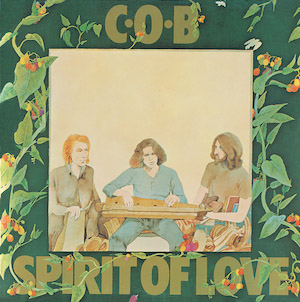

C.O.B. – Spirit of Love

Bread and Wine Records/EastCentral One – 23 April 2021

Some people just never push themselves and that’s why they are not as famous as they could be. Is this an exam question? Should that statement be followed by ‘Discuss’? Well, no, I was just reflecting on musicians that have been forward in going backward, and I think that if I were to choose a prime example, it would have to be Clive Palmer. Clive left school at 15, fled from London to Edinburgh, fell in with the booming folk scene of Bert Jansch and the like and eventually teamed up with Mike Heron and Robin Williamson, forming the first incarnation of The Incredible String Band. They record an album, look like they could take off, and then Clive did just that, took off to Afghanistan telling the band that they can carry on without him – and that they could use his songs, he wasn’t worried about the copyright.

Back from his travels, Clive moves to Cornwall, a place he has visited often, and takes up residence in a caravan, and with John Bidwell, Mick Bennett and a packet of Digestives forms Clive’s Original Band – C.O.B. A bit of a sprint through that part of his life – there are a number of books that can give you chapter and verse – and we come to the recording of C.O.B.’s first album, Spirit of Love. Released in 1971, a fiftieth-anniversary reissue is available from April 23rd this year.

The thing that strikes me so clearly, revisiting this album after several years of neglecting it, and starting with the title track, is how near yet how far it is from the Incredible String Band. The simplicity of rhythm and rhyme, the catchy tunes and the clear words are common in both bands, but the COB album is somehow sparser, and the balance between the words and the tunes much more in favour of the former; a good melody to carry the rhyme but the rhyme must win out.

If you scratch the surface of this album, there is a lot of stuff relating to the changing times in music, yet there is also an overall sense of originality. Clive himself tended to avoid listening to other music, to allow his own tunes to come out uninfluenced, but it must have been difficult to ignore what was going on even in Cornwall in the late ’60s where there was quite a burgeoning scene. Simply put, anything goes and we hear Banjo Land, originally from an album of the same name recorded a few years beforehand but not seeing the light of day until the new century. Although the sleeve notes say that both Clive and John Bidwell are playing banjo (Clive’s original instrument), there is definitely a guitar in the mix as well. The traditional tune, almost an intermission piece, though was not at the end of the first side of the original LP, comes out of the sounds of children playing, of birds singing, and of the sea.

Wade in The Water is sung by Clive, John and Mick a cappella other than the drum of the producer, Ralph McTell. Ralph got happily drawn into the recording process with what started as a labour of love for him. He had admired Clive’s work in the ISB and with Wizz Jones but the time in the studio soon turned into a challenge to control a ‘loose and undisciplined’ band, eventually becoming the most difficult recording he had ever been involved with. But it works.

The first track on the second side is Scranky Black Farmer, a traditional song with Scot’s dialect, but presented here through a megaphone (of the Walton’s Façade type) and with an almost at times clipped English accent. A bit of a smile amongst quite a bit of ennui. And the ennui is rarely clearer than in Evening Air:

All the dreams that I had forgotten

They come again, to fade as soon

And

Because I loved you, because I wanted

Because I didn’t want to lose

I hung suspended in dark suspicion

Unable to reach as far as you

But, despite the ennui, here is another style, a hark back to an earlier musical age, aided by John Bidwell on recorder and dulcitar. The dulcitar was John’s invention following an accident involving his dulcimer being left on the car roof when driven off. The sound is part dulcimer, part sitar and is so timeless that you wonder why one had not been invented much earlier, even if chicken wire was an essential part of the original.

The open air, nature and the cosmos are all part of COBs universe. The golden apples and the red sun’s dawn of Evening Air, the morning’s perfectness of The Serpent’s Kiss as the cycle of life continues to turn, and Sweet Slavery’s Lazy girl’s hair ablaze as Autumn evening skies, all bring a wide bucolic vista to the songs.

Finally we come to When He Came Home, perhaps a fitting song for Clive, certainly for many of us today

When he came home

All the troubles

Of the world were at his feet

And his poor heart was aching

As he gazed along the street

And nothing was quite the same

As he dreamt that it would be

Visions of the years he spent

With those who cared before

Arose and fell before him

Like the ever-open door

And nothing was quite the same

As he dreamt that it would be

But the song finishes and the tune continues, the closing credits without the words. You know you have reached the end and nothing will be as you have dreamt it. But not to worry, as we are played out by guitar, Indian hand organ, bongos and cello, as good a 60’s acid-folk set of instruments as you could wish for. Whatever we dreamt, it was all about singing songs of love and truth, like water running free. For an imperfect perfect glimpse into the past, and for its paradoxical timeless quality, succumb to the spirit of love, either, like me, again, or for many of you, for the first time. Excellent – and pass me that joss stick.

Order via Amazon CD/Vinyl

Interview by Rupert White summer 2010 as part of research for ‘Folk in Cornwall: Music and Musicians of the Sixties Folk Revival’. An excellent book, now available on Kindle as well here.