Best known for his loosely conceptual 1972 psychedelic folk classic Dreaming with Alice, Normandy-based English singer-songwriter and painter Mark Fry is our latest ‘Off the Shelf’ guest. In this series, we ask artists to present objects from a shelf or shelves in their homes and discuss them, a form of storytelling through objects.

Mark Fry recently released a new album, ‘Not on the Radar’, via Second Language (order it here). Produced by David Sheppard (Snow Palms, Ellis Island Sound), the album was primarily recorded live with his band—guitarist Iain Ross, double bassist John Parker, keyboardist/vocalist Angèle David-Guillou, and percussionist Sheppard—in Fry’s painting studio. This approach aimed for a “spontaneous creative experience,” reminiscent of classic albums like The Band’s ‘Music from Big Pink.’ The album’s title reflects Fry’s rural isolation and a deliberate “existential disconnection from the entrapments of modern life,” which allowed him to find the solitude necessary for his songwriting.

Album highlights include the aching nocturne ‘Daybreak’, watch the accompanying video below, created by Howard Holloway.

The songs that make up Not on the Radar are among his finest, and are lifted by beautifully restrained, sympathetic ensemble playing, all while Fry’s remarkably preserved voice radiates new shades of delicacy and gravity.

His selections below capture that painter’s eye detail as he recalls distant memories with beautiful clarity and storytelling. It’s an excellent read.

Off the Shelf with Mark Fry

Etruscan man

At some point during my childhood, an Italian friend gave my father this little figure of an Etruscan man: he then gave it to a painter friend, and years later, the painter gave it to me. The day I collected it, my wife and I went for a Japanese meal in Soho. I had the Etruscan man in one of my jacket pockets and showed it to her, and told her the story. During lunch, I found myself chewing on a particularly resistant piece of gristle, which I carefully spat into a paper napkin and placed in the other pocket (I think I didn’t want to offend the cook). We then got the giggles, imagining if I were to be run over by a bus what people might conclude from what they found in my pockets.

Ouagadougou bicycles

In February 2001, we went to FESPACO, the Pan-African film festival, which that year was held in Ouagadougou in Burkina Faso. In the 1960s, West African film students went to train in Paris and Moscow, whose cinema schools produced influential filmmakers, including Souleymane Cissé and Ousmane Sembène. We saw wonderful films that stood little chance of being seen outside Africa owing to lack of interest from international distributors. During the festival, people from many neighbouring countries, including Mali, Mauretania and Niger, would make their way to Ouagadougou’s main market. I noticed a young boy selling little bicycles, which he had made from wire. I bought two from him.

Lupo

In the early 1960s, my parents bought a small plot of land on the Monte Argentario, on the Italian coast north of Rome, from a chicken farmer who built them a little house overlooking the sea. The farmer and his family had a dog called Lupo. He was meant to be a guard dog and was often chained to a tree in the hope he might appear fiercer. He lived mostly on bits of leftover chicken. The farmer let him off his chain when we arrived for the summer holidays, as he knew how fond of Lupo my sister and I were. Lupo would follow us around and join in with all our games, and we treated him to bowls of spaghetti. Lupo was in love with a pedigree Maremma sheepdog called Nubia, who belonged to some friends of ours across the valley. He was always trying to get his leg over Nubia, but she wasn’t having any of it, perhaps because he was just a mongrel farm dog. One summer, we arrived to find that Lupo wasn’t there. The farmer said that he had done a “Don Giovanni”. He had gone for a walk up the hill and didn’t come back. The summers were never quite the same without him.

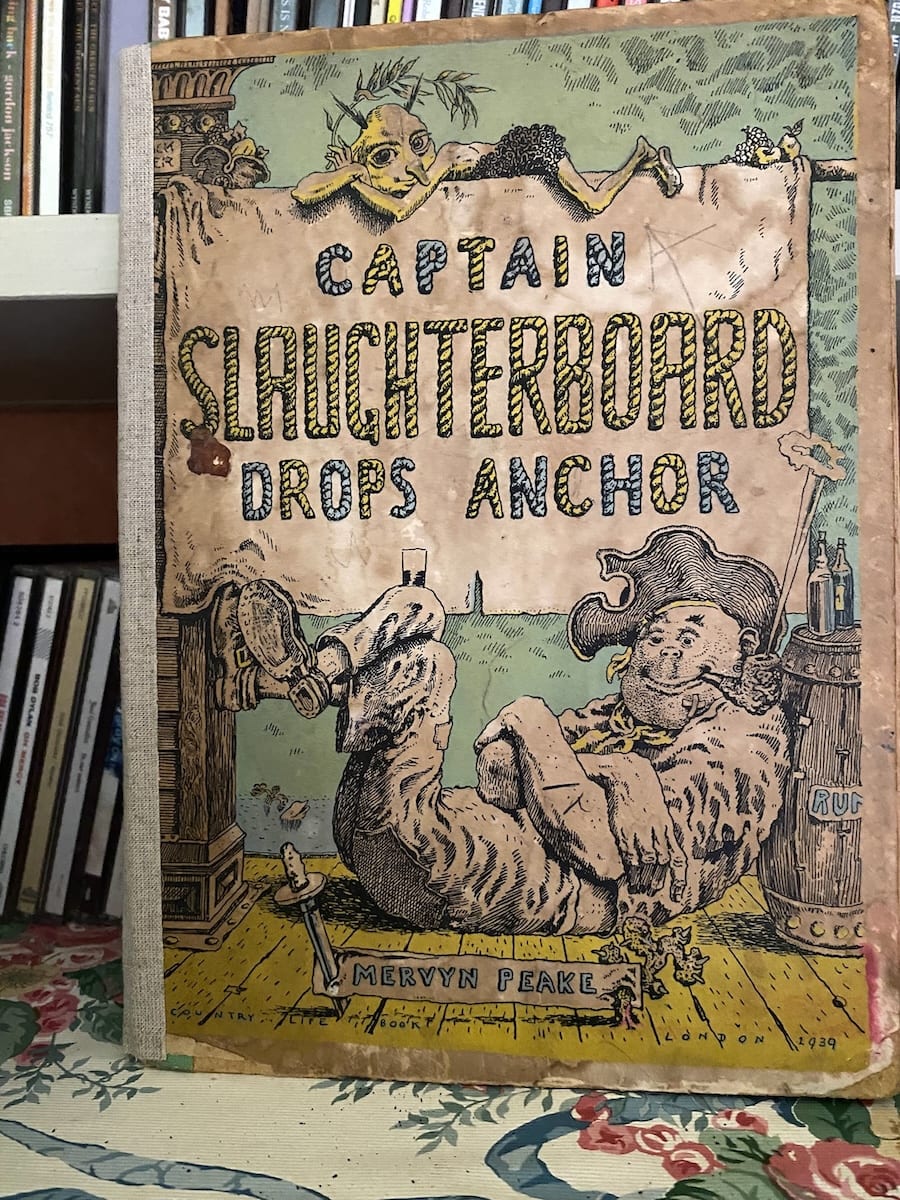

Captain Slaughterboard Drops Anchor

This was my favourite book when I was a small boy. It was always a thrilling and slightly terrifying experience sailing on The Black Tiger with Captain Slaughterboard and his motley crew. There was Billy Bottle the bos’n, whose arms were so long he could tap out his pipe without bending his knees; Jonas Joints the first mate, who could do handstands in the rigging while balancing bottles of beer on the soles of his feet; Peter Poop, The Black Tiger’s cook, who had a cork for a nose; and Charlie Choke, who was covered in “dreadful drawings in blue ink”. But the most haunting character was the sly and dangerous Captain Slaughterboard, always growling at his sailors that he would use his very large cutlass to “chop them up like mincemeat” if they didn’t behave. After many adventures, the Captain ends up on a magical island where he falls in love with The Yellow Creature, and they spend their days catching “strange glittering fish”.

My mother’s painting of the fort at Ansedonia

In the late 1950s, my parents rented the house of a friend above the old Italian town of Ansedonia, from where you could just make out the veiled mountain of the Argentario, where my parents would eventually build their own house. Their friend was an explorer and conservationist who had spent many months riding elephants through the jungles of India in search of the elusive tiger. He knew a lot about the history of Ansedonia, which in ancient times had been an Etruscan settlement. One day, he said he wanted to show me an underground cave that you could only swim into. This sounded like an adventure not to be missed. We swam for maybe half an hour around the Ansedonia headland until he pointed to a luminous pool of deep blue, ultramarine water beneath our treadwatering feet. “Now hold your breath and follow me,” he said. We dived down with our masks and snorkels and swam through a secret arch of seaweed before surfacing into a vast underwater cave. One day, I will try to find it again.

My old Landola guitar

In 1980 I travelled to Mali in West Africa to visit a friend who was working as an agronomist in the Inner Niger delta. I took this guitar with me. The delta is a wild and remote part of Mali, flooded half of the year and only accessible by canoe. We travelled around the delta for six months, visiting little fishing villages and finally making our way up to Tombouctou. Because I had my guitar with me, I was treated as a wandering griot and was commanded to play by different village chiefs. One day, we came across a group of nomadic Tuareg who were camped by the river waiting for the rains to come before continuing on their migratory route. The king of this group of Tuareg was called Hodda. He wanted to hear the white griot play. An evening was arranged for the following week. We left the little fishing village where we were staying and some hours later, guided by the moonlight, found the Tuareg camped a little further downriver. Hodda was waiting for us and had laid out a big rug and a kerosene lamp in front of his tent. He was surrounded by all his wives and children and many armed Tuareg, swords and rifles at the ready. I played until there were only three strings left on my guitar and blood on my fingers. They particularly liked my rendition of Johnny B. Goode.

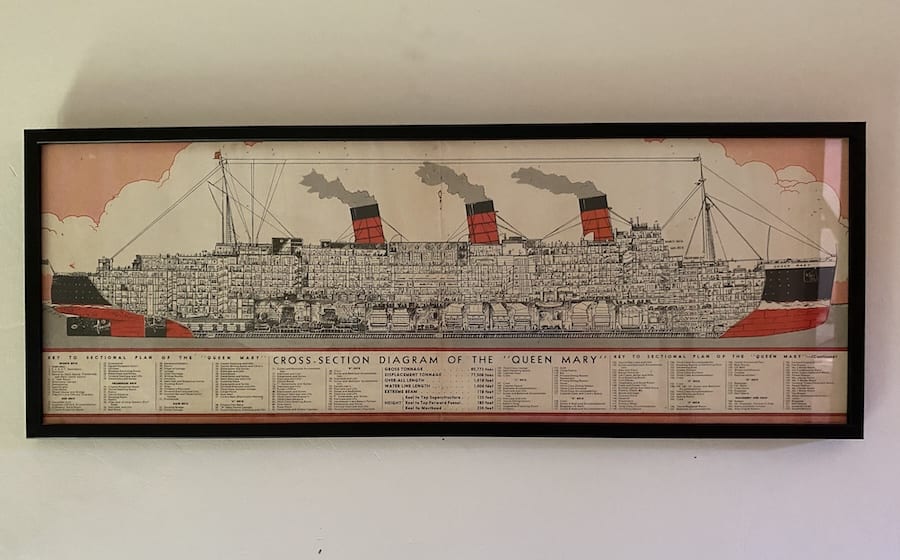

The cross-section of the Queen Mary

In 1960, my father won a Harkness Fellowship for painting, which meant travelling to the US with his young family and spending nearly two years there to study and paint. We sailed to New York on the Queen Mary. We boarded the ship at Southampton. She seemed to go on for miles and miles along the quay. Eventually, we found our designated gangplank and boarded the gigantic ship. We were in steerage. I remember a hot and windowless cabin somewhere near the engine room. The crossing took five days, and on the last day, our parents woke my sister and I at dawn and said we had to quickly come up on deck; we were going to see something we’d never forget. We stood shivering in the freezing first light, wondering what the surprise was going to be. Suddenly, out of the early morning mist, there appeared the Statue of Liberty.

The trombone

I can’t play it, and I don’t think it even works. I bought it from the auction rooms in Islington years ago. It reminds me of the moment I felt the first seed of wanting to be a musician being sown. I was standing in a corridor at school, my ear pressed to the door of one of the music rehearsal rooms. One of the pupils was practicing the French horn. I knew that this boy had recently lost his father in a tragic gliding accident, and it seemed to me the sound of his horn was speaking to the sadness he was feeling, and I realised then that a musical instrument could also be a close friend with whom you could share your innermost feelings, and with whom you could escape.

My father’s easel

My father used to make his own easels, but this one he bought, and now it lives in my studio. My parents were both painters. Easels, the smell of turpentine, linseed oil and paint were the backdrop to my childhood. I suppose they are my madeleines.

A child’s abacus

I found this at a car boot sale in Normandy, and it became a source of inspiration for my paintings. There is something mysterious and magical about an abacus. This one isn’t strictly a calculation tool. We discovered that it was designed by two Swiss teachers to help very young children explore the possibilities of counting. Somehow, it found its way from Switzerland to Normandy, losing a few balls along the way. I think it’s a sculpture in its own right; it reminds me of Alexander Calder.

Order Not On The Radar via Bandcamp: https://markfry.bandcamp.com/album/not-on-the-radar

Website: https://www.markfry.co.uk/