Next Friday (August 15th), sees the release of Kin, the new album from Fletcher Tucker. In his review of the album, Thomas Blake concludes that “Kin genuinely sounds like nothing else, an album full of ritualistic sonic patterns and precisely detailed shifts in tone and mood, an album rooted less in a single landscape than in the very idea of landscape, and all the ancientness and weirdness that implies.”

Earlier in the review, he notes, “Its human element speaks the language of ritual, that most ancient of tongues, with which we first learned to converse with the seasons and the weather and the animals, dangerous and placid. While it moves towards repetition and the hint of hypnosis, it is, in reality, an earthy rather than a cosmic music. And it is more active than our current ideas of ambience would usually permit: it roves over rocks like a clear stream, or scales trees like a moss.”

Tucker, who is also the founder of the highly respected Gnome Life Records, will take his album on the road shortly, on which he recently shared: “Each performance will take place in a non-profit space dedicated to community and/or the esoteric underground. Every show is with the brilliant master of synesthetic synthesis LFZ (aka Sean Smith)! Be prepared for fecund ceremonial vibes from your’s truly. I hope you’ll join me in the celestial compost heap.”

While I always look forward to seeing what artists will share in our Off the Shelf series, in which we ask artists to present objects from a shelf or shelves in their homes (or space) and discuss them, I was particularly excited to read this one and it does not disappoint.

Tucker’s bio opening reads: Fletcher Tucker (born 1983) is an interdisciplinary artist and practitioner of animistic, earth-reverent skills and philosophies, residing on the unceded Esselen tribal lands now known as Big Sur, California. I’ve been something of an avid reader of Beat Generation literature since I was 16, when I first read Dharma Bums. So it was no stretch of the imagination to liken the ‘earth reverent’ Tucker to Japhy Ryder, one of Kerouac’s characters from Dharma Bums–one moment leaping from rock to rock in a state of constant spiritual bliss, then being able to ground themself and switch to utter stillness:

We went over to the promontory where we could see the whole valley and Japhy sat down in full lotus posture cross-legged on a rock and took out his wooden juju prayer beads and prayed. That is, he simply held the beads in his hands, the hands upside-down with thumbs touching, and stared straight ahead and didn’t move a bone.

from Dharma Bums, by Jack Kerouac

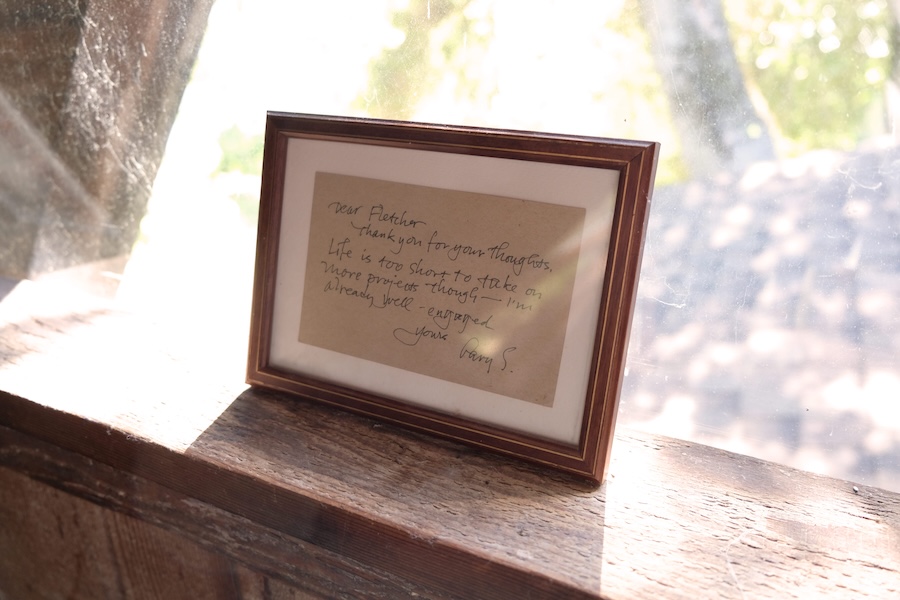

So, yeah, this album, and now this Off the Shelf feature, have been a beautiful trip; take a look at that letter from Gary Snyder below (he is now 95): the American poet, essayist, lecturer, and environmental activist, upon whom Japhy Ryder was based.

This one went way beyond my expectations and will no doubt open some new paths as these things often do, just like that old copy of Dharma Bums.

Thank you, Fletcher Tucker.

Enjoy folks.

Off the Shelf with Fletcher Tucker

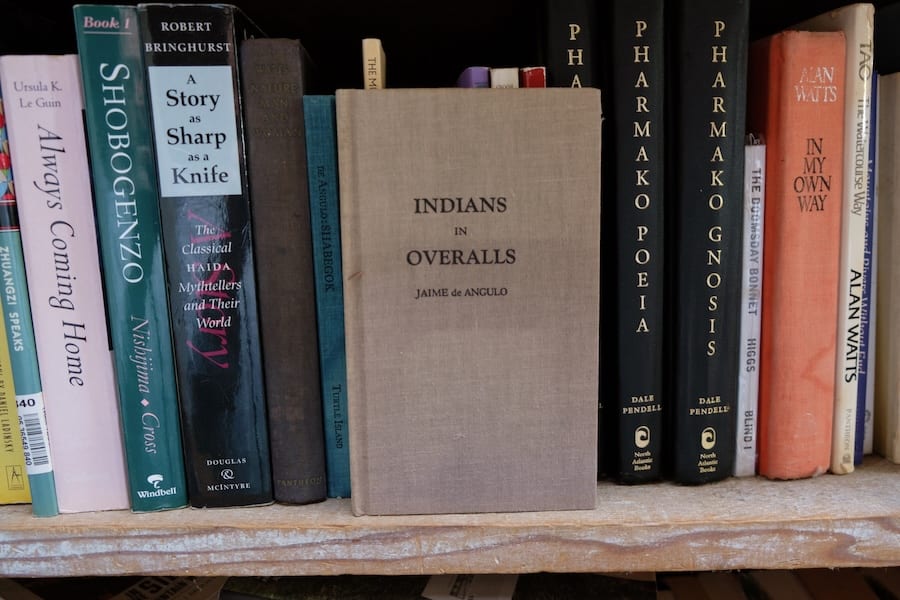

Indians in Overalls by Jaime de Angulo

A self-published first edition of Indians in Overalls by Jaime de Angulo lives on my shelf—a talisman from one of Big Sur’s wildest heart-minds. De Angulo was an eccentric poet-mystic, cowboy doctor, bohemian polyglot, and ethnolinguist. He lived with, and listened to, this land with profound intensity and passion. He was a translator for, and a welcome guest among, so many of California’s first peoples, and was fluent in something close to fifteen tribal languages by the end of his life. His work is strange, ecstatic, unclassifiable—part field study, part shamanic journeywork. My favorite historic Big Sur artist, he’s long been a creative north star for me. Not just because I admire his writing, but because I actually live on the plot of land he homesteaded. I tend his orchard now—ancient persimmons, mulberries, apples, and avocados still fruiting. They nourish my family, as his words have nourished me.

Stone-age Fire-tending Tools (deer antlers and elderberry fire-blower)

My home is heated exclusively with a woodstove. In the winter months, I’m building fires first thing every morning, and tending them all day long. Since fire plays such an elemental role in my homelife, I’ve chosen to make my own Stone-Age-style firetending tools—tools which distance me as little from the fire as possible, and, in fact, deepen my connection to the more-than-human world and my own ancestry. The antlers pictured are sheds from a black-tailed deer; I found them when I was about 7 or 8 years old in the oak forest that surrounded my grandparents’ home in Northern California (I treasured them throughout my childhood). I use the antlers to reposition burning logs in the stove, much the same way you’d use an iron poker. The cylindrical implement is a fire-blower I crafted from an elderberry cane. By blowing through it, I can send a focused jet of air into the heart of the fire, stoking it like bellows. Elder is the most sacred plant in the pre-Christian Scandinavian tradition. My Swedish ancestors had hundreds of magical, medicinal, culinary, musical, and utilitarian ways of working with elder, including these traditional blowers.

Han

When I moved into this house, one of the first things I did was build this han with some scrap wood from the land. The han is a traditional Zen temple instrument, usually used to call folks to meditation or conclude a ceremony—it is struck with a wooden mallet in a rhythmic, roll-down fashion (like a bouncing ball). I was enchanted by the sound when I first heard it. I use my han to ground myself in the present moment (to wake up) and to wake up the spirits of the land—to announce myself to them and to call the willing into communion. Traditionally, there is a calligraphic inscription on a han. The han at the Zen monastery I visit a few times a year (Tassajara) is inscribed with these words: “Wake Up, Life is transient, Swiftly Passing, Be Aware, The great matter, Don’t waste time.” Instead of painting this on my han, I let the unwritten (and unwritable) Tao of the woodgrain convey its own message.

Wild Incense (in abalone shell, with abalone lighter)

When I am on the land in an intentional way, I gather sacred, medicinal, and fragrant plants to burn. I burn them at my altar, before ritual or significant events, and when I write, record, or perform music. I like to invite the spirits of these plants into my life and creative practice. I appreciate the way my awareness is subtly altered by their unique personalities, oils, and alkaloids. And each plant carries some essence or memory of the place where they grew. The burning and the gathering of incense is a vital part of my animistic spiritual practice. In this shell (which I also gathered) are mugwort, cedar, sage, and Santa Lucia fir sap—all from Big Sur—osha root from Mount Shasta, western juniper from the Sierras, and common juniper from the Norwegian Arctic. The abalone lighter cover was a gift from my wife—one of the best I’ve ever received.

Pelican Skull

Some years ago, I was backpacking alone in the Big Sur backcountry on an overgrown trail and stumbled upon a neat pile of bloody feathers. It was the unmistakable kill of a cat (feathers chewed off, as opposed to plucked, and piled up tidily), but they were oddly large feathers—more than six inches long—and plain brown, not resembling any of the bigger birds that live in these mountains. Poking around a little, I found the signs of a “drag” (pretty much just what it sounds like: the trail a predator leaves when they drag their prey for a short distance). At the end of the drag was a hollowed-out rib cage, two enormous untouched wings, and the severed head of a brown pelican—snipped off by a mountain lion (their tracks were everywhere). I can only assume the pelican was blown off course, or unwell and disoriented, but somehow he ended up quite far from the ocean and in unlucky proximity to a (likely) bemused, yet delighted, lion. It was all too strange and wonderful not to strap that stinking pelican head to my backpack and hike it home. Later, I wrapped it in chicken wire and left it outside for months, so the sun, ants, and other little critters could lend a hand and clean it up.

Melodeon

Over a century old, this melodeon—also called a pump organ—was crafted from Finnish birch on the British Isles, a convergence point for my ancestral lines. Its voice is rich and resonant, ranging from deep glacier-like rumbles to high, insect-like hums. A cornerstone instrument in my work since Cold Spring, I reach for it whenever a recording needs grounding—or a touch of the numinous. Originally designed to fold up for easy travel, this style of pump organ was marketed to Christian missionaries as a portable hymnal companion. It has been de- and re-sanctified as a thoroughly Pagan instrument, weaving hymns of Earthly enchantment. The bellows are patched with duct tape, the hinges creak mercilessly, and I’ve stitched up the straps that attach the pedals a dozen times (they’ve torn a couple of times during performances). This was an insane eBay score from a guy who didn’t know if it even played. It arrived in a used snowboard box with no padding—and played faultlessly and in tune. I’m certain we were destined to be together.

Hyperlite Mountain Gear 55 Liter Backpack

I’ve carried this ultralight backpack for about fifteen years—over the Kumano Kodo in Japan, through the Norwegian Arctic, in the High Sierra, and across many hundreds of miles of the Big Sur backcountry. It’s the smaller of my three packs, reserved these days for personal pilgrimages. Just big enough for several days of food, sleeping bag & pad, and a scrap of tarp (I truly hate tents and prefer to sleep out “coyote style”). At this point, this backpack feels as much like home to me as my cabin. I spend about one-eighth of my life in the wild, living from this pack, carrying only what I need to survive for a week at a time. It’s weathered, torn, and stained. It reminds me how little I actually need, and how fundamentally I belong on this Earth. My aim, both personally and in all my work, is to cultivate intimacy and reciprocity with the more-than-human world, and to guide others on these same enchanted, animistic trails toward kinship. This pack has been a steadfast companion on that path.

Heirloom Glass Amanita Ornament

This delicate glass mushroom ornament belonged to my maternal grandmother. It’s modeled on Amanita muscaria—the red-capped, white-spotted toadstool of old fairy tales. Each year, I hang it with care near the Winter Solstice, as the wheel turns and we tip—slowly—out of the dark. In Scandinavian traditions, Amanita muscaria holds mythic weight. They were (and are) consumed by Sámi reindeer herders and shamans courting visions during the long Arctic nights. Some folklorists trace elements of the modern Santa Claus—his red suit, flying reindeer, and chimney entrances—to these mushroom rites. I’m not big on Christmas, but Jul (from which we get “Yule”) meant wheel, and it was a time to mark the turning, to gather close, and to remember the old ones who faced the long, cold, dark months with no way out but through. It’s a time of year I like to honor my ancestors for their courage, kinship, and inner fire. This ornament, for all its fragility, carries a little of that fire—a spark from my grandmother, from older winters, and from Earth-reverent rites half-remembered.

Rejection Letter from Gary Snyder

This framed rejection letter from Gary Snyder is certainly one of my most treasured objects. I wrote to Gary—poet laureate of the wild—to invite him to record an album of poetry for Gnome Life. He declined, graciously and with warmth, stating simply that: “Life is too short to take on new projects though – I am already well-engaged.” Though I’ve only met him once (my hands and voice shaking at a book signing), Snyder has been one of my most faithful guides. His writings—The Practice of the Wild, Old Ways, Rip Rap—invited me into a world of essays and poems that were alive in relationship to the land and rooted in physical practice. His insistence that we become “native to our place” changed the course of my life—drawing me away from urbanity and into a pursuit of belonging to landscape. I live where I live because of his words. I do the work I do because he showed me that the wild, artistic practice, and spiritual life are not separate paths but one long, weird, mysterious trail. I keep the letter just beside my recording setup—a totemic object, touched by the hand of one of my most venerated creative ancestors.

Ponderosa Pine Tree

Just beyond the fence of my cabin stands a great ponderosa pine tree. He’s (he feels quite male to me) been growing in that spot for about 300 years. This property, which sits high on the western slope of the Santa Lucia Mountains, rests in an ecotone—or a site of overlapping ecological niches—so almost every tree native to Big Sur is present on the land and visible from my bedroom window. We have redwoods, cedars, madrones, tan oaks, coast live oaks, bay laurels, sycamores, big leaf maples, and ponderosa pines for neighbors. I love them all. But this pine in particular is an important companion to me. He stands directly in front of my bed and looms above me in my outdoor bathtub—where I do a lot of my writing. Pine song (wind through pine boughs) is my favorite sound—it erases my disparate thoughts like nothing else and grounds me in this enchanted, numinous wild world. With his numberless, broad branches, this ancient ponderosa generously fills my life with pine-song.

Kin (August 15th, 2025) Gnome Life Records

Live Dates

8/15/25 – Los Angles – The Philosophical Research Society – 7:30pm

8/16/25 – Berkeley – the Alembic – 6:30pm

8/17/25 – Big Sur – the Grange Hall – 7:00pm

Online Listening Party

On Saturday, August 9th at 12pm (PDT), there will also be an online listening party through Bandcamp. Details can be found here: https://gnomelife.bandcamp.com/merch/fletcher-tuckers-kin-listening-party