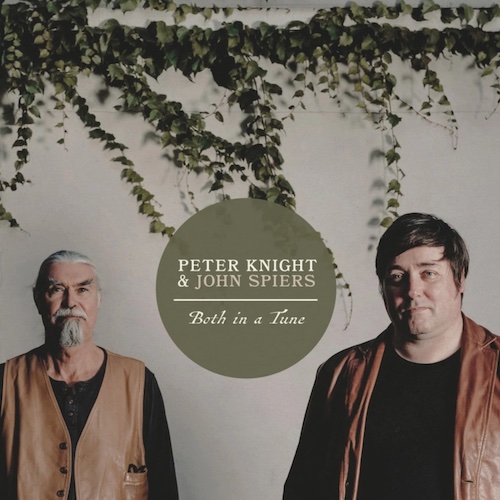

First recording as a duo back on 2018’s Well Met, Peter Knight and John Spiers return with the glorious Both in a Tune. You can read our review of the album here, but back in January, Folk Radio UK got the chance to chat with Peter and John about the new album, Both in a Tune, the excitement of free improvisation, comparing playing to 90 minutes playing as a midfielder and the beauty of being lost in a tune.

First of all, we chatted about how the duo, Peter Knight on fiddle and John Spiers on melodeon, first came to play together, and it turns out the story began at FolkEast Festival back in 2016, as John explained:

“Well, it came about because of an email I sent to the people at FolkEast. At that time, I’d not long left Bellowhead and was doing solo stuff and feeling that the best way to make new musical connections was to just randomly play with people. But I didn’t quite know the procedure to start doing that because you can’t just run out, ring up random folk you haven’t played with before and go, ‘you fancy coming over for some tunes, see if anything comes out of it’!

“I saw that some festivals had put out feelers about collaborative projects and because I’ve got quite a close relationship with FolkEast, I felt confident enough to email them and say, ‘if you’ve got any kind of collaborative things going on, then I’d love to be part of it’, and they said, ‘well, Peter Knight’s playing, do you fancy doing something like an impromptu thing with him?’ And that’s when it started off.

“Peter very kindly came around before the festival and we did a bit of playing together, but not much. I mean, it was a couple of days. We showed each other YouTube videos of music we liked and played tunes that we really liked to each other, and if the other one thought they were worth learning, they learnt them. Then we just went on stage and played with no real arrangements in mind! The gig went down a lot better than I was expecting it to! But, then I’ve probably got quite a bit more self-doubt about my playing than Peter!”

Following the FolkEast gig, John joined Peter’s Gigspanner Big Band before releasing their debut as a duet back in 2018. Both in a Tune develops the duo’s partnership delivering some exciting new tracks as well breath-taking reinterpretations of several traditional tunes. Take the opening track, for example, an exhilarating take on that old favourite ‘Scarborough Fair’. Its inclusion on the album tells much about the organic process of how the duo worked together and their love of traditional music, as John notes:

“I love the way you can’t quite tell that’s what the track is if you didn’t know what it was to start with. It sort of crystallises in the first minute. It was a tune we both knew well, and it was chosen because it felt like it had those possibilities, we might have had a few play throughs just to make sure we were playing the same version of the tune, in the same key, before we actually went in and recorded it, but what you hear with that one is very much the entire process as we play gigs live. I don’t think we did much mucking about with how it was mixed and edited at the end, that’s just us sitting down.”

The titles of Well Met and Both in A Tune reference the plays of Shakespeare, in particular As You Like It. This wasn’t a planned idea, though and came about more by happy accident than any other process:

“What’s interesting about that is,” as Peter notes, “after John and I recorded the album, we were both thinking of titles for the album. It’s never an easy thing.”

“I hate doing it!” concurs John.

“It’s never easy!” adds Peter, “There’s a lovely traditional song, I think it’s called ‘The Husbandman and the Servingman’, and it actually starts ‘well met, well met, my friend’, and I just thought of that, and I thought about how John and I started playing together, and I just thought, ‘well, that’s really nice!’ It was nothing to do with Shakespeare whatsoever at that point. I called John up and said, ‘what about Well Met, and he went ‘Oh, I really like that’ and that was that!”

“When it came to the next one – Both in a Tune,” adds Peter, “it was my wife, Deborah, who knew that there was a Shakespeare connection. She found a particular verse. I remember walking into the kitchen, out of my studio, and Deborah said, What about ‘both in a tune’? And I thought, ‘I absolutely love that. And thank you, Shakespeare, and Deborah!’ It really, really suits what John and I are doing.”

“What’s lovely now about John and I playing together is that when we said, what about ‘Scarborough Fair, we all know that right? What key? Well, let’s have a go at it.’ Microphones were set up, and we just started playing. It comes back to that thing about being comfortable with your chosen endeavour and what that is for us is to play these tunes in a way that’s interesting to us.”

“There’s a reason why I want to play tunes in that way,” continues Peter, “is that it leads to music that you can only find by approaching it in that way, those incredible moments that you can only find by deciding that that’s what you’re going to do. So, this ‘both in a tune’, that’s sort of where you are – you’re both there, you’re both in the tune. It’s the tune that’s the star of the show, not the players. It’s absolutely perfect. Yeah, I love it!”

For John too, the title immediately worked: “I loved it the first time I heard it, and I didn’t realise that was the quote. I thought it was ‘both of a tune’, which wouldn’t have worked, but the idea of being in a tune – inside the tune – the space of the tune. That’s where all of our motivation comes from. It’s exactly what it’s like when we play on stage together. It’s an incredibly different way to the way I’ve played with any other musicians before.”

The title too sparked off a discussion regarding the enjoyment of playing, as John explains:

“They say time flies when you’re having fun. I’ve had 45-minute sets that have felt like they’ve lasted two hours – like a marathon slog! The gigs with Peter – you look up and it’s half time, and you go, ‘where did that go?’ Because you’re so deeply concentrating on making the music, that time just doesn’t do what it normally does! So, you are literally inhabiting a very different space. I mean, for me, I’m not really (in the live gigs), I’m not really aware of the audience, and that sounds pretty bad! But I’m literally only thinking about the music!”

“Yeah, absolutely John,” Peter enthusiastically agrees, “and I have great faith in audience’s ability to know when people are really trying to express something through music.”

The chat shifted, naturally, to a philosophical consideration of what music actually is – a complicated question, but Peter has several thoughts on this:

But how lovely sometimes when you’re playing, and you’ve arrived at a place, and you’re not quite sure how you’ve arrived there. But it’s the most beautiful music you’ve ever heard, and you’re playing it!

“Musicians would not ask themselves the question, ‘what is music?’ They might ask themselves,’ what music am I capable of earning a living with?’ Or ‘what music do I like’? We all have to start somewhere, and we all get inspired by certain types of music. I think once you’re touched by this free improvisation, then you have to ask yourself the question, ‘what is music?’ If you are a musician, you’re expressing something through a sound source and a sound source of your choice.

“The next question is ‘what do you want to express?’ You really do have to go back to basics – ‘what is music, and how can you make the best music?’ I’m not talking about entertainment. When John and I go out and play, the sort of comments that we get from people – that they get transported to somewhere they haven’t been before, and I get that quite a lot on gigs; ‘thank you, you’ve taken me somewhere that that I haven’t been’. Well, we have to take ourselves there too, in order for that to happen! And it’s a very, very exciting place to be!”

“Someone once said,” continues Peter, “I think it was in a film or something: ‘don’t be frightened of the unknown because it’s a fabulous place when you get to know it’. It’s that lovely feeling of making music, or not quite sure where you are on the instrument or where you are with anything. I don’t mean disappear in some airy-fairy way, you can’t disappear completely, because if something goes wrong, you have to be there, to put it right! But how lovely sometimes when you’re playing, and you’ve arrived at a place, and you’re not quite sure how you’ve arrived there. But it’s the most beautiful music you’ve ever heard, and you’re playing it!

“And then what you have to do is to say to yourself ‘keep it there!’ It’s the music that’s important. Then you’ve got all the thing of egos and ‘this sounds really nice’ and then maybe you start feeling a bit guilty about it! But don’t! Hang on to it! It’s not to do with you, it’s to do with, as a musician, playing the best music that you can, that you can make. When it arrives through this form of making music keep it there, keep it there, just enjoy it. It’s a privilege to be able to play music in that way when it works. It’s getting me excited now – I just want to go and do the gigs!”

This process, as John agrees, is exciting and one that ties into his own experience of practicing:

“It feels like a very natural way to make music, as Peter touched on. I don’t come from any other real kind of musical background other than the self-taught, sort of accumulator of other people’s ideas and style. Apart from when you get to a certain level on your instrument, you can then start mucking about.

“I’ve always treated most of my practice regime as just exploring, not even playing things, but just looking for patterns and stuff – when I know no one’s listening, just me, giving myself feedback. A lot of the things that are more composed, that I’ve done in the past, have come entirely out of that.”

“I’ve always really enjoyed that,” continues John, “The same thing happens, you don’t realise what the time is and you should have been making dinner or something, you realise that you’ve been playing for hours on your own!”

Whilst this has been at the root of John’s habit of practicing, it was a new experience to add into his performance structure, and it’s clear that learning from Peter has been thoroughly stimulating:

“I think, possibly the second gig we ever did together,” says John, “the scales fell from my eyes, and went ‘oh, you can do that on stage, what I’ve always done at home!’That freedom, and the idea that I need to really appreciate that side of my playing and give it some time and give it some thought. Peter’s been the perfect person to do that with. I just love that whole freedom. I love the traditional tunes that we choose, and I love the fact that I can constantly play with them. I just love everything about it!”

“I feel the same!” agrees Peter, “How John accompanies tunes is quite extraordinary. What’s developing between us is where dissonance becomes harmonious and that’s just beautiful.”

“In western music we’ve got semi-tones, Bulgarian music has quartertones, and worldwide there are all these incredible harmonious intervals, and when we’re playing them we’ve hit areas where it’s just extraordinary. What’s lovely about John is, I do think John gets bored with music sometimes, the same as me, and there’s nothing worse as a musician where you’re playing but you’re not really engaging because there’s nothing to engage with. But John changes his left-hand accompaniment all the time through the same tune, and that’s really nice! That is absolutely lovely, it’s a joy to play music with John!”

“I don’t think I’ve ever fallen out of love with my instrument,” adds John, “I really enjoy it for just banging out a tune, I just love playing! But I think it’s more that there have always been days where I feel like I want to throw my instrument in a bin when it’s not doing what I want it to! Really that’s not the instruments fault. Most of the time! You just have days when you feel like you’re playing like a sack of horseshit. And days when you feel like you could conquer the world with it. I don’t think I’ve learned how to make those days happen more often, I’ve just learned to appreciate them more!”

At the root of the duo’s playing is the process of free improvisation, a challenge to those more accustomed to rigid arrangements but incredibly freeing and invigorating for those willing to explore it. It’s a process Peter has long experimented with:

“I suppose it really was in the 80s,” notes Peter, “I mean, I’d always done it, but hadn’t taken it seriously. Certainly, on gigs I thought that improvising was taking the tune and then just embellishing it slightly differently each time; putting a few little twiddles in and whatever. But as far as just picking up the instrument and maybe starting somewhere that you’ve never started before and to develop that with a trust from the very first note that you play and giving it a feeling and then developing that feeling I’d never done that.”

“I think it was in the 80s that I started playing with the sax player Trevor Watts. Trevor is an extraordinary musician, and I think it was then that freely improvising became the basis of my relationship with music, really.”

“It’s different every time I pick it up,” Peter continues, “It sounds different every time I pick it up. I go in my studio every day, and I work on something, whether it’s rhythm, I’ll set up some rhythm tracks and play along and just practice. The thing about improvising and especially an open improvisation, even if you’re connecting that with a traditional tune, and while you’re openly improvising, you’re actually thinking of the beauty of that tune. John and I do that on a few songs: ‘Rose Bud in June’, that we’ve played in Gispanner a lot, we don’t start with a tune, we start somewhere else, but we’re thinking of the beauty of that tune while we’re doing it.”

“It makes you want to practice. There are times on gigs when you’re discovering something between you as musicians. Sometimes it might be technically quite difficult, when you’re doing some repetitive thing with your fingers and on your bow, and you’re playing, and then you want to stay there, but your fingers start getting a bit tired and the muscles don’t work properly. So, it makes you want to go home and go, ‘I don’t want that to happen again. I’ve got to practice that!’”

Whilst the process of free improvisation has long thrilled Peter, it was still a relatively new experience for John, although he had explored it in the past:

“I wasn’t a complete stranger to it,” notes John, “but in context of doing it for performance, I was, to some degree. I’ve always mucked about with the tunes in the context of the arrangements that I’ve been trying to play. It’s something which I’ve really enjoyed getting my teeth into and I feel like it’s kept me growing as a musician.”

“The thing you have to realise is that Peter mentioned quarter tones earlier and things like that, I don’t have any of that! I just have out of tune notes! Playing a diatonic squeezebox, I’m also limited into how far I can modulate out of a key, which keeps my part of it slightly grounded. There are limits to which the instrument will allow me to take the music in some ways but not in others. So, I have to look for things that the instrument can do.

“So, I just feel the whole process has made me understand my instrument more and grow as a musician. That approach of being free to do what I want to do has been a growing experience. I think that’s the only place I would have wanted to go at that point in my career as a musician.”

“Having spent a lot of time playing quite functional parts in a larger ensemble”, adds John, “there’s a lot of great music that comes out of that approach, but it’s for live – it’s not a creative process. Really. It’s like the difference between playing football and being a rower in the Oxford or Cambridge boat race. I did row at college, you just have to row, and you have to roll at the same speed as all your other mates, otherwise, you catch a crab, and it knocks your head off! With football, if you’re a creative midfielder, you can be changing the way the whole game goes with your individual action. Those are the two extremes in music. I’ve not really fully embraced the more creative live approach before, because of the situations I found myself in. This was a new outlet, which means that I just have a whole new set of skills to work on that didn’t. I didn’t have an incentive to work on before, and you can only really hone them down by doing them. It’s been easy to find the motivation, and a lot of it is about confidence, confidence in yourself to deal with the situation. I have to be in control of what my instrument does in order to be confident that I can let the music that I want to get out, out.

“I think it’s all about just believing in that way of making music, and so playing with John was absolutely lovely,” adds Peter, “He is an enormously fantastic player, and John will tell you himself that when we got together, he had always messed around at home in a practice session, because before something becomes a piece of music, that’s written down and played, it’s sort of an improvisation.”

“Having done so much free improvisation over the years with different musicians”, continues Peter, “and on my own, which is not as much fun I have to say it some; it’s probably less problematical in some ways, but the interesting area for me is, is freely improvising with another musician, when you feel that there’s a musical dialogue going on between the two musicians, which is just a stream of consciousness, musical consciousness, and it leads for some very, very exciting playing and very, to me beautiful music.”

“I said,” adds John, “when I did that first gig, I didn’t have much confidence before it because I have very little experience of playing in the way Peter described earlier – open and free with another person in front of the public – but because of the process of all the gigs and the recordings we’ve done over the past few years, I had total confidence going into that- that we were capable of ending up with something that sound sounded great.”

“It seems weird to talk about your own music!” John continued, “I don’t normally talk about my own music if it’s something I’ve composed. Normally, with something that you’ve sat down and worked out an arrangement, I wouldn’t normally go, ‘I really like that bit of my own tune!’ But the thing is, for us, when listening back now, I can see the process happening and there are little moments in a tune that stand out to me, because I know that that process was entirely in the moment. So, there are a couple of points in a tune – it just gets really meltingly beautiful. Part of the joy of that is that it’s just come out of us; it wasn’t planned apart from in the moment.”

Before we finished, we chatted a little about some of the tracks on the album. Traditional English tunes make up the body of the album, but there are a few nods to Peter’s adopted homeland of France, which link to John’s interest in French folk tunes too:

“It’s lovely living in France,” says Peter, “It’s quite remote where we live.”

“‘La Dance De Madame Meymerie’ – I thought I’d like to write a tune for the album and I was practising a rhythm thing or something, and I just happened to hit that. Madame Meymerie is our neighbour, she’s 86, she’s absolutely lovely and was born in the hamlet. Her and her husband were sheep farmers originally, and she’s just lovely. The other one, ‘Le Berger De Laleuf’ – one of our neighbours is a sheep farmer and one of the tunes that we play is ‘Shepherds Hay’, we call it ‘Signposts’ on the album, but it’s actually ‘Shepherd’s Hay’, so I wrote a tune to accompany that, so that’s where the French names come from.”

The third one,” adds John, “‘Bourrée De Concours’, is one that I’ve played in local sessions in Oxford, for as long as I’ve played all the other English tunes, so it’s kind of part of the repertoire. One of my hobbies is playing French folk music when I’m not playing English folk music. There’s a brilliant French session based in Oxford, and I’ve often gone there just to let off steam and play good music with people in an informal atmosphere. Along the way, I pick up all these other tunes that aren’t really what I’m known for playing. France isn’t all that far away; it’s closer to me than some bits of Northern England, so I don’t see any difference in the tunes. Really, I just love them. So that’s where that came from.”

One of the final tracks on the album, ‘Union’, is a particular highlight. Written by John, it’s a track with a history back to John’s early days:

“Well, the name of it comes from the reason it was written,” explains John, “it was written a long, long time ago, before I really had any gigs or anything. My musical career consisted of being a Morris musician, and playing in pub sessions, back in the late 90s. Two lovely people from the Oxford folk scene got married, and I couldn’t afford a nice present for them, so I wrote a tune instead. The title has no meaning other than the union of those two people’s lives into one family life. I thought a lot about them when I actually wrote the piece of music. They both played and danced, and I knew that one of them had a love of Scottish music. I tried to channel my experiences of Scottish music into that so you get little hints of things that you don’t really get in English music.”

“It’s supposed to be a slow piece. It has that little phrase at the very beginning where it’s got what I call backwards dotting – the same sort of measure you get in a strathspey. I played it to Peter and he liked it, so we recorded it!”

One thing that strikes listeners about Both in a Tune is its sound. It has an incredibly luscious large sound, and it was something Peter and John actively sought:

“We worked with a couple of incredible engineers, especially Stuart Jones at Woodworm Studios who took all the tracks and mixed them for us”, notes John, “Listening back to it, that’s really paid off.”

“I’ve often overlooked the importance of recording something,” John continues, “I can listen to source recordings from the 1910s and go ‘oh, there’s an amazing bit of music there’ and really enjoy it with all the cracks and pops and difficulties of the recording technology at the time. And I think it was Peter that really drove, trying to get as good a sound as possible as we could with just two instruments. Then a little bit of Pete Flood on the drums as well; we’ve just got this very big sound that we’ve created for some of the tracks.

“The penny dropped for me listening back to the ‘Abbot’s Bromley Horn Dance’ that one made me go ‘ah, yeah! The whole thing, the playing and the sound and the lovely drums that Pete put down for us and the way it was mixed’. How you sound to yourself is very important. When you’re playing a gig, if you can’t hear what your instrument sounds like properly, it’s difficult to play as well as you can. I think we’ve given ourselves some lovely sound to work with on this album.”

“What’s lovely about John and I playing together,” adds Peter, “is that we both love traditional music, and since the first album it was necessary, certainly for me, and I think John probably agreed is that we wanted to push the boundaries just a little bit more, that was very important. Because I think if you stay the same, the perception is that you’re going backwards. I think you just have to keep upping the ante a bit with your endeavour, trying to make music in that way that John and I are making music, which is to try and be as open as possible when we’re playing the tunes and to talk about other’s approaches.

“So, I mean, bottom line, I absolutely love playing with John. There’s no doubt that since our first album, and since we’ve done a couple of tours, the playing between us has got much more interesting as far as I’m concerned. There’s a trust now between John and I, there’s not one of us that loves music any more than the other. But now and then on the gigs, we hit certain sounds, and certain areas and textures that are absolutely incredible. I get very excited!”

The duo take to the road in February, playing 26 gigs across the country, and it’s clear the duo are thoroughly looking forward it. Fans of both musicians will already know what a thrilling evening of music will be on offer, and it promises to be equally as exciting for the performers as will be for attendees.

“The object for me”, notes Peter, “is to come away from a gig and really feel that you’ve expressed your love of music in the best way that you can. So, it’s a very exciting duo. I’m really looking forward to our tour in February!”

“I think there’s some lovely playing on the album,” adds Peter, “it was not a difficult album to record, really, we were always in one frame of mind when it came to listening to the pieces and deciding if we wanted to put our own stamp of approval on it and say, ‘Yeah, I’m happy to listen to that.’”

“Sometimes when you’re listening to music you’ve recorded, and you’re in the presence of someone else who’s listening to it, you have doubts. It’s a horrible feeling because you say to yourself, ‘why did I let that go out publicly? When I’m actually not that happy with it myself?’ And I never felt like that about anything on this album, so playing with John is an absolute joy!”

Both in a Tune is an absolutely glorious listen, layered with vibrant musical expertise, skilful invention, and the palpable joy of experimentation. Peter’s fiddle and John’s melodeon strike the perfect duet. A thoroughly enjoyable and exhilarating listen and the perfect illustration of how fresh and vital traditional music can still be. Treat yourself – don’t miss it!

Both in Tune is released today – 11 February 2022.

Order the CD via the websites of Peter Knight or John Spiers

Peter and John are on touring their album from 23 February through to March. Click here for details and ticket links.

Photos by Elly Lucas