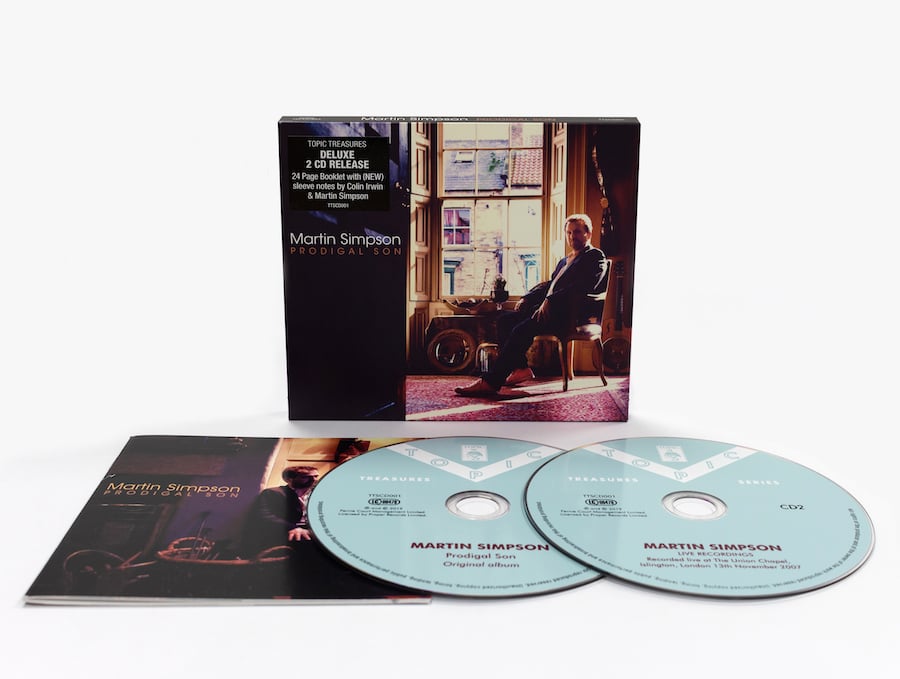

Martin Simpson – Prodigal Son (Deluxe Edition Reissue)

Martin Simpson – Prodigal Son (Deluxe Edition Reissue)

Topic Records – 22 March 2019

Reviewing a landmark album you only know from its cultural footprint is the ultimate hospital pass on a greasy pitch in driving rain with take-no-prisoners defenders in close attendance. You can’t win. Great albums are invariably a combination of the right artist with the right audience with the right songs at the right time for everyone involved. If you come late to the party and yet it turns out that what you’re listening to for the first time is indeed the enduring work of timeless genius that will change your life forever that everyone says it is, all well and good. If it’s not, well, you’re left wondering what all the fuss is about. What exactly are you missing? Is it you? Is everyone else wrong? Is it just that you’re meeting each other at the wrong points on your respective cultural curves? Or is it actually just not all that good when it’s been removed from its time and place?

Which brings us neatly to Topic Record’s re-release of Martin Simpson’s 2007 album Prodigal Son. I know that in a lifetime spent producing consistently excellent albums, this is considered to be the one. Peak Simpson. I know that it emerged following a period of personal flux precipitating and coinciding with Martin’s return to the UK after 12 years in the USA. I know that it was his fourth album for Topic following 2002’s The Bramble Briar; the deep-mined American blues of 2003’s Righteousness and Humidity and the Celtic-stylings of 2005’s Kind Letters. I know also that this is the album where everything came together: Martin’s abilities as one of the world’s foremost acoustic guitar stylists; his enduring class as an arranger and interpreter of other people’s material; and his deep personal connection to the folk traditions of two continents. I know that all of this collided with Martin’s emergence as an artist capable of writing from a deeply-felt personal point of view with sharp clarity and great sensitivity and as a singer capable of communicating the powerful emotions his playing conjured up.

I know all of this because I’ve read it and I’ve heard other people say it. What I haven’t actually heard is the album itself. No pressure, then.

If the devil is in the details, here they are. It’s the first release on Topic’s new Topic Treasures imprint. As well as the 15 tracks of the original album, you also get a stellar set recorded live at Islington’s Union Chapel on 13th November 2007, where Simpson is ably and supplely accompanied by Andy Cutting, Andy Seward and Kellie White. New sleeve notes by Colin Irwin and Simpson himself fill out an accompanying 24-page booklet describing the album’s genesis and production. It’s a good, well-thought-out package. In the liner notes Irwin suggests that any discussion of folk’s greatest albums would have to include Prodigal Son alongside Dick Gaughan’s Handful of Earth, Nic Jones’s Penguin Eggs and Eliza Carthy’s Anglicana. That’s not a debate into whose waters I’m going to stick my toes in. It should be taken as a sign as how highly this particular set is rated that it was chosen to launch the new reissue series celebrating the best of Topic’s history – especially when you consider some of the names who’ve graced the label’s roster over its 80-year history.

So, does the album deserve its reputation?

Yes, is the short answer.

The longer answer runs something like this:

Packages like this work on many levels, including commercial and marketing imperatives. But the reality is that all of that stands and falls on the music within – and the music here is utterly fantastic. Martin Simpson’s consistent excellence as an acoustic guitar player and his mastery of multiple styles and approaches has, I think, numbed us to just how good he really is. Listening to Simpson play is like watching Roger Federer play tennis on the Centre Court of Wimbledon – the apparently effortless grace and control hide the amount of hard work and dedication it takes to operate at such a rarefied level. The first 30 seconds of Bachelor’s Hall serves as a salutary reminder of just what we’ve got on our hands. The opening statement of the theme, the quicksilver fluidly seamless movement between fretted notes and harmonics and the sheer variety of right and left-hand techniques before the vocals enter is guitar playing not as the sequences of patterns and runs it often devolves into, but as the expression of personality and emotion it should be. The level of technical ability is fearsomely high throughout but the playing is always at the service of the music. Simpson, along with others like Tony McManus, are responsible for the current exceptional levels of technical facility that exist in the six-string portions of the folk and traditional worlds, but his playing has also been a pointed reminder that the music being at the service of the player is a failure of virtuosity.

Bachelor’s Hall’s opening melancholic lament for lost love draws from Dick Connette’s version and the tune of Pretty Saro to great effect, reflecting Simpson’s deep, enduring and absolute love of American traditional music. It gives way to Frank Proffitt’s Pretty Crowing Chicken. There is something in Martin Simpson’s touch, his tone, his note and rhythmic choices that means that you always know when it’s him playing even when shifting to clawhammer banjo. It’s not just the Sobell guitars and Highlander pickups used here. These elements have been consistent throughout his playing. This is a great arrangement and it sounds like it’s great fun to play. Lakes of Champlain draws together its multiple fractured treatments to present a simply gorgeous arrangement where it’s possible to hear the early flowering of the musical relationship between Simpson and Andy Cutting. Listening back, I can hear how the voice that I first came to with 2013’s Vagrant Stanzas album developed from Prodigal Son on, but there is still a richness and a nuance to the vocal delivery that gets to the heart of the story in each song. Andrew Lammie’s tragic narrative is invested with pathos and dignity, with Cutting again providing almost telepathically sympathetic accompaniment alongside the Northumbrian pipes of Alistair Anderson. Poignantly, given Britain’s shocking susceptibility to attempts to wrap all in the flag, Little Musgrave stands as a reminder of just how violent, brutal and thuggish the ruling elites were and are. Yes, it’s a tale of reckless love (should there be any other kind?), bolshie insubordination, jobsworth tattle-tales and retribution, but Lord Barnard’s actions and Musgrave’s demise shows the lengths to which they will go to hold onto to what they’ve got – whether that be power, their land, or their faithless wife. It is a cracking tune, with a great guitar arrangement. As for The Granemore Hare – it’s been a favourite song of mine from childhood in Northumbria and it’s done stunning, stunning justice here. Simpson’s decision to hold off singing it until he felt he was ready pays dividends. It’s just a great version.

One of the key features of Martin Simpson’s development as an artist has been the ease with which he’s straddled the traditions of British folk and the American traditions. The shift of gears to Good Morning Mr. Railway Man, Duncan & Brady and Louisiana 1927 offers a study in contrasts and connections between both worlds to the enrichment of both throughout the album. There’s never the sense that Simpson is playing the blues as a move or by rote. It’s never performative or a pose. It’s always deeply felt and committed in a way that only someone personally invested in these musics could pull off.

Ink has previously been expended suggesting that this is the album where Simpson began to write about his own life as well as he’d previously interpreted and arranged the material of other people’s. The suggestion has been that this represents his emergence as a significant artist. I think this does him a disservice. You don’t start your recording career in 1976 (Golden Vanity) and reach the level of artistic and professional acclaim that Simpson did prior to the release of Prodigal Son simply because of technical ability and a facility to inhabit and interpret traditional music. As such, although She Slips Away, Mother Love, Never Any Good, and Kit’s Tune / When A Knight Won His Spurs are powerfully invested and associated with Simpson’s own experiences they would still be incredible evocations of the variety, vicissitudes, joys and tragedies of the human condition even if we didn’t know their backstories. They’re simply wonderful pieces of music. They absolutely nail their emotional contexts: a son and his father; a mother and her baby; two adults meeting at the right time; the joy of a daughter.

In conclusion, it’s important to note that albums work as cohesive wholes. An album with three great tracks and ten forgettable ones is not a great album. It’s a missed opportunity. What’s significant about Prodigal Son is that although outstanding tracks abound, this really is the one where it all came together. I don’t say that at the expense of Martin Simpson’s other work. He’s always been consistently good. But Prodigal Son is a real statement of … intent; of who he was growing up as a flashy young buck in Lincolnshire; of who he became in America; and who he was when he returned to British shores. It’s an album that indicates just how deeply Martin Simpson has connected to the traditions of his chosen musics and how deeply he has studied and felt them whilst also connecting to his own life circumstances and the world he found himself in. I don’t want this to slip into hagiography. In the interests of full disclosure, I can honestly state that Martin Simpson has no idea who I am; I’m not being paid to write this review, and I won’t get any kickback from the record company. It just really is a great album – bolstered by a live set that is equally good. If you haven’t heard it, you should. If you have, you should revisit it.

Photo Credit: David Angel