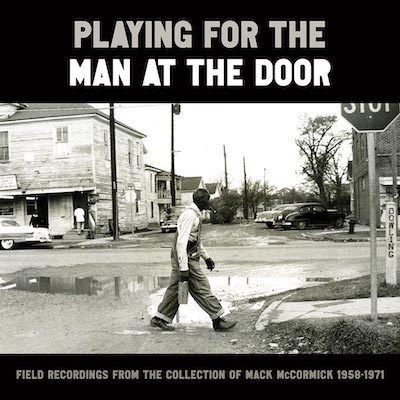

Playing for the Man at the Door

Field Recordings from the Collection of Mack McCormick, 1958–1971

Smithsonian Folk Ways

4 August 2023

In the film Blues Back Home, the Arkansas singer-guitarist CeDell Davis recalls house parties taking place on Saturday nights at Mississippi farms. People came from out of town to these gatherings, which might last until Sunday evening. There was bootleg whiskey and homebrew beer to purchase and dice games in the back room. Of course, there was music, often provided by the likes of Davis himself and Robert Nighthawk. Some guy with a pistol could be manning the front door. The police might come raiding as the farm’s lack of an alcohol license would be obvious. Davis would grab his stuff and leave though the police never arrested performing musicians. In later years, people left these farms, moved to the far-flung cities and took their music with them.

Perhaps the archivist Robert ‘Mack’ McCormick attended such house parties. Either way, between 1958-71, he captured African American musicians on tape in the region he dubbed ‘Greater Texas’, namely Western Louisiana, East Texas and sections of Oklahoma and Arkansas. His six hundred reels of sound now rest with the Smithsonian Folkways label, which has released sixty-six tracks via this engrossing collection. Some iconic names included will be familiar, but many more could stretch the knowledge of even ardent scholars.

This is music that reverberates from rocks to rivers, from great plains to piney woods. It’s the wild wolflike blues, red in tooth and clawhammer. Rawness and reality, without the spit and polish of record label recordings. Every song tells a story, but behind these lie the actual artists whose life stories are often absorbing. CeDell Davis himself is a fascination. Badly disabled in his teens from polio and left on crutches, he relearned the guitar left-handed, using a silver case knife for his slide. His recordings on this compilation include the lovelorn grit of Darlin’ (You Know I Love You), some tough boogie-woogie on It’s Alright, whilst his parched vocals crack on the heartbroken Rollin’ And Tumblin’. Davis would lay his knife flat across the frets or at an angle for certain notes. He claimed to be a true original, and no one should doubt it.

Then there’s Edwin ‘Buster’ Pickens, a veteran freight train-hopper and piano player in lumber camp barrelhouses. He sported a hair quiff to differentiate himself from the sawmill workforce. His droll vocals can be heard on Groceries On My Shelf with its lyrical piano ripples, and Shorty George, where achingly tender chords lament an eternal loser. We also get his bawdy take on The Ma Grinder, which the writer Elija Wald describes as one of Pickens’ ‘insult songs’. These were tunes popular with backcountry levee camp workers, well used to nights of prostitution and violence. Pickens once said, “The nach’al blues comes from personal experience.” He was murdered over a dollar debt in a barroom quarrel.

Another of the itinerant performers featured is Grey Ghost, who offers the cranky detuned piano and hobo vocals of One Room Country Shack. Like many others, his trade became obsolete in the jukebox era after World War II. Lightnin’ Hopkins does a live version of Mojo Hand with choppy thumb-picked guitar and his penchant for throwing in unexpected frills. He must’ve been a nightmare to play alongside. In this track, Hopkins buys himself a magic charm so his woman can have no other man.

Mance Lipscomb is another curiosity. He was influenced by his father, an Alabama enslaved person who played fiddle, but his mother’s mix of gospel and Choctaw cultures was also key. She was renowned for dancing with large baskets atop her head. A sharecropper and labourer, Lipscomb performs God Moves On The Water with a skiddy bottleneck feel to his fingerpicking. Tall Angel At The Bar has flamenco hints and dance-style pluckings, but it was Tom Moore’s Farm which made his name, as Lipscomb’s slippery fingerstyle underpins a tale of prison farm grievances. His spoken outro refers to dead men floating down the river and the dire risks of singing about cruel white bosses. In the book Juneteenth Texas, writer Francis Abernethy finds Chris Strachwitz and McCormick in search of the song’s origins. They went to Lipscomb’s home region of Navasota in Texas. Among those who recommended Lipscomb as a guitarist was the wretched prison farm owner Tom Moore himself.

Elsewhere, variety comes with Robert Shaw’s banging barrelhouse piano on The Clinton. Kid Wiggins gets contemplative at the keys for Sugar Blues, with Allen Van doing a pumping take on China Tea, a piece made popular by Russ Conway in 1959. Allen does the last half in New Orleans style with less movement in the left hand.

Dudley Alexander and Washboard Band give us St James Infirmary, a mix of rambling skiffle and zydeco done on creaky fiddle and wheezy accordion. The lyrical blend of French and English makes it hard to gauge much connection to Cab Calloway’s version. Galveston street entertainer George ‘Bongo Joe’ Coleman pounds his makeshift kit of oil drums on Put Your Money Where Your Mouth Is, a witty account of failed seduction. Also, listen out for some rapid patter from cattle ranch auctioneer Walter Britten, along with Murl ‘Doc’ Webster’s peppy pitch for his travelling medicine show.

Not many blues greats stayed in the Delta, where the genre’s genius was conceived. Those that did mostly remained cult figures, their ghosts waiting for a project like this to refresh their status. But thanks to them, the blues is still out there, still riding the rails and seeking new adventures.

Order Playing for the Man at The Door here