Come, me little son, and I will tell you what we’ll do:

Undress yourself and get into bed and a tale I’ll tell to you;

It’s all about your daddy, he’s a man you seldom see,

He’s had to roam, far away from home, away from you and me.

But remember lad, he’s still your dad though he’s working far away

In the cold and heat, eighty hours a week, on England’s motorway.

It was thanks to a lullaby by Ewan MacColl that John Frances Flynn learnt how to sing. He calls the instant he first heard Luke Kelly’s version of Come My Little Son an awakening, which led to the then twenty-year-old Flynn performing it at every given opportunity. Although the narrative of “England’s Motorway” sounds specific (referring to workers MacColl encountered on the M1), its message is a universal one, as Lisa O’Neill once explained to the Irish Times: “(It’s) from the perspective of a wife and mother back home, explaining to her son the reasons for his father’s absence, and what he can and can’t rely on his father for. Sadly, this human tale is as old as the hunter gatherer and worldwide as current as current can be.”

Up until that point, Flynn had been making his name as an accomplished multi-instrumentalist, mastering the tin whistle and flute early as part of one of Dublin’s traditional music youth orchestras. Later, a regular session player at The Cobblestone and Walsh’s, he was surrounded by folk singers, though at this stage, he was still to take the practice himself. The next lightbulb moment for Flynn came whilst studying at university, after hearing The Watersons’ take on The Thirty-Foot Trailer (another MacColl composition) during a, particularly memorable lecture. Recognising the Salford songwriter’s genius, as well as the power and potential of traditional song, he soon fell under the spell of artists like Kelly, Shirley & Dolly Collins and Dick Gaughan. “I may have dropped out of that course, but that course formed who I am today,” John recently told Donal Dineen.

For MacColl, traditional music was the testimony of the working classes, and he fiercely encouraged its evolution. It’s no surprise then that the themes of dislocation, strife and courageousness that appear in Ewan’s Radio Ballads resonated so deeply with Flynn, as they’re recognisable throughout his remarkable debut. I Would Not Live Always is as indebted to the everyday folk who live and labour within these songs as it is to the folk revivalists who sang of them. When asked about the meaning behind the album’s title, Flynn explained that it too relates to a sense of unrest:

“Well, The Dear Irish Boy is about wanting to be home. You know a lot of people have gone abroad because they have no choice, they can’t afford to stay put. It could mean any sort of struggle though: wanting to be with the person or place that you love. Whatever home is. If something is unfortunately standing in your way, you would hope that ‘you would not live always’ through that. I mean take the current housing crisis in Ireland…”

However, Flynn’s quick to note it’s open to interpretation. The title could also pertain to the way in which the song outlives the singer or the way an album can feel like its own entity, separate from the artist after its release. This thinking strikes a chord with Flynn:

“I think about that very regularly when I’m singing these songs or playing traditional music. Because the songs will always outlast you, that’s the power of trad. The connection you have with the past and future, you are part of the journey those songs have come on and by singing those songs you’re connecting with someone else’s experience from the past. Then it could go on to inform something in the present. I think that’s quite a powerful thing, the fact that it’s all bigger than you.”

The songs that make up I Would Not Live Always certainly feel time-honoured, and the emotional range Flynn applies to each one is staggering. Take his closing rendition of Come My Little Son, for example, his tender vocal on this enduring swan song is a world away from “absolute belter” My Son Tim. There’s something of Richard Dawson and Jeff Mangum in his voice, not necessarily in the tone, but rather in its honesty, rawness and the way he handles it. It’s something producer Brendan Jenkins would surely attest to: “There’s harmonics that come from John’s voice that I think often singers might sometimes try to suppress. I found that really interesting in how I would approach capturing it… I wanted to record it in such a way that it sounded like John was almost inside your own head when he was singing.”

Whether it’s touring Europe and the States with Skipper’s Alley, spending twenty-five “soul-destroying” days playing music in Darby O’Gills pub aboard a Disney Cruise ship or performing on major works like Ye Vagabonds’ The Hare’s Lament & Lankum’s Between the Earth and Sky, the trad life has taken Flynn to some pretty far-out places. His tour with the latter in 2019 proved to be particularly fortuitous, leading to his River Lea record deal. But for Flynn, it meant everything just to be back in the company of Peat, MacDiarmada and the Lynch brothers again:

“I’ve always been mates with them. We used to very regularly be singing songs together at parties and playing tunes until six o’clock in the morning. Then they took off and they’ve been so busy that there’s not been the same time for that kind of thing. So, it was really nice to go off travelling on tour and to be hanging out with them for like a week and a half. It’s good the journey you can see, which we’ve all come on.”

When asked how it feels reflecting now on his friend’s success and the increased interest in Ireland’s traditional music, Flynn’s answer is a humble one:

“It was a very underground thing, not that we were thinking that it was as such. Traditional Irish folk music hasn’t been mainstream in Ireland for a long time. I’d always played it, but when I started playing songs it was encouraging to find other musicians that weren’t necessarily from a trad background singing songs as well. Many bands started out of that. But I don’t know how far we actually thought that would take us. We weren’t setting up bands to take over the world or anything like that. We didn’t think many people would be interested; we were just doing it for the craic. I suppose when people started really taking notice of Lankum that opened the doors for everyone else to say, ‘actually maybe this is a goer, perhaps we can do something here.’”

It seems this feeling wasn’t exclusive to just Ireland’s folk community either. When we spoke to River Lea’s Tim Chipping, he echoed a similar sentiment: “(Lankum) changed all of our lives, really, in the possibilities their approach to the music has opened up. Sometimes it takes one band to make the path ahead visible for others. It’s definitely not a scene; everyone’s doing their own thing. But there’s a shared spirit and understanding.” Lankum’s impact can’t be understated; it was even members of the band that put Chipping onto both O’Neill and Flynn; however, it was another crop of Irish talent that John had in mind when he conceived the idea of recording a solo debut. When questioned about whether it was always his intention to naturally blend electronic and traditional elements, he tells me it was, but the most crucial aspect was choosing the right artists to work with:

“With the solo project, I wanted there to be no boundaries on what I was doing. Basically, my idea was to collaborate with some people who definitely didn’t have a background in traditional folk music, get them on board and explore some more electronic sounds. It was Ross Chaney who plays drums, Tascam and synths, and Brendan Jenkinson who brought that kind of influence.

“I had a gig at Body & Soul festival and it was the first solo gig where I decided this would be a good opportunity to build a set around this new sound. So, with Ross onboard (I was already gigging with Ultan O’Brien) we just jammed things out over the course of a couple of months, with me describing the styles I was into, the emotion of where the song was at and how I wanted the song to develop. I already had guitar arrangements for them. So, I’d say to Chaney for example, ‘I want this to be a bed of synthy drones to lift up the arrangement with the guitar, fiddle and voice into a wider, different space.’ Through those conversations and the fact that we had the show lined up, it happened fairly quickly. We realised that even though we weren’t from the same genre of music, we worked well together immediately.”

Free-floating in this newfound space, Ross’ Tascam tape deck, took them to further heights, as Flynn revealed: “Say if you’re playing a harmonium or an organ, how you change the sound is likely by just changing the note. But the power of the Tascam is you can subtly mix it as you go, just using it as a desk and also putting it through pedals. It’s very slow-moving, but it eventually develops into something else other than what it started at. There’s a journey in just the drone alone. Live, it’s not going to be the exact same every time, but it’s not going to be far off. That’s another part of the beauty of it; he’s playing as he goes. He’s being fed whatever tape’s playing, and that could be subtly different, and he could be at a different part of the tape each time.”

This sense of deep exploration is most impressively displayed in the three songs that make up Bring Me Home. Flynn explains how these songs found each other:

“That’s a journey. I was listening to this fella, a settled traveller called Paddy Quilligan on the University College Dublin archive. There’s a recording from the 70s made in Limerick, it’s just the one track and he sings that song Bring Me Home To North Kerry. I thought it was just amazing. It’s only short, two verses long, but I was singing it for a while. Anyway, then I found this track on an old Alan Lomax recording that was I Would Not Live Always; a fiddle piece that’s a slow air and then right at the end, this Clarence Ferrill sings just those two lines. I found it really interesting. I thought that’s a similar vibe and message to the other song. In Irish music if you’re playing instrumental tunes – reels or jigs – usually you play a set of them. You’d very rarely do that with songs. So, I decided to put the two together and build the piece around that.”

Jenkins’ interpretation of the title track nails it: “There’s a sort of architecture to that arrangement that’s really exciting. It’s like when you see a beautiful building. It’s sort of visceral like how it brings you through the storm section,” he goes on to admit he’d never have thought of constructing it like that himself. So, was Flynn surprised by the shape it took?

“Absolutely, it was definitely an exploration from the get-go. My guitar arrangement starts very slow and sombre, but when it hits that second song, it gets bigger, more energetic, with me just repeating those words over and over. When we were doing that Body & Soul gig I mentioned, I wanted it to build up and up with the electronics around it until it became really messy like an actual storm. So, Ross came back with a load of different drones, arpeggiated synth stuff on the tape, and we put the drum behind it; it worked perfectly.

Then the third track was just the two of us improvising in the studio after just finishing recording the other two. The basis of it took just four minutes. That was going to be it. It was only later on that I thought it might be interesting to reference the first track in the piece with the Irish version. Instead of singing, just have a recitation, real spooky, manipulating the vocals in the studio as we went. We did that a little bit, and we put it in different places. But when it came down to it, Saileog Ní Ceannabháin recited the piece so beautifully; we thought we’d just leave it as is. I thought it was very powerful.”

As our premiere of Lovely Joan goes to show, this spontaneity isn’t reserved solely for the studio; Flynn intends their live shows to chase these sounds and atmospheres even further:

“Basically, live sets these days, I like to play the song and then if there’s space for just jamming around with the chord progression after the song, we do that. It’s just a fair bit of craic, laying into a bit of an improv session. I enjoy it; we just lash off on something. As long as it’s not over the top, it’s still bringing you on that journey and you can still keep the vibe of that piece going, then I’m up for doing it. I wouldn’t force it. There’s definitely songs where I’m like once it’s over, it’s over.”

Whether it’s in reference to the record’s sequencing, the distance a tune has travelled or even the deviation of Chaney’s drone, our conversation often circles back to the topic of journeys, perhaps to be expected from the self-proclaimed ‘mild rover’ and ‘time traveller’ himself. And now, with the rapturous return of live music, it looks like Flynn’s safe to hit the road once again. Last week he made his way down to Cork with Ultan and Eoghan Ó Ceannabháin for his first proper show in eighteen months (just the two dates, but Flynn still insists it’s a tour); on the 18th August, he’ll join the Mac Gloinn brothers aboard a barge for Ye Vagabonds’ ‘All Boats Rise’ project (keep an eye out for their exclusive posts on Folk Radio – the first will be later today); then, come the end of the month he heads back out in support of Aoife Nessa Frances.

Then as if that’s not enticing enough, there’s also plans for another Skipper’s Alley record next year, and John has a flute and fiddle album in the works with Cathal Caufield too. “Oh, there’ll be no shortage of tunes,” Flynn chuckles reassuringly. Here’s to that and plenty more years of a-roving to boot.

John Francis Flynn’s I Would Not Live Always is out on River Lea (30 July 2021).

Order via: https://store.roughtraderecords.com/products/john-francis-flynn-i-would-not-live-always

Follow John Francis Flynn: Facebook | Twitter

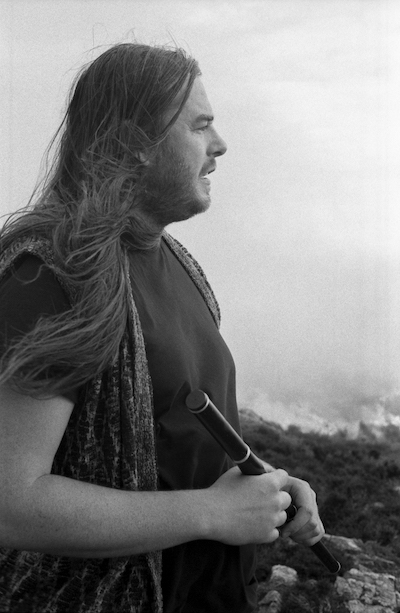

Photo Credit: John Lyons