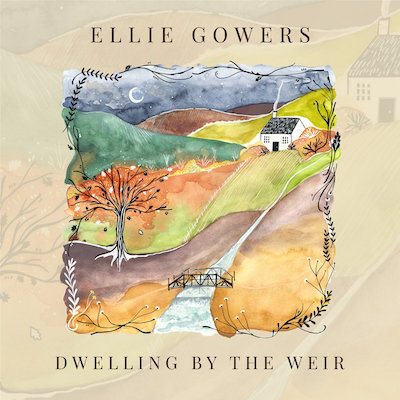

Ellie Gowers

Dwelling By The Weir

Gillywisky Records (GW0003)

30 September 2022

Featuring the ubiquitous Lukas Drinkwater on bass, Ellie Gowers returns to her Warwickshire roots for her superb debut album ‘Dwelling By The Weir‘ which draws upon a range of local stories and characters.

Opening with the pastoral fingerpicked, clarinet-tinged instrumental Introduction, it flows dreamily into the title track, which, with an ambience that evokes a sense of early morning, sets the storytelling stage:

Found myself amongst the tallest grass

Houses line the empty streets

And catch the first light of dawn rising fast

I took the path that looked deceiving

Knowing everything leads to the past

…

I watched the fire and felt the flames,

Was witness to this town as it was drawn

And by the time this land had claimed me

Memories had passed from bark to fawn

…

Writers, weavers, queens and dreamers

Found their way here much like you and I

Settled down and built a home

Connected their lives with each passer-by

And these are tales that will be told

From the lowly mouse to the buzzard high

Steady as the artist writes

Telling tales of what they hear

Won’t you tell me how the story goes

At the dwelling by the weir

The first story is the jauntily strummed Woman of the Waterways with Ewan Cameron on whistle, drawing on the many women who worked on the canals aboard coal boats, shifting coal from Warwick to feed industry in Birmingham and London while also having to look after their family. In particular, it was inspired by Joe and Rose Skinner, a couple who were amongst the last working coal boaters to use horsepower, their donkey pulling their boat up and down the towpath. The lyrics speak of the hardship (“The days are gruelling, and the nights are cold/My hands aren’t as smooth as they should be I am told”) but also of the joy that “comes with the freedom to roam/Along the canals in this boat we call home”. And while “It’s dirty work to shift the coal” and “The water is no place to raise a child/For school is scarce and our only thoughts are about that next mile”, the narrator declares “this life has been long/But oh has this life has been sweet/Weathered dreams bound to tethered seams/But we’d do it all again”.

When the Skinners were older, they retired to a house but would still sleep on their boats, giving rise to the closing lines “as the nights draw in, we sleep one more time under the stars where our lives align”.

Convicted in 1849 for poisoning her abusive husband with arsenic, Mary Ball was the last person to be publicly hanged in Coventry. It’s her story that Gowers tells in the suitably sparse, fingerpicked pastoral A Letter to The Dead Husband of Mary Ball as, adopting her persona, she recounts her tormented life (“You wake under my skin/Clamp my body wearing thin/Arise to violent mornings shared before/I’ve given you six babes/Only one wanted to stay/And still you prise the last love out my hands”), the poisoning (“Have you any regret/As you’re writhing in your bed/The bed I’d wished my end a thousand times… And your body’s lying cold/Warmer to the touch than e’er before”) and then “Taken to be questioned for my sins” and sentenced to death, yet still with a grim sense of humour (“I’m told I’m too be hanged/For an accidental slip of hand/That hand that promised ‘till’ death do us part‘”). A martyr for all abused wives (“I die not for you, but for the women this has happened to”), she’s unrepentant to the end as she defiantly declares “I wear the noose and I’ll see you in hell”.

She returns to a musically lighter mood for the swaying 60s folk rock melody of Brightest Moon, a number that conjures the Coventry blitz during WWII (“Through this quiet town where families dwell/Disruption did approach/A young boy watched from the highest tree/As the neighbouring town perished/In the flames that seared through the tallest spire/Crumbling homes and lives with it”) but more specifically speaks of the kindness amid the chaos “the people they came rushing in/Seeking safety in their packs/They were welcomed in, to every house, every inn/Arms open wide, with the townsfolk saying/Come in, come in/For we’ve a bed that’s soft and a fire to warm you”) as, gathered in refuge, “stories swapped and tales were told/About the lives they’ve lived until now”. It’s a celebration of how people pulled together to help those who had lost everything in the bombing, encapsulated in the account of a confectioner who’s shop was destroyed – “For a silent minute he lay alone/Soon the crowds gathered in and offered their hands/To clear the rubble away”- but who found himself on a “road full of kindness and a path merciful …For he ended up knocking on an old friend’s door/And was welcomed with the kindness he’d given before”. It’s a sentiment we could do more of in these divisive days.

Seth Bye on fiddle, the lolloping Poor Old Horse, is a rework of a traditional song in which, inspired by looking after a 39-year-old horse, she adopts the voice of a self-pitying old nag looking back on his life, happy as a farm horse until he couldn’t pull the cart and was taken in at a riding school (“They tied me to a brick wall, and there I stood all day”), before finally getting to spend his last years being cared for in pastures of plenty where “They don’t make me pull a cart, nor tie me to a wall/But stable me and give me grass until I’m nice and full…I’m happy spending my last days in my owner’s company”. Of course, you don’t have to be a horse to relate to the theme of growing old.

A second guitar instrumental provides a bridge into the final stretch with Waking Up To Stone which, featuring cymbals, muted drums, guitar Drinkwater’s string bass, is another evocative of the traditional-based 60s folk revival with traces of early Joni Mitchell and the Thompson colours of formative Fairport, the song a powerful indictment of environmental destruction, that contrasts happy childhood memories “Waking up in the morning sun/With the bird song on play/We’d tear down the dusted ground/For a chance to seize the day/Trees by our side, and leaves overhead”) with the contemporary reality of development and urban sprawl where “The trees are no more, and the birds they are gone/No chance of shade from the burning hot sun/Ocean of concrete lays on this barren land/And the children I bare will never muddy their hands”.

Again on a theme of a lost past, the penultimate two numbers both concern the passing of an industry. Back in the storytelling mode of Women Of The Waterways, her voice pure as a morning breeze, sung in the titular voice, Ribbon Weaver harks back to the Coventry silk trade that began in the 17th century, originally woven on hand-looms in people’s houses with skills passed down from mother to daughter (“She taught me all her secrets/She taught me what I’m for/Now she breathes through my fingers/And guides me as I work through the day”) with women often dedicating their lives to their craft (“I promised not to marry/For I’m bound to the trade/Woven tightly to this chair/Where she weaved her days away/My feet will still be peddling/Even when I’m old and grey”). However, the coming of the industrial revolution (“now there’s riots, protests, unrest in the streets/About industrial machines/Powered not by feet, but steam”) saw it give way to mass production in factories. But, echoing in some ways Dan Whitehouse’s Voices From The Cones album about how the Stourbridge glass industry has been kept alive by teaching the skills to a new generation of artisans, it ends with her singing about her children and how “I’ll teach them how to weave/Like their grandmother before them/And their children after me/Will keep this loom moving/Until the day it sees its end/And the world loses its rhythm”.

From silk, she moves to coal and the collapse of another industry (“here was a time, when work was plenty/A man could have a job for life/He could think about his future/With his children, and a wife”) with her suitably mournful, minor key take on Coventry melodeon player Pete Grassby ‘s Last Warwickshire Miner, about the last miner to have come out of Daw Mill Colliery in the village of Arley, near Nuneaton. It was the largest colliery in the UK, but in 2013 fire broke out in one of the shafts. It was closed with the loss of 560 jobs and devastatingly impacted the local economy. The former miner asks, “how am I going to feed my family?/How am I going to live?/I gave it thirty years of service/I gave it all a man could give”.

She ends as she began on a theme of home with the folksy gently fingerpicked, piano tinkled, strings and jazzy clarinet-warmed This Ground, its sentiment succinctly summed up in the lines “Now and then I think of where I could be/Somewhere bright, somewhere loud, somewhere chaotic/But for now I’m content with the quiet sound of this town/This is where I choose to wander/This is where my heart belongs… My roots are buried deep into this ground/And I’ll keep them bound” as it swells to a jubilant crescendo and soft close. An affectionate paean to her home country but one with themes and stories that will strike resonances wherever your roots may have formed, it’s a striking debut that launches Gowers into the folk scene as a fully-fledged contender for end-of-year awards and accolades. It would be nice to think that, just as the Arts Council funded multi-media performances of Louise Jordan’s WWI concept album No Petticoats Here, Heritage and Culture Warwickshire might invest likewise.

Order Dwelling By The Weir via Bandcamp: https://elliegowersmusic.bandcamp.com/

Ellie is on tour throughout November 2022, details and ticket links here: https://elliegowersmusic.com/live