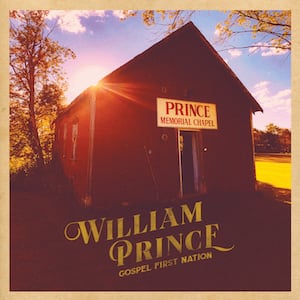

William Prince – Gospel First Nation

Glassnote/Six Shooter – Out Now

Considering the nature of this second release of 2020 from the Manitoban country-folk artist William Prince, while considering myself a spiritual person I should declare that I’m in no way religious, nor have I ever been. Nevertheless, I’m interested in religion as a societal concept; in genuine awe of sacral architecture; intrigued by religious leaders as figures in history and, from my perspective as a melomaniac I enjoy the emotional contagion aspects of some faith-based music, including gospel, Qawwali, and plainsong. I say this because in approaching an album bearing lyrics that, unless expressing a relatable universality, I cannot intrinsically connect to, I feel that as an existing fan of his music it’s of greater respect to the artist, and Folk Radio UK readers, to here state my objectivity towards Gospel First Nation’s lyrical content in order to present an equitable assessment.

In addition to this, as a born-and-raised Englishman of relatively recent Canadian citizenship (9 years), I’m acutely aware that I’m effectively a tenant living on stolen land. Learning all the time about my new country’s history, the British colonization period being particularly dark, I’ve naturally been horrified to learn of the central role the Christian church has played, especially through the abhorrent residential school system, in the genocidal westernization of Canada’s Indigenous peoples. (I touched upon a harrowing localized aspect of this colonialism when reviewing Dirty Grace’s Coals & Crows for FRUK in 2015.) With these facts in mind, I hope it’s understandable that I greeted the announcement of this release – of overtly Christian material, by a Peguis First Nations artist – with a raised eyebrow of curiosity.

While the annual dedicated Indigenous Music Awards in Canada includes a gospel category, First Nations gospel acts seem to be few and far between. I’m not suggesting that First Nations Christians are in themselves a rarity, rather that I’ve not encountered an Indigenous release such as this before. While this is a country-gospel album, so not gospel music as it may be widely understood, on paper, Gospel First Nation seems to be a paradoxical release with much to unpackage. Assisting me somewhat with that process, Prince has issued an artist’s statement with the album providing background, context, and what transpires to be an on-point topical motivation for putting this collection of songs together. Albeit excerpted here, within that eloquent statement Prince says:

“With regard to First Nations communities, gospel music and Christianity are stigmatic as a tool of colonization and assimilation… As a young person, I never fully understood why the divide between cultural and Christian First Nations people existed. In actuality, the very singing of these songs and belief in a Lord and Saviour is the success of a plan to extinguish Indian identity. This album is an amalgamation of two realms… I learned how to play music through old hymns during peoples’ time of grief. My dad and I were often tasked with singing at wake services and funerals… Having numerous musicians show up to ‘join the band’ was common and left a lasting impression of how music can be communal and healing. We are living through an age of grief – grieving our lives, routines, and families at the hand of a pandemic. Through my adjustment, I found myself singing songs that made me feel better. I found myself wishing to return to this place of comfort amidst all the chaos…”

Like others of his forebears, Prince’s father, Edward, was a preacher, so a Christian upbringing for William was predetermined. Edward recorded three albums, selling copies from the boot of his car when taking his message to First Nations communities in Northern Manitoba. One of Prince Sr.’s songs, This One I Know, is beautifully covered by his son here, alongside three originals, gospel standards, and songs learned as a youngster when accompanying his father at events like the aforementioned wakes and funerals. Of the original trio of songs, two were written following the release of the gorgeous Reliever – Prince’s first album of this tumultuous year – and the other, When Jesus Needs an Angel, he penned at just 14 years-old.

As with his first two records Gospel First Nation was recorded at The Song Shop in Winnipeg, and produced by Scott Nolan, who produced Prince’s 2015 debut, Earthly Days, and co-produced Reliever, so it’s an ongoing fruitful collaboration. Nolan also contributes instrumentally, bringing guitars, vibraphone, and backing vocals to the table. Joining the core pair on this record are drummer Christian ‘Coco’ Dugas (The Duhks / Stephen Fearing / The Wailin’ Jennys), bassist Julian Bradford (Crooked Brothers /Jenny Berkel / Carly Dow), keyboard player Kevin McLean (SubCity Dwellers / The Paperbacks), veteran champion old-timey fiddler Patti Kusturok, pedal steel player Eric Lemoine (The F-Holes / Little Miss Higgins) and, with an extensive background in musical theatre, session backing vocalist Alyshia-Grace Hobday.

Behind Prince’s gently strummed acoustic guitar and velvety baritone voice, sonically speaking this talented ensemble has crafted a fine, nicely paced country record, albeit with downtempo outnumbering uptempo songs eight to two. Overall, despite melancholy moments it’s easy on the ear, light and airy, and extremely lovely, putting me in mind of the mood of Randy Travis’ classic 1986 debut, Storms of Life.

The title track opens the album, and is followed by Higher Power. Built on the same theme of seeking salvation from sin as The Louvin Brothers’ classic, There’s a Higher Power, this song was penned by Bob Norman, a Meadow Lake, Saskatchewan, First Nations gentleman, and concerns the narrator’s deliverance from alcoholism. Next comes When He Cometh, written in 1856 by George Frederick Root and Pastor William Orcutt Cushing, specifically for the children of the latter’s church’s Sunday school to sing. In Prince and company’s hands it’s an upbeat country-gospel shuffler showcasing Kustorok’s fiddle.

Composed by married songwriting team Alan and Marilyn Bergman, and Henry Mancini, All His Children is a a paean to humankind and the natural wonders of divine creation. Serving as the theme tune to the Paul Newman-directed 1971 movie Sometimes a Great Notion, it’s particularly notable for a version by Charley Pride, but Prince’s sparer version is a tad slower to lend greater elegance. Up next, and a frankly heartbreaking song of loss and mourning, Prince’s teenage composition, When Jesus Needs an Angel, is an instant country-gospel classic, performed with soul and gravitas. Following that, and previously recorded scores of times by acts mainly in the country, folk and, obviously, gospel arenas, the traditional Just a Closer Walk with Thee is here given a loose, sprawling treatment that plods languidly and pleasantly on for just over five minutes.

In terms of prolificacy, Charles Hutchinson Gabriel was a gospel song and tune-writing colossus, responsible for between 7,000 and 8,000 compositions, one of which – Send the Light – was written in the late 19th century and, I believe – but don’t quote me on it – lent a contemporary hymnal piano arrangement by David Smither. Prince’s rendition is a spirited clap-along in true gospel tradition, then is followed by a slow waltz, entitled Does Jesus Care? This was written by Philadelphian Methodists Franklin Ellsworth Graeff, a preacher, and Joseph Lincoln Hall, well known in his day as a gospel songwriter and publisher, as well as a composer and arranger of classical church music.

Edward Prince’s This One I Know is Gospel First Nation’s penultimate track, and what a fine tribute his son pays him with a heartfelt performance; he’d surely be beaming with pride in the afterworld concerning the closing Love Don’t Ever Say Goodbye, a solo Prince performance and further evidence that his son is rapidly establishing his rightful place among Canada’s greatest ever folk singer-songwriters.

On the one hand, on the outside looking in it’s difficult for me to fully grasp the intricacies of this album, presenting as it does the dichotomy of an artist passionately performing songs either directly emanating from or inspired by a particular belief system, a tenet of which was to eradicate all traces of his people’s culture and identity. As one still learning and striving to understand this intersection, I feel it apt to quote from Gospel First Nation’s press release, which articulates what lies at the heart of this album way better than I can, being that it’s “a statement of startling, radical magnitude,” and “an act of building a bridge between worlds at-odds, as a way to find harmony in conflicting, complex truths.”

On the other hand, there’s also a great simplicity to this deeply personal record. As the pandemic rages on, and one awful way or another this hellscape of a year delivers stress upon stress, every single one of us is turning to those things that alleviate the pressure, bringing solace and healing, be it immersing ourselves more than ever before in family, community, art, culture, music, or whatever happens to be your own coping mechanism. I know I have, especially when it comes to music. As he says himself, William Prince is finding some peace by singing the songs that assuage him, “wishing to return to this place of comfort amidst all the chaos.” This top of mind, regardless of the fact that as an atheist I cannot emotionally plug into much of the album’s lyrical content, speaking simply as a human being Gospel First Nation is probably the most relatable record I’ve heard all year.

Gospel First Nation is available now on CD, vinyl, and digital download.

WEBSITE: https://www.williamprincemusic.com/

FACEBOOK: https://www.facebook.com/williamprince

Photo Credit: Joey Senft