Robbie Robertson, Canadian lead guitarist and principal songwriter of The Band, has died at age 80. A statement issued by his manager said he died on Wednesday surrounded by his family after a long illness.

Robertson is credited with some of The Band’s most well-known songs, including, ‘The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down’, ‘Up on Cripple Creek’ and ‘The Weight’, which, while not a big hit, is one of those songs that seems to have endured across time.

My exposure to Robertson was through The Band and Bob Dylan rather than his solo material; with that in mind, below are just some personal highlights I wanted to share in tribute to Robbie Robertson.

The music that both he and his fellow bandmates created as The Band has been hugely influential, and they sounded pretty unlike any other band at the time. To place that in perspective, their solo debut 1968 roots rock album, Music From Big Pink, was released a year after The Beatles Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, followed by their self-titled solo (main image) the following year.

And as for legendary, what about that 1976 concert? Advertised as their ‘farewell concert’, it remains one of the most legendary concerts ever. Thanks to Martin Scorsese’s documentary ‘The Last Waltz’, released in 1978, the concert has been enjoyed by many since. It featured a staggering guest list that included Ronnie Hawkins and Bob Dylan, as well as Paul Butterfield, Bobby Charles, Eric Clapton, Neil Diamond, Emmylou Harris, Dr John, Joni Mitchell, Van Morrison, Ringo Starr, Muddy Waters, Ronnie Wood, and Neil Young. Robertson went on to produce many movie soundtracks for Martin Scorsese. He also continued to record as a solo artist, and on his most recent record, Sinematic (2019), he was joined by Van Morrison on the opening ‘I Heard You Paint Houses’.

Here’s a great clip from The Last Waltz in which The Staple Singers join The Band for The Weight, a personal favourite:

In his 2017 autobiography Testimony (highly recommended), Robbie Robertson was keen to emphasise storytelling’s importance to him, an essential tool of any songwriter. He wrote in the book’s opening:

I was introduced to serious storytelling at a young age, on the Six Nations Indian Reserve. The oral history, the legends, the fables, and the great holy mystery of life. My mother, who was Mohawk and Cayuga, was born and raised there. Whether it was traditional music, or story-songs like Lefty Frizzell’s “The Long Black Veil,” or sacred mythologies told to us by the elders, what I heard on the reserve had a powerful impact on me. At the age of nine I told my mother that I wanted to be a storyteller when I grew up. She smiled and said, “I think you will.” So these are my stories; this is my voice, my song— And this is what I remember.

In that autobiography, he doesn’t begin his tale with the typical backstory of his parents; instead, he begins in the spring of 1960 as a young sixteen-year-old travelling on a train from Toronto to Fayetteville, Arkansas – to the ‘holy land of rock n roll’ – to try and get a job playing for Ronnie Hawkins and his powerhouse band ‘the Hawks’. Later, Bob Dylan would catch the Hawks in a New Jersey club; impressed by Robertson and Levon Helm, he would invite them to join his new band (the entire band would later join Dylan). Making their debut in August 1965 at Forest Hills Stadium, Dylan was keen to build on his controversial electric set at Newport Folk Festival, and all Dylan fans know what happened next.

Dylan’s shift from acoustic to electric wasn’t made without issues, and while the now famous ‘Judas’ shout by UK student Keith Butler at Manchester Free Trade Hall during Dylan’s 1966 world tour became famous, it wasn’t an isolated reaction. In Nigel Williamson’s ‘The Rough Guide to Bob Dylan’, Robertson recalls: “My memory is that they were so angry, so upset, saying this is horrible and throwing junk and garbage at us. We had to stand there and let the stuff bounce off us…that happened all over the world.” In his autobiography, he provides greater insight and detail. The reception of their electric set differed across gigs, and not all were received so negatively as you might have thought. Some audiences booed but then got caught up in it all and stormed the stage in excitement by the end. While some adverse reactions were expected, none came as more of a shock than on their home turf of Toronto, where they also had a lousy reception; but thankfully, they remained resilient and thick-skinned – otherwise, we would have missed out on some music.

That mixed reception to Dylan going electric often overshadows some of the more interesting dynamics between The Band and Dylan. In Testimony, Robertson explains how they were still finding their feet during that extensive world tour, and that includes Dylan, who was not used to playing with a band. Many conversations about those challenges are recalled, and at one point, Robertson tells his fellow bandmates, “…we just gotta be on top of it and go with the flow”. There are plenty of great stories told around this time, including one involving Paul Butterfield (of Paul Butterfield Blues Band) and a bag of weed that he mistakenly thought The Band had stolen from him to more general and humourous observations such as Robertson’s amazement at how Dylan managed to remember all the lyrics to his songs which “seemed to contain more verses than the bible”.

Despite the backlash from the folkies over Dylan going electric, the sales of Dylan’s album, Highway 61 Revisited (1965), proved it was the right move, and even Phil Ochs called it “the most important and revolutionary album ever made”. As for Dylan and The Band finding their feet…that didn’t take long.

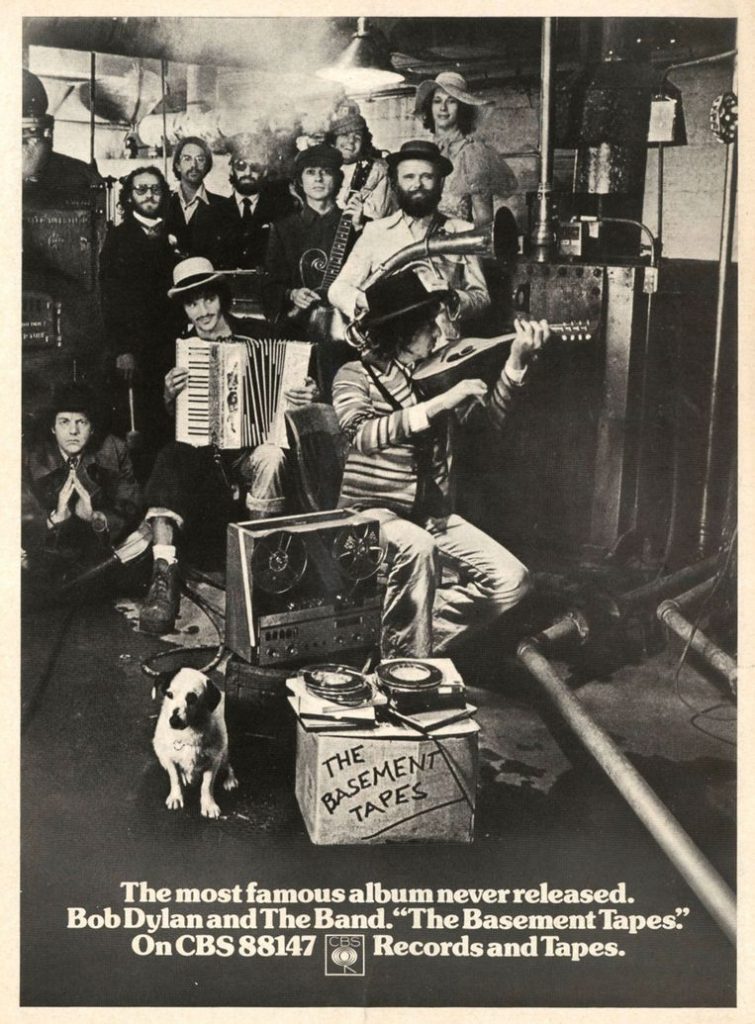

Among some of the most iconic Bob Dylan and The Band moments is the legendary The Basement Tapes, an album which wasn’t meant to see the light of day. Recorded after his world tour, between June–September 1967, in the cellar of the house called Big Pink, it wasn’t until much later that Dylan gave permission for an album which was eventually released in 1975. Robertson was tasked with selecting songs from the sessions and worked on them with engineer Rob Fraboni. Robertson was also responsible for the look of that iconic cover which was inspired by a 1967 Thelonious Monk album called Underground – the photo was taken by Reid Miles, and Robertson is posed in a Red Army uniform.

During the final week of 1971, The Band played four legendary concerts at New York City’s Academy Of Music, ushering in the New Year with electrifying performances, including new horn arrangements by Allen Toussaint and a surprise guest appearance by Bob Dylan for a New Year’s Eve encore. In 2013, Live At The Academy Of Music 1971 was released as a deluxe, 48-page hardbound book with previously unseen photos. In the Folk Radio review of the album, Helen Gregory shared:

The intention of this release, according to Robbie Robertson’s website, is to produce “a definitive document of the pioneering group’s stage prowess at the apex of their career” and, while debates may continue indefinitely over which was their “best” record, Rock of Ages and this reincarnation of it must surely rate consideration.

The onstage banter and song title announcements help to convey the atmosphere among the musicians. Robbie Robertson again: “It was the final night; there was a thrill in the air”, and that sense of a band firing on all cylinders – and *knowing* that they’re playing up a storm – really comes across. Garth Hudson’s keyboards are a particular revelation, and the tightness of the rhythm section (Rick Danko on bass and Levon Helm on drums) is a joy to hear in such detail. With the addition of a 5-part horn section (with charts written by Allen Toussaint) for the second half, the show kicks into overdrive, and it’s difficult not to get up and start jumping around. And, needless to say, when Bob Dylan joins The Band onstage for the four encores, the roar of the crowd makes the hairs on the back of your neck stand up: it must have been an electrifying experience.

I’ll leave you with this 1969 rendition of Highway 61 Revisited at the Isle of Wight Festival; they knock it out of the park:

Robbie Robertson: July 5, 1943 – August 9, 2023