Almost a Sunset draws on traditional roots, refracted through a contemporary lens; this is not so much a sunset as the dawn of a glorious new chapter in Kathryn Roberts & Sean Lakeman’s increasingly illustrious career.

It has been a long five years since Kathryn Roberts & Sean Lakeman‘s last studio album (Personae). This month, the Dartmoor duo return in punchy form for their seventh ‘Almost A Sunset‘.

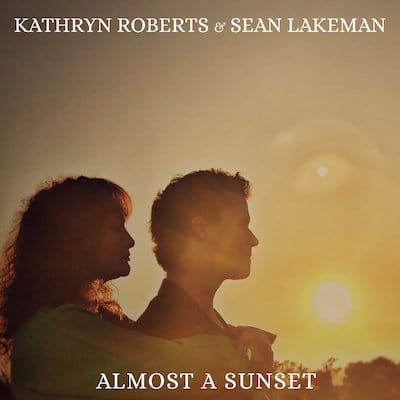

All but three numbers on Almost a Sunset are self-penned with Kathryn Roberts on vocals, piano and woodwind and Sean Lakeman on guitar, bass and percussion. They’re also joined by teenage daughter Poppy (her twin Lily provided the cover photography) on backing vocals for the album opener, Eavesdropper, dedicated to “gargoyles and eavesdroppers everywhere” that starts in a courtly-sounding manner before adopting a clopping rhythm. The song was inspired by the traditional folk song What Will Become of England, itself based on the alleged account of a paranoid Henry VIII installing gargoyles in the eaves (hence the term) of Hampton Court to listen in to the Hall. The song has nothing specifically to do with that but is instead a comment on political oppression (“Do as we say not as we do/We’re in charge of you they said”) and wealth-based social inequality (“Some have money and wish for more/They won’t lend a penny to the poor/They pass by with nothing but a frown/That’s the way the working person/Has been cast down on their knees/Punished by liars and thieves/Conmen who do as they please”) that has persisted throughout history (“Nothing changes we’ve seen it all before”).

Named for and about Kathryn Roberts’ favourite Dartmoor tor, the lilting piano-based Pew Tor begins and ends with birdsong as she sings of the contemplative silence experienced there, bringing comfort in loss and the notion of returning to the elements from whence we came (“And in that moment I felt you there/It was louder than our words ever were…I often wonder where you ended up/If you settled on my skin/If you ever became part of me/And if I breathed you in…swirling in your own galaxy/Drifting on the wind”) where “Life is but vapour and bodies just clay/The pleasures of youth are like blossoms in May”, expanding in the final verse into a declaration of a life lived with all its flaws (“I’d have all my battle scars on show/For all the world to see and know/And I’d show them to everyone who asked/And wear them with pride like a map of my past/Beauty can still be seen through the cracks/If we’re looking”).

Quite possibly, the only song to ever include the word ‘funambulist’, the tumbling, waltzlike Ropedancer, was written in honour of tightrope walker Charles Blondin. Sung in his voice, the melody line captures the exhilaration of “Skipping the high wire, gambling and dicing with death/Up where the air is cold and clear/In the calm on the far side of fear”, the subtext being another exultation in being “free as the clouds”.

A more musically experimental note is struck with the not entirely thematically unrelated Fear Not The Mountain (“Fear not the path that is dark and overgrown/Fear not the sunset that brings the day to ending/For it will guide you home… Don’t be afraid as you take the steps to freedom/And you walk that road in your own time”) with its opening multi-tracked vocals imparting a liturgical feel before choppy guitar, tabla-like percussion, and flute bring a 70s prog-folk sensibility.

A second guest backing vocalist arrives with Jake Rowlinson of Windjammer, the Plymouth-based former Midlander harmonising on the gently swaying Call My Name, a song about support in hard times (“When the good idea is out of reach/Try and recall all the good times we had/When you’ve lost the last of your self-belief/Call my name”) and how these too will pass.

With electric guitar firmly plugged in, things get veritably rock n roll for Fall Of The Lion Queen, a driving, urgent Richard Thompson-like number written from the perspective of big cats in a circus as they plan to carry out a “Coup de Cat” on their trainer (“You take the left, I’ll take the right/When she prods you with her stick keep her occupied/I’ll make my move when she can’t hide/On her last day at the circus!”) that returns to the recurring theme of freedom and liberation (“Then we’ll go home, back to the plains/We’ll never see this damned cage again/We’ll escape the ownership of men”).

The three traditional numbers all come back to back, although strictly speaking, it’s just a brace given the first are The Red Rose and White Lily Parts I and II, condensed down from the three-part Child Ballad recounting the tale of sisters Rose and Lily, the king’s daughters. They gain a wicked stepmother who, in a twist on the Cinderella story, has two sons, both of whom fall for their step-sisters, only to be sent away by their mother. With Rose and Lily disguised as men, Nicholas and Roger, they head out into the Greenwood to track down their lovers, where they encounter Robin Hood. Evoking a minstrel-like quality, Part I is delivered with fingerpicked acoustic guitar, woodwind, piano and violin. The jaunty Part II is a more lively number with Seth Lakeman providing distinctive violin behind Roberts’ soaring vocals as Rose/Roger is made pregnant by Robin, she marrying him while Lily weds Little John.

Accompanied by minimal, plaintive piano notes, the third is lyrically more decorous (“We kissed, shook hands and embraced each other/Till that long night was at an end”) but a beautifully and sensitively sung version of the nocturnal lover’s tryst Night Visiting.

And so it ends with two more originals, the first being Bound to Stone, another story song, this time about Sarah, the widow of William Winchester, inventor of the Winchester repeating rifle, who, following first her infant daughter’s death and then her husband’s, embarked on the decades-long construction of the Winchester mansion in San Jose. Legend has it that, believing she was cursed by the spirits of those killed by the rifle (“Others visit her each night, torn by bullets, trapped in place/Relics of another time, reflecting her disgrace”), the only way to protect herself was to continually extend her California residence (“Compelled to give a home to those no longer living”). A mid-tempo piano ballad, the track is sung in the voice of one of the workers who recounts, “For 30 years I’ve worked for her, I crafted every room/Every time I reach the end she gives me more to do/A labyrinth of hidden rooms and doors that lead to nowhere/ Stairways up and stairways down and only Sarah goes there”.

Another history-based number concludes, the stripped-back, echoey parlour piano notes accompanying the vocally soaring Year Without A Summer, the title referencing the 1815 eruption of Mount Tambora in Indonesia and the subsequent brief climate change (“The fields stand empty, frozen hard/The horses starve in the stable yard/And the bright sun was extinguished”). However, the song itself alludes to the storytelling sessions of a group of friends in Geneva, among them Mary Godwin, later Shelley, who was inspired to create the story of Frankenstein (“What makes a man? Is it more than flesh and blood and bone/What makes a man? What desire drives him home?/The certain knowledge we all belong, to choose the path between right and wrong”).

With Almost a Sunset, this highly accomplished British folk duo draw on traditional roots, refracted through a contemporary lens; this is not so much a sunset as the dawn of a glorious new chapter in their increasingly illustrious career.

‘Almost A Sunset’ will be released on March 17th in conjunction with the start of an extensive 26-date UK tour. www.kathrynrobertsandseanlakeman.com/tour