Reg Meuross

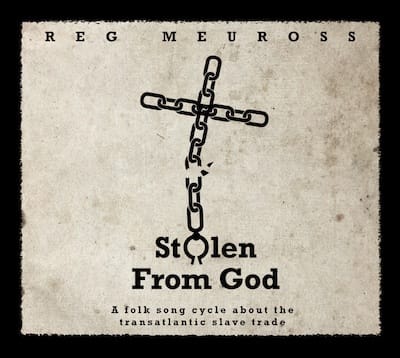

Stolen From God

Hatsongs

7 April 2023

In his 27 years as a solo artist, the Somerset-based singer-songwriter Reg Meuross has tackled a wide array of historically based subjects in songs exposing injustice and inequality or celebrating heroism and courage. He has written paeans to the NHS, Emily Dickinson, Victor Jara and Sophie Scholl, shed light on how miners were unjustly vilified as cowards when they were ordered to continue their work rather than serve during the war, turned a critical eye on contemporary England and told of the tragic fates of murdered or separated lovers and of the ignominy heaped upon unmarried mothers and prostitutes even after death.

But in Stolen From God, he has unquestionably written his masterpiece in a song cycle that turns an unflinching eye on the toxic legacy of the transatlantic slave trade, especially in his home in the South West of England. Shocked by his realisation of his ignorance of British Black History, of the Empire and how so many of the nation’s grand estates and lauded figures were tainted by the stain of slavery that had served as the foundation for their wealth and public acclaim.

Embarking on four years of in-depth research into family trees, church records, and oral histories passed down through generations and uncovering many uncomfortable long-hidden truths in the true tradition of folk music, he has turned these into songs about seafaring, war, class, politics and social history with subjects that range from how naval legends like Sir Francis Drake and John Hawkins who helped to establish the transatlantic slave trade, how it underpinned the British economy of the17th century, the first petition to abolish slavery that originated in Bridgwater and Edward Colston, the Bristol merchant, entrepreneur and philanthropist finally revealed as being involved in the forcible kidnapping and transportation of some eighty thousand Africans.

The album variously features contributions from Jali Fily Cisshokho, Cohen Braithwaite-Kilcoyne, percussionist Roy Dodds and Jaz Gayle and Katie Whitehouse on backing; it sets sail with the concertina and strummed guitar The Jesus of Lubeck, related in the voice of a crew member who sailed with John Hawkins, a Tavistock naval commander who, in 1562, determined to break into the Portuguese-controlled slave trade left Plymouth for Sierra Leone and helped to establish The Transatlantic Slave Trade. Despite publically denouncing the kidnapping of Africans, Queen Elizabeth awarded him his coat of arms, which included a chained and bound enslaved black African, and provided him with the titular ship for his next voyage. Hawkins was a good friend of Francis Drake, who, history neglects to tell us, was a fellow slave trader.

With a kora intro, taking its cue from a lecture tour by slave turned abolitionist Frederick Douglas regarding Christian hypocrisy, the slow swaying The Way of Cain declares that “You can chain a man like an animal but you can’t put the iron on his soul/So the fear of the Lord and the lash and the sword/Must turn him around to your goal”, specifically referencing slavery in America with the line “To work a man like John Henry takes a heart as hard as steel”.

Concertina again setting the jaunty rhythm, with Braithwaite-Kilcoyne also on lead vocals, noting the prevalence in the West Country, England No More notes how the slave trade wasn’t confined to Africans, with the notorious press gangs kidnapping the destitute, the homeless, prisoners, gypsies and children and, with the full support of a royal decree, trading them as indentured servants in the colonies, the song noting the irony of how “We who took the African and sold to the American/We’re tasting our own medicine of poison slavery”.

Bristol was a particular centre of the slave trade, with many of its residents doing extremely well from it, perhaps none more so than the subject of the walking rhythm Good Morning Mr Colston, the Bristol philanthropist Sir Edward Colston whose wealth was earned at the auction block (it’s estimated he was directly involved in the transportation of at least eighty thousand enslaved people), the song sung in the voice of one of his ‘goods’ (“Good morning Mr Colston bless your generosity/It’s thanks to you there’s hospitals and poor-folk property/It’s thanks to you a hundred thousand souls were sold as slaves/And a quarter died in transit and the ocean was their graves/Good morning Mr Colston when will your soul be saved?”).

Again opening with kora and featuring flugelhorn, The Breath Of England is a quintessential Meuross melody, part shanty, part country, sung in the persona of James Somerset(t), a West African enslaved when he was eight and sold in Virginia to Scottish merchant Charles Stewart who then took him to England in 1769 (“to work on the factory line/The food I ate was dirty and I never got no pay”) where he was baptised, refused to serve Stewart longer and was kidnapped in 1771, taken to Jamaica and sold, resulting in his godparents bringing a case of Habeas corpus case represented by William “Bull” Davy that confirmed slavery was not legal in England and Wales (“the judge said just let justice be whatever the consequence/To breathe the air of England at first you must be free”).

Conjuring hymnal qualities, the fingerpicked title track is another swaying melody in its indictment of slavery as a crime against God (“God made these hands to pray and to praise…All the believers that you have betrayed/Your debt to humanity must be repaid/This is your legacy written in blood everything stolen from God”). Adopting similar instrumentation, Stole Away draws on the account of one Olaudah Equiano, a formerly enslaved person who settled in London and became a leading activist in the abolition movement, describing his capture and transportation (“They packed us in so tightly in the darkness and our dirt/The crying of my sisters – brothers dying from the hurt/The ship pulled into Bridge Town where they brought us up on deck/Chained together by our hands and feet or shackled by the neck/We feared we might be eaten by these wicked ugly men./As they pinched our skin and studied us”).

With 60s folk blues hints, I Bought Myself An African (“the day went on and by the end I’d bought 200 women folk and girls and boys and men/The captain said ‘These bodies that you see/Think on them as chattels like some cheap commodities’/And I bought another Africans three”) has Meuross in the character of a Bristolian looking to build his wealth while Senegalese kora player Cissokho provides the background voice of Goree, one of the enslaved.

Things return home for the shuffling, rhythmically choppy Bridgewater, which, like in the Johnny Cash song, has a man going around taking names, except here Reverend Chubb, Mr Tuckett and Mr White are gathering support for the first petition against slavery, and the release of those so held, though, inevitably conscience and commercial interest do not make good bedfellows (“The Lords say on the table let it lay/There’s far too much at stake to rule today/Almost every fortune made has been built upon the trade/And we need to get our compensation pay”).

Kora returns to introduce and colour the final track, the jogging fingerpicked, Guthrie-styled Stranger in a Strange Land, drawing on how, in 1772, the British army offered freedom to enslaved people who would enlist to fight against the American rebels. The song is told in the persona of Pierre Courpon, aka Peter the Black, the servant of General Rochambeau, a French officer who came to Devon, who married local girl Susanna Parker, and while the song has him remarking, “guess I’ll be buried in this town” apparently returned to France with his master, family remaining with descendants recorded in the Devon registers. Sung in the voices of both those outraged by slavery and those enslaved, this is not only a musical and lyrical triumph but, alongside Angeline Morrison’s The Sorrow Songs, one of the most important albums of the 21st century in shedding light on how, for centuries, we shut our eyes to the fact that the foundations of who we are as a nation were built on the broken backs and chains of others.

Touring begins with April launches at Bristol Folk House, Green Note London and Dartington’s Great Hall and will encompass Sidmouth Folk Festival, Whitby Folk Week and Costa Del Folk festivals with a particular focus on Black History month in October. Reg will be joined by Cohen Braithwaite-Kilcoyne (who plays on the album) and kora master Suntou Susso.

Details can be found here: http://www.regmeuross.com/events/