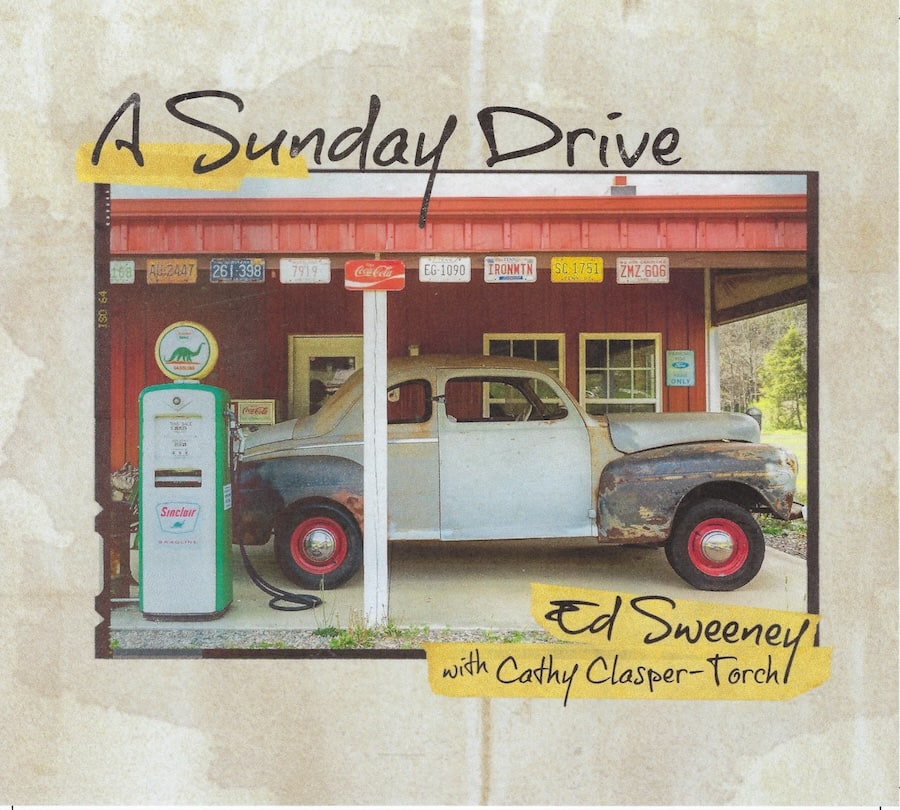

A Sunday Drive is inspired by the cover photograph taken by Cindy Wilson of an old car sitting in front of a gas station where everything had been abandoned for years, with one of the pumps listings fuel at 0.32 cents a gallon, a marker of what life used to be away from the main highways. As such, a collaboration with Rhode Island violinist Cathy Clasper-Torch, Ed Sweeney describes the album, a mix of traditionals and covers, as a collection of such markers, capturing the variety of music heard over the car radio, at a farmer’s market, or sung or played from a front porch.

Appropriately then, it opens with a fiddle-led instrumental uptempo reading of Auld Lang Syne, followed by, with Sweeney on plucked banjo, the traditional A Long Time Traveling, learnt from the playing of old-time Appalachian banjoist Frank Profitt, a key figure in the 60s and 70s, a hymn more often known as White in tribute to Benjamin Franklin White, compiler of The Sacred Harp.

Up next is the circling picked and strummed Right Foot Out, written in 1986 by Stephen Snyder, a folk-blues number about always moving forward, returning them to traditional pastures with a suitably spooked take on the cowboy classic Bury Me Not On The Lone Prairie in honour of the many unmarked graves, the instrumentation of traditional fretless banjo, Chinese erhu and, played by Daryl Black Eagles Jamieson, Algonquin Drum and Rattle to represent the many different cultures that met their end on the prairie. There’s a highly effective black-and-white video of it below.

Given the other tracks and context, it’s a surprise to find an acoustic guitar and mournful violin instrumental arrangement of George Harrison’s While My Guitar Gently Weeps, though it sustains the air of loss beautifully. A further instrumental follows with the elegiac Lament For The Death Of The Reverend Archie Beaton, a traditional Irish air composed by the late John Mason, a native of Orkney and founder of The Scottish Fiddle Orchestra, in tribute to the minister of Dundonald Parish Church, Ayrshire, a champion of Gaelic culture, who died suddenly in 1971.

It’s back to Appalachian bluegrass banjo for the traditional Walking Boss, an African-American work song collected in 1906 about those in charge of labourers laying the railroad tracks. Sweeney learned it from the recordings of Clarence Ashley, a well-known folk singer and banjo player who also performed with Doc Watson and started his musical career as a medicine show performer in the early 1900s.

The only original number is another instrumental, A Little Traveling Music, a thrumming guitar and fiddle tune designed to evoke and accompany road trips down the backroads of America, while the last of the traditional tunes is When I Get Home, a returning to the source hymn written in the late 1800s by Austin Miles and recorded in 1958 by Elizabeth Cotten, from whom Sweeny learned the first verse, the second coming from a 1900s hymnal.

The final instrumental, A Childhood Medley, strikes a playful mood as, per the title, played on acoustic guitar, it stitches together Frère Jacques, The Mickey Mouse Club March and Grandfather’s Clock, ending with a faint chuckle.

The closing track carries a personal meaning, recalling how his mother emigrated to America from Ireland as a young woman in the late 1940s and clearly had restless feet, with Sweeney having lived in seven states by the time he was 15. The song, Distant Shore, written by Rhode Island musician Mary King, a frequent live performer with Sweeny and Clasper-Torch and herself of Irish immigrant descent, is about knowing what you’re leaving behind but resigned and committed to your new destination.

Unless you live in North America, particularly Rhode Island, the chances of experiencing Ed Sweeney and Clasper-Torch performing are remote. However, A Sunday Drive, a fine album in its musical and emotional simplicity, is ample compensation.

You may also like: