Milkweed’s ‘The Mound People’ is like a reconstituted form of folk music that feels as if it were created with alien technology and then left in a burial mound of its own for a few hundred years. Folk music has always been inextricably tied up with history, but rarely has the relationship been as mysterious and rewarding as it is here.

An air of deliberate and delicious inscrutability surrounds Milkweed. They describe themselves as ‘slacker trad’, and although a distinct DIY aesthetic is always present, this doesn’t quite do justice to the sheer strangeness of their music. European and American folk traditions appear side by side but in surprising juxtapositions, so that their songs often feel like psychic transatlantic collaborations gone slightly awry or haunted artefacts of unknown provenance. Their choice of material is willfully, admirably outré: their 2021 Christmas EP included songs from the Basque tradition and a cover of a half-remembered, unrecorded song by a band that no longer exists.

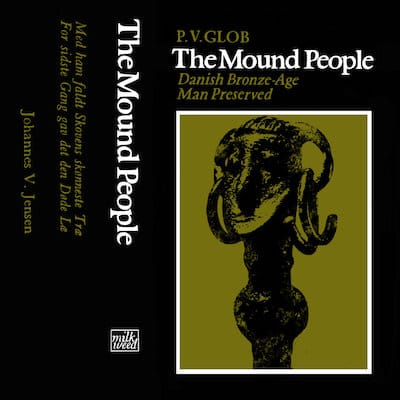

The Mound People sees the Milkweed myth grow even weirder and more alluring. There are eight short songs, conceptually linked by a 1974 text on preserved bronze age human remains by Danish archaeologist Peter Glob (who became famous in academia after his investigation of the Tollund Man). The band were sent the text by Minnesota-based shipwright and artist Justin RM Anderson, who rightly suspected that it might prove inspirational.

Of course, folk music has always been inextricably tied up with history, but rarely has the relationship been as mysterious and rewarding as it is here. The lyrics consist of lists of objects found in Danish burial mounds. These objects, whose context has deserted them over millennia, become strange, stark echoes of the past: when the music falls away in Eelgrass, the opening track, we are left with the words ‘horse head handle razor’ floating in space. Is it an incantation, a lament, or something else entirely?

The music is, if anything, even more disorienting than the words. Many of the tropes of traditional music are present, but it is as if they have been mistranslated or misremembered. The band used a 404 sampler to record everything here, and the result is a chopped, blended, reconstituted form of folk music that feels as if it were created with alien technology and then left in a burial mound of its own for a few hundred years. Eelgrass is full of eerie gaps and unexpected pauses, while the garbled voices in The Sorceress seem like a language degraded into its primaeval form. Weasel Bones has a cold, static-laden percussive crunch that underpins a Jean Ritchie-esque vocal; it begins as the most structurally conventional piece on the entire release (and at just over two minutes, is the longest) but then cuts out before it can reach any kind of melodic resolution.

These apparent acts of musical self-sabotage are actually highly effective, if disconcerting, ways to engage the listener. They build up a sense of uncertainty: are these songs in a conventional sense, or found objects, or some kind of elaborate hoax? Even a fragment of less than a minute can have a split personality, like the screech of distortion that offsets the jangling stings of Maggot Skins or Mountain Cranberries, which seems to sit somewhere between Asian and Appalachian traditions, each fighting to be heard among the omnipresent crackle and hiss. Perhaps most haunting of all is Bronze Sword – just a voice made to sound ancient and decomposed through the intervention of the 404, a technological gadget less than a quarter of a century old.

There are moments of strange and unexpected beauty scattered throughout The Mound People, not least on the lysergic Stallion Fights and the bewildering, dreamlike loops of closer Blackbird’s Nest. The singing is stunning throughout, and the poignant melodies percolate through each song, coming to the surface at unexpected junctures. It’s hard to find tangible reference points for music this different, and this interesting. Perhaps if Hedy West, the Moldy Peaches and Broadcast happened to meet at a Julian Cope convention, something like this might have been the result, or perhaps we have to look to literature or film for closer antecedents – the books of Alan Garner or the television of Nigel Kneale. But more than anything else, The Mound People is a uniquely eerie musical experience, a distorted vision of a half-hidden past.

Milkweed also feature on our Folk Show – Episode 130: