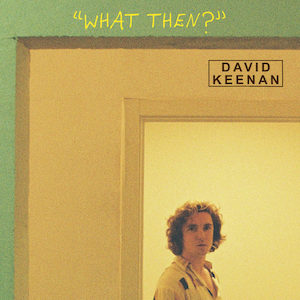

David Keenan – WHAT THEN?

Rubyworks – 2021

Last year, Irish ex-pat David Keenan of Dundalk, County Louth (now based in Dublin) released his astonishing debut album, A Beginner’s Guide To Bravery. The album, reviewed here, was a heady brew of Van Morrison, Tim Buckley, Samuel Beckett, James Joyce, Charles Bukowski and Tom Waits. It was like nothing else before it and was rightly acclaimed as one of the year’s finest. He’s back now to claim a second trophy with an equally electrifying album that, this time, draws on his own experiences as the source of inspiration and, as captured in the title, ‘What Then’, its existential angst. Again, featuring drummer Aaron Steele, Will Honaker on bass, violinist Mel Guerison, steel guitar by James Paul Mitchell and Jonathon Mooney on keys, it’s populated with references to religion, drink and the human condition, looking up at the stars from the gutter of life as God pisses in your eye.

It opens with the circling Waitsian junkyard clattering lope that is What Then Jo Soap? with its lyrical howls of desire (“I’ve sown new seeds I wish to grow, embrace the many gifts that life bestows upon me”) and disorientation (“As the alcohol took hold, the level of noise began to rise”) in its search for meaning, moving into the drums-driven urgent cacophony, violin shrieks and Eastern swirls of Bark with lines like “Wretches on crutches sing Ave Maria” and being “Caught between a headbutt and a hard place to be/Spilled into a park bench, a bank holiday Monday casualty/A pale fabrication, a mascot for emasculation” that circles questions of identity and being your own man (“Beyond reproach I am free free free/From the plastic smiles and the monotone souls”) and not barking like a dog when told, which, featuring spoken oration, builds to a literally howling climax.

By contrast, forged from hard times as a teenager (“From left to right we’d hop and bounce, from wall to wall in that council house”), Beggar To Beggar is a catchy unbridled slice of scurrying pop that put me in mind of Hothouse Flowers with its notion of contrariness (“You say one thing and I’ll do the other”) and again canine imagery (“the dogs bark their disapproval”).

Shifting mood and tone once more, the pulsing, slowly gathering Philomena is a tribute to his late grandmother, contrasting her nurturing (“Philomena tell me a story, sing me to sleep, I’ve been in the Wars”) and the spirit and salvation of home and family with the “sanctimonious scum”, “working class Magi” the “slum Queen” and “crack King”, those “Who would sell you for buttons in a heartbeat/Who would live inside your ear in an instant”. Adopting his Jo Soap persona again, he lays bare his soul in a confession of “consuming hard drugs and vile wine” and how “You can take the lad out of the Council estate” and that “In the clothes of a stranger I wibbled and I wobbled and I wandered directly towards the holy cesspool”, a darkness counterpointed by recollections that “When we were younger it always seemed to be sunny/We’d steal cigarettes and buy clothes from a man in van”.

Along with his powerful poetic turn of phrase, he has a gift for song titles too, such as the booze-fuelled Peter O’Toole’s Drinking Stories with its semi-spoken stream of consciousness recalling romantic clichés of what it takes to be a struggling artist (“I wept on the unmade bed of existential crises/Came to believe that all you need to be a writer is a coat/One arm as long as the other brother”), and describing himself as “a six week premature ejaculation baby”, a raw open wound snapshot of family (“Once upon a time my Mother was a lady/An OCD fact grilling machine, that was then and that was that/Once upon a time my father was a coward/But I love him for who he is in the present”) and mental breakdown (“the boy has snapped we’ve never seen nothing like this before/All the bells have tolled he’s never coming back, cracked, smacked, stoned”).

Riding a galloping Latin drum rhythm with a time signature shift midway, the oxymoronically titled Hopeful Dystopia is another swim down the stream of consciousness, offers some whimsical wordplay, rhyming Valerie and gallery and talking about “the tomb of the unknown gurrier” (an Irish term for an unruly young man), a playful presaging of apocalypse (“Blow out your candle it’s four in the afternoon and the world as you once knew it will be ending soon”), with images of perdition (“Where is the sunken Lusitania you’ll forever row?”) and contempt (“I could never ever think any less of you/When was your last decent deed?”), but ending with the wry “Where is the fake Francis Bacon triptych you said you owned?”.

The Grave Of Johnny Filth welcomes the first of two guest contributions, his Scottish poet namesake providing the brief intro giving way to strummed guitar and piano before the spoken account of the titular character “loosely based on a member of the human race”, which is essentially about disillusionment with fame (“A patchwork of dreams came and went… There was no rumoured pot of gold”), revealing itself as a “landscape littered with bric-a-brac/Deck chairs stripped of their hides/Defects of character scribbled on borrowed pages”. He’s spoken about the need to get away from those who “greet me with kisses on the lips/An occultist code I’ve yet to unlock”, echoed here in the line “This is my first mouthful of clean air in eighteen months”, and to “climb through the hail and through the rain” and find himself “Now my primary purpose is to speak to the land”.

Piano takes waltzing pole position for The Boarding House, a story of seduction and again a number about escaping from ties and obligations, seeking salvation in companionship without commitment or judgement (“Tonight I want to lie with someone who doesn’t care/If my laces are tied or my background is poor/Is this too much to ask, take this lock of my hair/And lead me to a lover up the creosote stained stair”), again returning to images of embracing the real over the celebration of the fake (“Her head of tangled curls remained untouched by chemicals/An ancestral trait that made her mother proud”).

The simple fingerpicked acoustic Me, Myself and Lunacy, apparently born of a night in Paris where he lost his apartment, is underpinned by the need to find calm in the storm of turmoil and reconciling with mental health issues (“a multitude of thousands live inside my head”) as a result of everyone wanting a piece of you (“it’s hard to accept that your mind is sound/When your heart’s become an art exhibition/And it’s hard to inspect, whether your mind mind’s still fried or wrecked/When your life’s become a public execution”). But even here, Keenan’s sly wit surfaces in lines like “ideas practising yoga stretch” and the punning “Undertaker by trade, grave by nature”.

The second guest spot is filled by another poet, Stephen Murphy, contributing spoken word underneath the play out of Sentimental Dole, another tapped percussive Latin inflected rhythm, that again concerns self-determination in the face of those who, “living among us masquerading as a friend”, “put you in a chokehold, keep you down until your dead/This is mass discrimination on every colour every creed/For to them you’re just a number both the cattle and the feed” and rising up “no longer a pleb to be played/Like a pawn in their game”. It also carries one of the album’s most resonant lines: “Loneliness the silent killer/Takes and never gives you back/For it steals and can’t stop stealing, a twisted kleptomaniac”.

It ends with Grogan’s Druid (presumably a nod to the famed Dublin pub), a Celtic twilight strummed slow waltz that features the voice of his grandfather and laughing family members as it draws a portrait of a barfly sage in Dunlop runners (“Christ-like he sits drinking his ale/Herding his sheep over whimsical tales”) who mesmerised the young Keenan and (“I hung on every single word that he said”) and lit the spark within him (“He told me that I might succeed and he gave me a sense of belief”). If he’s still around, we should all buy him a pint in gratitude. An album wrenched from the jaws of desperations and into the arms of hope, to draw a comparison with Joyce, it builds on his phenomenal debut in the same way that Finnegan’s Wake was a quantum leap from the groundbreaking Ulysses, a defining work of visceral genius from a soul aflame with both the poetry of his ancestors and the fire of the future. The tantalising question is, What Next?

Peter O’Toole’s Drinking Stories (Live at The Olympia)

Order WHAT THEN? via Amazon