Lankum have never shied away from difficult themes, and their attitude towards traditional music has always favoured experimentalism over conservatism. They are one of a very small handful of groups (Stick In The Wheel being the other notable example) who not only seek to constantly evolve their own music but, in doing so, change the way folk music is recorded and listened to. It’s a truism to say that folk music is mutable and endlessly malleable, but for it to be so, someone has to have the courage to push it into genuinely new and exciting directions. False Lankum is the Dublin group’s fourth album as a quartet and their most uncompromising to date. It is not so much a retreat down the rabbit hole as a bold statement of intent and an example of how new ideas can still enliven old forms.

Lankum’s magic lies in the way that they are able to carry off these experiments while retaining the pulsating, punkish and frequently thrilling energy of a brilliant live band. Comparisons to The Pogues will persist and are valid up to a point, but closer reference points now seem to be post-rock and the noisier end of shoegaze, while the band’s continued use of heavy drones aligns them with experimental contemporary composers. What’s important is not so much that this is a wholly new combination of influences but that Lankum are able to bring them together with such aplomb. It all feels entirely natural.

It begins with disarming simplicity: Radie Peat’s unaccompanied vocal takes up the first sixty seconds of Go Dig My Grave, and you get the impression that the album could potentially go off in any direction. But with the addition of instruments – minimal at first, but slowly coiling and building – the intensity ratchets up. The discordant drone that drops about halfway through the song is where the band really nail their colours to the mast. Layers of sound – screeches, plucks, and percussive thumps – build upon each other as the song moves away from its melodic beginnings and focuses in on a very deliberate, very dark mood. Ian Lynch, who plays uilleann pipes, whistles and various other instruments, explored these techniques on his recent solo album. Here, with a full band, they are perfected: the framing device of a traditional song allows them to exist within – and to disrupt – the conventional narratives of folk music. The result is a profound, all-encompassing and ultimately compassionate exploration of grief.

A similar thing happens on Clear Away In The Morning, albeit with different techniques. The song begins with an atonal chirrup which blurs the boundaries between organic and synthetic before a more traditional thrum of guitar strings anchors the song in calmer waters, and a beautiful harmony keeps everything afloat. These maritime metaphors are not accidental – the whole album resonates with the hum and movement of the sea: the deep drones and high squalls, the dirty winds and clear skies. False Lankum’s involvement with the sea may be accidental – the band didn’t realise until after recording that every song contained a maritime reference of some sort – but it feels absolutely right, almost fated. It’s as if the band use the sea in the same way that Brian Eno might use a car park or an office block, or a shopping centre.

Lankum are masters at twisting a song at a certain point and taking it into unexplored corners. The New York Trader begins as a punkish acoustic chant before turning the noise up to eleven and tapping into heavy gothic-industrial energy, and then escaping its own confines with a brisk, confident fiddle tune. By contrast, the slow, winding On A Monday Morning has an almost imperceptible build, a musical landscape that swells, chimes and dies.

Throughout the album, moods are invoked with subtlety and ambivalence. Master Crowley is a reel pitched somewhere between jaunty and menacing, with its darker side being teased out as the song descends into hard squeals and ferrous clangs. Generally speaking, the songs with Peat on lead vocals are lighter in tone and more hopeful. Her singing on Newcastle is deceptive in its apparent simplicity and full of longing. Despite the sadness of the words, there is a defiant sense of positivity in Peat’s rendering. On the lengthy and tragic ballad Lord Abore and Mary Flynn, Peat’s voice joins Cormac Dermody’s, lending emotional heft to a stripped-back arrangement. The band’s characteristically weighty sound creeps slowly in over the course of the song: set against the comparative sweetness of the melody, it creates a delicate tension.

The emergence of Dermody as a singer is one of False Lankum’s most pleasant surprises. Equally impressive is the songwriting of Daragh Lynch, who provides the album’s two original tracks. Netta Perseus is gentle, beguiling and full of lyrical mystery. Like everything Lankum do, though, it is laced with darkness and, halfway through, switches from a lucid acoustic strum to a thick instrumental soup, as if a sudden madness had come across the narrator. Daragh’s other composition, The Turn, provides the False Lankum’s extraordinary final thirteen minutes. It is structured like a kind of progressive metal opus, full of unexpected turns but always revolving around a consistent and compelling message until the song finally breaks down into darkness and apocalyptic discordance.

Sprinkled throughout the album are three short fugues that act like the chapter breaks in a Godard film. They are not meant as palate cleansers in the way that interludes often are; instead, they are like little musical puzzles, ways to engage the listener more actively with the way the sounds are being created. In a way, they hold the key to Lankum’s highly individual approach to music-making: a discourse between band and listener that is challenging, raw, brutally honest and always rewarding.

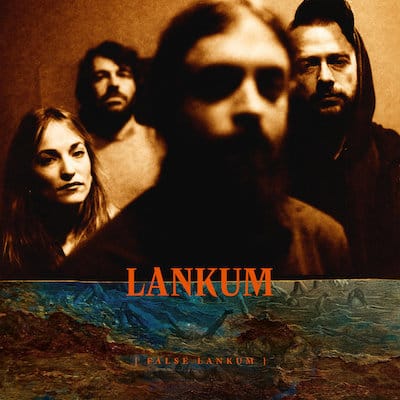

Pre-order/Save False Lankum