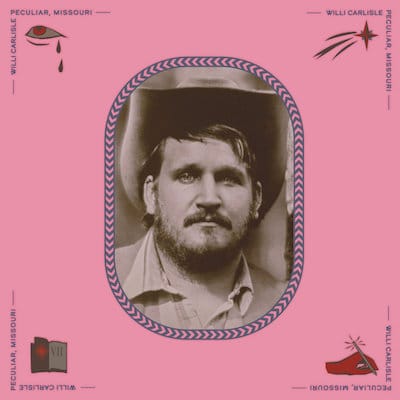

Willi Carlisle

Peculiar, Missouri

Free Dirt Records

2022

I recently caught Willi Carlisle supporting Mama’s Broke, and it was the most fun I’ve had a gig in ages. At one point, in talking about the songs, he had me in absolute hysterics. But not only is he a hugely entertaining and very funny raconteur, holding the room in much the same way as a solo Jason Ringenberg, but he’s also a brilliant songwriter and performer. You need to look no further than Peculiar, Missouri, his second album, for proof. An outstanding collection of songs about connecting with one another channelled through his punk background and his current folk stylings influenced by the music of the Ozarks where he now lives as well as his raising in Northwest Arkansas.

He kicks off in breezy banjo-led bluegrass stomping style with Your Heart’s A Big Tent, a jubilant revivalist midlife crisis number about being born again in anticipation of the end of days (“And I am coming to myself a man finding religion/Am I baptized, drowned, or washed in the blood?/If life’s an open field, I’d like to plant a garden/And get ready for the fire and the flood”) opening yourself up to embrace the world in all its crazy confusions (“You gotta let everybody in/Doesn’t matter who they are/If they do right or where they’ve been”) with the simple conclusion that “The soul is an idiot and it doesn’t care why/Whatever you do with it, the gift’s a pretty simple one/Just sing until you love yourself, then love until you die”, rounding off in characteristic style with the punchline “If I can’t live clean then I’d better love dirty”.

A fiddle-led front porch waltzer featuring pedal steel and dobro, Life on the Fence has the narrator recounting a homosexual affair in Memphis and wrestling with the secret of his bisexuality (“What happened in Memphis made too much sense/There’s a part of my life she don’t know exists/Why is livin’ a lie more easy than life on the fence?”).

That’s followed by a particular storytelling standout, the Prine-like fingerpicked Tulsa’s Last Magician, which recounts the heartbreaking tale of a kid trying to find a trick or skill that would get him some love and attention, of a dysfunctional family (“when his mother drank, he learned to disappear”), before giving up his sleight of hand in the face of always being asked to explain the mystery and turning to a corporate career in computers (“like his second foster dad”), making the numbers sing before realising the years have passed and “now his great escaping act is just untying both his shoes/And most days he’s in the easy chair, yellin’ at the news”, again encapsulating things with a pithy observation about how no one gets who you are – “no one understands/That somebody’s true religion’s always someone else’s joke”.

Cranking up the pedal steel and delivered in a Johnny Cash talking style, Vanlife is a honky tonk romp about those forced to live out of their cars (“Now I’m peein’ in bottles and eatin’ from cans/But ya can’t call me homeless, cause I live in my van …”), the social commentary delivered with a wry, satirical edge (“Call of the wild, call of the road/The endless search for a free commode”), noting all the hassles (“a guy with a house and a big old lawn/Thinks his block’s too good for me to park on/And bangs on my door with a letter that tells/About a thousand ways he can make my life hell”), and ultimately contrasting how “It’s a sexy kinda lifestyle for certain folks” and “here’s some guy like Elon Musk/Talking about how we’re all gonna get cyber trucks” with those who have no other options (“I think, God, life must be easy when you’re one of these dang rich…Gentlemen …it’s a fine line between having to and choosin’ it”).

Things take a Texicana turn for Este Mundo, a traditional cowboy border ballad about water rights featuring bowed bass and banjo sexto, followed by the Woody Guthrie-styled I Won’t Be Afraid Anymore I Won’t Be Afraid, which expands on the theme of not hiding who you are as he sings “I will love whoever I well please/I will kiss my friends upon the cheek/Kiss my friends upon the cheek/Repeat till I believe/I don’t have to be ashamed of what I love”, living your life to the full and at the end “I’ll stand in line and I’ll be counted/I’ll be sorted among the ones that doubted/As for the saved, I wish you well/I’m alright with going to hell”.

Buffalo Bill sets E. E. Cummings’s poem (you know the “how do you like your blue-eyed boy Mister Death” one) to a scratchy dustbowl folk-blues arranged for fretless banjo and rhythm bones, leading into the similarly brief hoedown The Down And Back, Carlisle on fiddle and banjo, sung with the same rapid patter of his days calling square dances with the lyrics again touching on economic disparity (“Workin’ for a livin’ is a pretty raw deal/And Jesus on the mainline is hell on wheels”) and the blind capitalist pursuit of gain (“Won’t ya cut all the timber and mine all the coal/Till half of West Virginia is a fishin’ hole?”), topped with the reminder, “Ya can’t get to heaven in a big black Benz”.

The title track finally puts in a near seven-minute experience, an Arlo Guthrie-esque talking blues backed by fingerpicked acoustic with Joel Savoy on calliope and some words from Carl Sandburg’s poem At A Window as he tells of a panic attack in aisle five of the town’s Walmart and contemplates the nature of humanity and how “we may not have done enough for the world”. It’s appropriately followed by The Grand Design, Carlisle on bluegrass banjo with Savoy on autoharp, accordion, fiddle and guitar, a backwoods spiritual meditation on loss, regret (“All I asked of you is your better years/All I know how to do is waste ‘em/We’ll philosophize on the grand design/And mourn all of creation…I know they said we’d meet in eternity/Still I wait for you below somehow”) and the need for redemption (“ there is evil enough in a half-full cup/To tempt me towards that deep, dark fine…but I heard that there is more/I’m uneasy knockin’ on the door”).

It ends with two traditional songs, the first digging out the harmonica, mandolin, accordion and pedal steel for Utah Phillips’ Goodnight Loving Trail, which, named for the old cowboy cattle trail, muses on growing old and the passing of an era, and finally, learnt from Almeda Riddle of Heber Springs, Arkansas (collected by Alan Lomax), echoingly sung and sparsely featuring fiddle and organ, Rainbow Mid Life’s Willows is an Ozark variation on the familiar folk lament of a love thwarted by disapproving relatives, the narrator’s lover locked in her room and his way barred by her father and brothers (“They said before you enter there/In your life’s blood you will wallow”).

In his notes, Carlisle writes, “This record is in praise of those dead folkies whose honest seeking brought us this unsettling, awkward, fumbling epoch. I’m asking you, them, us: what is it that we can’t find? Who is there but us? Who else will make the world fair and just? …I foam and dance and sing, and look upwards for the shooting star”. We should all follow his example.

Peculiar, Missouri is released on 15th July via Free Dirt Records

Website: https://www.willicarlisle.com/