and his achievements. It is truly compelling viewing and something of a benchmark in its field.

Order here: www.georgebutterworth.co.uk