We described Declan O’Rourke’s outstanding album Chronicles of the Great Irish Famine (reviewed here) as telling ‘stories of the famine that needed to be told in a moving and evocative way’. It is no surprise that Declan was nominated for best original track, for The Great Saint Lawrence River, in the 2018 BBC Radio 2 Folk Awards and that he has been nominated both for best original folk track, for Along The Western Seaboard, and for best folk singer in the inaugural RTÉ Radio 1 Folk Awards which will be held at Vicar Street in Dublin on 25th October.

I talked to Declan about realising the musical setting for the songs, what is it has been like playing them live, remarkably finding the ruined cottage of the family whose story started the whole project and why he is performing the album in its entirety at a special charity concert in aid of Action Against Hunger at the Royal Northern College of Music (RNCM) in Manchester next month.

Chronicles of the Great Irish Famine was 15 years in the making and deciding on the right musical form was a journey in itself. Declan described how the music came together.

“It was such a long gestation, in so many ways, for a start with the research and the writing. Making the record was really the very last thing. One of the decisions I made early on was to not record demos of these songs as I was writing them because it was such a long process that I wanted to wait until they were all finished before I added other instrumentation. So, I kept them with practically just me and the guitar. My hope was that when the project came together they would sound like a collection that grew together and reflected the way I changed over time as well. That made it all the more exciting for it to happen because it was all fresh the way they were coming to life, there were lots of surprises and things that I had imagined came into being suddenly.

“I got hooked up, maybe about a year, 18 months before the record was made, with the Abbey Theatre [in Dublin] and they had the idea of trying to turn the whole thing into some kind of theatrical show. We didn’t know what that meant but the aim of that was to also try and gather some attention to it and maybe help to fund the recording. Ultimately the theatrical thing didn’t happen but what I did do at that time was gather six or seven of the musicians together and we played through about maybe half of the songs for three days. It was a huge step towards the whole thing – it started to show itself as to what it would be. Until that point, I had been in two minds. I wasn’t sure if it was a good idea to go full traditional or try and contemporise it a little bit. Part of me was maybe reluctant to admit that a traditional music setting was right because I knew that it would put it into a box. All but one of the tracks on the record are written from the point of view of the time that the actual events took place, so it made sense to record it closer to the sound of that time. It was a different direction for me, but I had to allow it to do what it wanted to do in the end”.

Declan has been playing the material live since the album was released last November. He revealed some of the fears and challenges he faced in taking it to the stage.

“Playing the material has evolved under our feet because the first night we got on stage to play it I still wasn’t sure if was going to talk or not. I was partly afraid that this might go so far into the realm of academia in terms of subject matter that there would be these scholars coming and saying, ‘you can’t say that’ and that was weighing on my mind. Offstage of course there were all kinds of gags and jokes happening between the band but taking it on stage it was obviously more sacred. It became clear that you had to contextualise some of it for the audience and I was also keen to relate it to things that are still happening today and to do that I had to speak. The more nights we played the more it loosened up until it came to the point where we were actually having fun as well. Some of it is still quite formal but there is no script so the information I might give about any particular song might change from night to night.”

The Great Irish Famine and the history behind it isn’t something that is widely taught in schools – not least how the Irish population were forced into a monoculture leaving them incredibly susceptible to potato blight. Despite this, the response to the Chronicles of the Great Irish Famine has been exceptional.

“From the very first night, we have collectively been blown away. We’ve had a spontaneous standing ovation every single night anywhere we’ve played it so far. I don’t know how much this means but, compared to other concerts I’ve had throughout my career, different people appear to have been much more drawn into it. The response feels really genuine. The aim all along was to present the kind of universal element of each story to people. What I was searching for were these moments in personal accounts that anybody could relate to – just the really human element in it all.

“One thing I’ve been really happy about has been the response in the UK because it was just the same that we had here [in Ireland]. I think a lot of people who came to the show weren’t aware that this was going to be a show about the famine. They thought it was [going to be] my music in general. I think the relationship between Ireland and England is incredible in how far we’ve come. It has been great to also connect this with people who maybe aren’t from an Irish background. Going on stage with it in England for the first time in April at The Borderline in London was like going on stage with the material for very first time. Even in different circumstances and surroundings, and with a standing audience, we still had this great outpouring of emotion at the end of the show.”

The story about the Buckley family, which Declan read in John O’Connor’s book The Workhouses of Ireland, was the starting point for the whole project. The song, Poor Boys Shoes, tells of a father whose two children are dying in the workhouse in Macroom. His wife is also suffering, he carries her home, only for her to die while he tries to keep her feet warm, they are both found dead the next morning. Declan told me the remarkable story of how he came to visit the ruin of their cottage.

“I did a gig recently in Skibbereen. Skibbereen was reputed to be the worst affected town in Ireland in the famine, although it may be that it just received the most coverage. There was an illustrator called James Mahoney living in Cork who was commissioned by the Illustrated London News to report on what was happening. What he wrote almost changed the way the news was presented at the time because he told it in the first person: he wrote ‘I am witnessing this’ which was unheard of at the time. Skibbereen did anyway become the town that was synonymous with the famine.”

Mahoney’s illustrations and reports, published in early 1847, received huge attention and moved ordinary English people to contribute towards relief efforts. Tim Pat Coogan, in his book The Famine Plot, described the effect that Mahony had as comparable to that of the BBC reporter Michael Buerk when he reported on the famine in Ethiopia in 1984.

“After the concert in Skibbereen a man approached me, and he told me that he came from a place called Macroom, which is near where I knew the family in Poor Boys Shoes came from. I’ve searched for years to find out more information about these people and it has been just impossible. The records from the workhouse at that time don’t exist. All we have to go on is the account of a man who lived nearby, and it was written famously into this book published in Irish [Mo Scéal Féin by Peadar Ua Laoghaire, 1915 – the Buckley family at some point lived on the land owned by authors family]. Any attempt to find out anything else about them over the years has come to nothing.

“As the man was leaving the gig, I said to him in passing, ‘have you heard of a place by the name of Doire Liath [where Ua Laoghaire describes the Buckley’s home as being]? He said, ‘I haven’t but leave it with me’. He went away and called somebody, who called somebody, who called somebody else. A couple of days later we ended up looking at the remains of the Buckley’s cottage, which, along with others nearby, had been covered in brush and gorse for decades but recently there was a gorse fire and it was exposed. They asked me to sing the song and it was just an absolute hair-raising, profound experience. I was so moved there that I realised my job is not done. I thought that after 15 years that I had completed it, but I think now I’m going to be doing something about this for the rest of my life. It just became clear to me that it’s not finished. I love history, I’m fascinated with it, but I don’t know if I’ll ever completely spend as much time on any single subject, but then at one time I would never have seen Chronicles of the Great Irish Famine coming either.”

Some 170 years after the Irish famine, the reality of widespread and increasing hunger across the world in the 21st century – affecting 815 million people in 2016 – is something Declan wants to make a connection with. I asked him how the charity concert in Manchester in aid of Action Against Hunger came about.

“A man called Liam Ferguson, who saw the show in Bury in April, was so moved by the whole experience that he wanted to do something linked to it and so he’s put this whole thing together which is brilliant because you couldn’t ask for a better result than it makes a difference along the way and that‘s hopefully what this will do. Hunger affects 11% of the global population still now which is just incredible. They are struggling to provide safe water and adequate nutrition in 50 countries around the globe. The way we see news is very strange. In a way, the world has become very small because you can access somebody anywhere at any time but still, in general, we only really pay attention to local news – if it’s not in your backyard, you’re not too worried about it.”

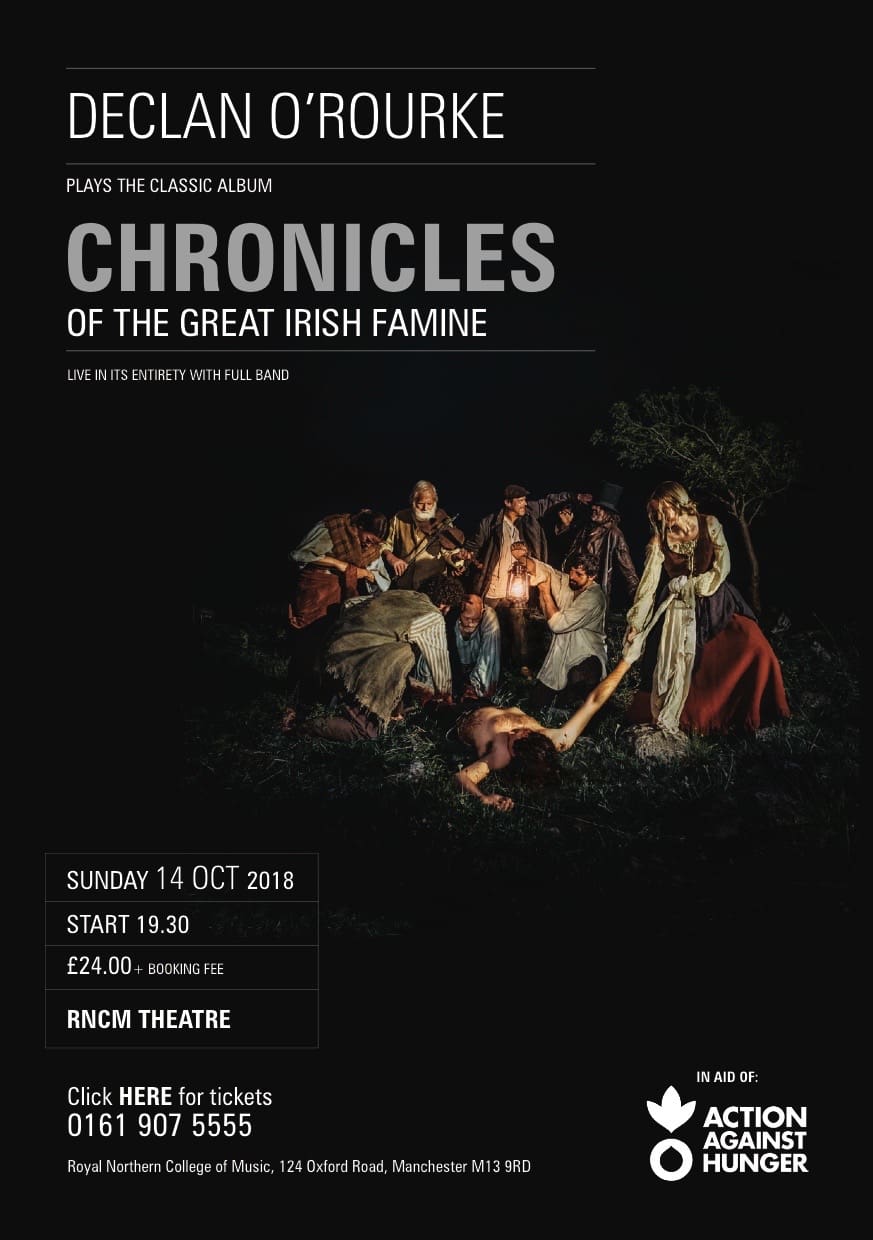

Chronicles of the Great Irish Famine in aid of Action Against Hunger

The special charity concert of Chronicles of the Great Irish Famine in aid of Action Against Hunger will be held at the Royal Northern College of Music (RNCM) in Manchester, on the evening of Sunday 14th October at 7 pm. Tickets via https://www.rncm.ac.uk/performance/declan-orourke/

Band members to include:

Declan O’Rourke guitar, vocals

Jack Maher guitar, banjo, mandolin, vocals

Floriane Blanche harp, vocals

Chris Herzberger fiddle, viola

Dan Bodwell bass

John Sheahan fiddle, whistle, mandolin

For readers who can’t go to show but would like to support the charity, donations can be made at https://www.justgiving.com/fundraising/liam-ferguson5

Chronicles of the Great Irish Famine is available on Warner Bros now (Amazon).