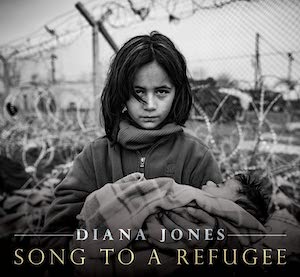

Diana Jones – Song To A Refugee

Proper Records – Out Now

Nina Simone famously said that it was ‘an artist’s duty to reflect the times’, which of course she did in her inimitable and formidable way. Her own career, and that of many others, illustrates that it isn’t possible for most to maintain a consistent focus on the issues of the day, but what Diana Jones new album, Song To A Refugee, shows us is just how powerful the result can be when an artist is deeply moved to respond to the way some human beings are being demonised and mistreated.

Song To A Refugee shines a light on the blatant scapegoating of refugees and asylum seekers, telling their stories, many based on real-life events, from a wide range of individual and emotional perspectives, primarily, but not exclusively in the context of the treatment of people on the U.S.A.’s southern border. The relevance on this side of the Atlantic is obvious, with politicians describing asylum seekers as criminals, and considering plans to transport them to an island 4,000 miles away, the album represents a call for compassion, in words and in deeds.

I confess that I wasn’t familiar with Diana Jones before coming across Song To A Refugee. Readers will be familiar with the particular pleasure that comes with ‘discovering’ an artist for the first time whose music strongly resonates with you. Even better if they have a pile of previous albums – Jones made five albums before this one – three of which have been covered by Folk Radio UK (including an interview), that you can look forward to exploring through the coming, uncertain and unusual winter.

This CD arrived at the same time as Michael Rosen’s, highly recommended, new book (with haunting drawings by Quentin Blake), ‘One the move: Poems About Migration’. In the introduction, he reminds us that not only did we all originate from somewhere else but that the story of our own relatives’ migration will most likely resemble that of today’s migrants. Most of my own great, great Grandparents left Ireland around the time of the great famine and emigrated to the North-West of England to seek a safer life. With Song To A Refugee Diana Jones is also saying unequivocally that migrants are not ‘others’, they could be us, and she gives voice to the reality of their lives, and their deaths.

A stark waltz melody picked out on guitar sets the tone for El Chaparral, the opening track. At once we are pulled into a similarly stark story about a child arriving alone at the El Chaparral port of entry at the Mexico/California border, having fled a war-torn central American country with his parents. The opening lines tell it how it is: “How can it be that I reach the last border alone; my mother my father lost to the side of the road”. A quiet accordion, played by Will Holshouser, weaves its way under the song, playing the tune through before the final verse, very effectively evoking the Mexican border feel. The shocking reality is laid bare: “In El Chaparral the children slept out in the rain”. I found myself listening intently to every single word in a way that rarely happens; there is instantly something fully captivating about Jones’s singing.

Jones tells a number of stories from the perspective of women, as mothers, as sisters and those forced into marriage. I Wait For You tells the story of a Sudanese woman who was sold by her father, aged only thirteen, to a ‘husband’. The woman later decided to leave her three children behind hoping to send for them after seeking asylum in the UK: “You have all my heart while we are apart, and someday I hope you understand.” The uncertainty that faces asylum seekers is captured in the lines: “no work no pride, some wait for years to find what England will decide and I wait for you.” It’s one of three tracks benefiting from a sprinkling of Richard Thompson contributions, with just a bar or two of Thompson-esque guitar interweaved with David Mansfield’s mandolin, and wonderful harmony singing from him, in a notably high register on the chorus, adding to the sense of human anguish on a distinctively memorable tune.

The title track on Song To A Refugee is a counter to the demonisation of refugees and asylum seekers by Governments and the press across the world. David Mansfield’s violin carries the melody beautifully, gently augmenting the insightful purpose of the song. It could of course even be us:

“Song to a refugee song to us all

none of us know where our footsteps will fall

and what will become of the place that we love

the place that we think of as home”

On We Believe You, Jones brings in a choir of well-known fellow singers including Steve Earle, Richard Thompson, Peggy Seeger on a song which refutes the lie of the bogus asylum seeker. The vocal arrangement is wonderfully effective, amplifying the shared sense of ‘believing’, and reinforcing the lyrical shift to the collective half-way through, from a chorus of ‘I believe you’, to a chorus of “We believe you”. The song was inspired by Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez’s visit to a US border detention centre last summer, and subsequent testimony in Washington D.C. She said: “I believed the women,” when speaking about the reasons why they left their homes to seek asylum and the terrible conditions within the detention centre.

Not all the songs on Song To A Refugee are as direct or as literal. The later part of the song cycle is more oblique, more reflective. For Love Song To A Bird Jones, “thought of being in a boat like so many that set off between Egypt and Lesbos, Greece and imagined what it would be like to see a bird fly over.” David Mansfield’s soaring violin brings to mind the flight of the bird, echoing the contrast in the song between the freedom of the bird and heartbreak of the person in the boat:

“If we could rise so swift and high

and touch down like the angels

with no thought of where we land

no country and no borders”

The final song, The Last Words, is about the loss that comes with death. Unsurprisingly a more brooding song, it is another example of Jones’s very fine lyrics, with a degree of solemnity emphasised by the addition of sparse piano from Glenn Patscha, closely following Jones’s wistful, affecting singing.

“Glory wealth and power

were never ours to find

only love’s enduring vow

and the ones we leave behind”

The Last Words could be heard as recognising the many refugees and asylum seekers that have died in their pursuit of a safer life, but Jones has suggested that she is contemplating the universality of an experience that we can probably all relate to: “The crisis of people worldwide seeking safety and home caused me to think of that which is essential in life, and how it can become more clear at the end of life.”

The arrangements on Song To A Refugee are unfussy, doing only what is needed to support the vocal and enrich the mood in the brief instrumental breaks. The result is that the listener’s attention is drawn fully to, and held by, the singing and the words.

Diana Jones song writing offers real clarity of meaning across the range the human stories she shares, engendering empathy with people who are forced to flee all kinds of danger, only to face walls, fences and hostility. Her melodies are very well matched to her lyrics, often sounding like traditional tunes, and in the process lending appropriate gravitas to the stories we are listening to. The whole stops you in your tracks, and Jones brings, in both words and vocal delivery, a consistent dignity, that conveys the deep compassion at the heart of this album for ‘the times’.

The parallels between Song To A Refugee and Michael Rosen’s book are also there in asking us to do more than only listen and empathise. The final poem in Rosen’s book is titled Today, and he is asking us to ‘do something today’: “You can’t do something yesterday; You can’t do something tomorrow; You can only do something today.” Jones, invites a spokesperson from a local refugee organisation to speak during the interval at her gigs, and says that: “I’ve watched people get involved immediately.” In the sleeve notes she asks people to donate to national or local refugee organisations. The quote from novelist Dina Nayeri, which Jones includes in sleeve notes, sums up very well why she made this exceptional album: “It is the obligation of very person born in a safer room to open the door when someone in danger knocks.”