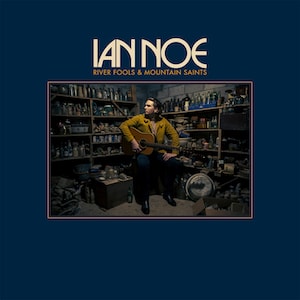

Ian Noe – River Fools & Mountain Saints

Thirty Tigers – 25 March 2022

Ian Noe‘s River Fools & Mountain Saints is a mix of observational storytelling and self-reflection. The grainy-voiced Kentucky singer-songwriter’s second album comes with a more expansive sound, kicking off with the swaggery pedal steel coated Pine Grove (Madhouse), the opening line speaking of the feeling of isolation, of being “stranded” during the pandemic, before reflecting on surviving the changes (“Back when I worked/For the county clerk…when I wore those finer clothes, now them days are gone and we ain’t got long — But I’m still a mountain rose”).

Based on friends who spent Memorial Day weekend fishing and partying, taking a more strummed country path, River Fool, another number essentially about contentment, is the tale of a man from Southfork Kentucky who “spends his days in a muddy haze tangled in the cattail poles”, chilling out on “good ol’ mountain wine”, occasionally hammering out some Creedence on his guitar and “about as free as a man can be”. Then, channelling John Prine and drawing on living alone in his grandparents’ old house, Lonesome As It Gets turns to loss (“She used to stand by the kitchen door while the sun was coming up/She’d always tell me if it looked like rain or if the cat crawled on my truck/Now every morning is a quiet mess with these things I can’t forget”), but still manages a twist of wry as it ends with “I got drunk on Christmas night and had an epiphany:/Let’s end the day in a holy way and set fire to the Christmas tree/While all the bulbs were burning down — the angel was taking fits”. It also includes the inspired image of “I’ve been stranded in the rain so long, I don’t know what’s wet”.

There are more Prine echoes to be heard on Strip Job Blues 1984, a jaunty mandolin-driven number that, back in Southfork, talks of the tough life of the region’s miners (“they say what you gain don’t compare to what you lose”) blasting away at the seams in the mountains while, bolstered by organ, Tom Barrett hews more to Bob Dylan for the first of three numbers about veterans, here “a killing man from the 21st platoon” who can’t escape the only life he’s known (“I never see no peace/On the day I turned 41, I was crawling up a ditch in Greece about to end a man when they stopped me at his heels/Never knew how they handled him and don’t guess I ever will”).

The first half closes out with another veteran (“I’m still the same old baby stuck in Vietnam”) and the acoustic picking and church organ backing of Ballad Of A Retired Man (“Said so long to the highway and that old blacktop crew/Made his way to the mountains where she was waiting up, been 50 years and counting banking more than luck”), a reflective musing on the clock ticking and raging against the dying of the light (“And later on that winter when it took its hold/He saw the man in the mirror beaten up and old”) that samples Muhammad Ali and old TV shows.

The bluesy folk jogging rhythm Mountain Saints opens the second half with piano and hints of The Band as he relates the story of a woman (“hard as hell like a coffin nail”) who lives in the foothills of the mountains and scrapes a living dealing weed. The tempo and mood fall back again for One More Night, a French horn adding resonance to the poignant indigenous people-themed account of a journey to be reunited with kin and to “take the time to recall who we were” that ends in vain (“There were no people left/When the ship rolled in”).

The second of the soldier-based numbers arrive on strummed guitar and rumbling swampy drums with the CCR-echoing POW Blues, which is just what the title says (“They bring our food in the morning/They throw it at our feet/You know it’s foul and it’s foreign/But a man’s gotta eat/They take the time out to tease us/Around and round, they crow/I keep pleading to Jesus/When will they let us go?”). Meanwhile, riding a rolling riff, another bluesy groove, this time more in Dylan style, Burning Down The Prairie returns to the plight of the indigenous people losing their lands (“We’ve been healing from a winter/That brought us more than sleet and snow/You know someone out there somewhere’s/Been cutting down the buffalo”).

Appalachia Haze has it heading to a close in a more subdued fingerpicked mood with the first of two numbers that relate to the floods of 2020 (“Been raining for a week/There’s coffee cans/And an old box fan/Floating in the creek”), following images of change and loss as the years mount up (“There’s plastic pets/And a blue swing set/Rusted in the yard/Said, “Oh, that child/She was always wild/Set in her own ways”), turning a cynical eye on the political response to natural disasters (“The saviors come/To lead us from/This Appalachia haze/Now they’re cutting pines/And power lines/And I watch the gutter drain/Down every ridge”).

Finally, taking a slow walking strum, Road May Flood/It’s A Heartache is weighed down with resignation and loss (“There ain’t a soul in this old coal town/It’s quiet on the courthouse grounds/Just empty cars with windows down”), literally (“last time it rained, I didn’t sleep for weeks/Worrying on those rising creeks/Gravel bars and busted beach/And mountains made of slate”) and metaphorically (“say it’s been a haunted life/I use to have a Christian wife/And I lost her like a pocket knife/Sliding down the bank”) lost in the flood as, with guitar twang and strings, it morphs into the Bonnie Tyler classic about life as a fool’s game that leaves you “Standing in this cold rain/Dancing like a clown”.

His inspirations come from autobiography, the Appalachian community and observations of the characters that inhabit it. Still, the emotions he touches on and the stories he tells have a universal resonance for all the world’s river fools and mountain saints.

Order River Fools and Mountain Saints here: https://orcd.co/riverfools