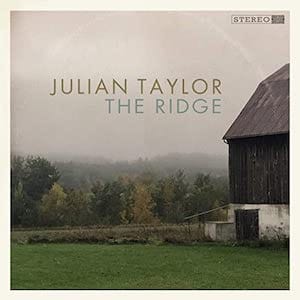

Julian Taylor – The Ridge

Howling Turtle – 19 June 2020

A staple of the Toronto scene, Julian Taylor makes a strong bid to expand his audience with this eight-track collection that, all drawn from personal experiences, sees him return to solo acoustic roots form (albeit with various backing musicians, including cousins Barry and Gene Diabo as rhythm section) after three studio albums by the more R&B-oriented Julian Taylor Band.

Reflective and intimate, it opens with the title track, a rolling rhythm, shuffling drums and Burke Carroll’s pedal steel coloured straightforward reminiscence of his childhood innocence when he and his sister spent time with their late grandfather and step-grandmother on their farm in Maple Ridge, British Columbia, catching frogs and cleaning out the horses. Miranda Mulholland’s fiddle to the fore, the song also contrasts life then with life there now, long after they sold up and passed away, that it “never ends”.

A shimmering waterfall of pedal steel notes underpins the quietly sung Human Race, a song about a close relative who’s suffered with a life of from mental illnesses and learning disabilities but honouring the fortitude with which they’ve dealt with them, extending their experiences to his own challenges in life as someone of part Mohawk, part West Indian heritage as he sings “we all feel out of place in the human race”.

The theme spills over into It’s Not Enough, Derek Downham’s piano accompanying the slow strummed, country-soul number about, as he puts it “living with our own inadequacies and the admission that nothing is perfect and never will be”, an acknowledgement that makes us stronger rather than weaker as we strive to care for those close to us (“I’m going to pick you up before you run”), the song stemming from how a relationship survived being battered against the rocks.

Again built around piano, guitar and caressing strings, the slow waltz Over The Moon addresses love on different levels, embracing friendship, romance, lust, unread, unsent letters and the belief that we’re being watched over by our ancestors as he sings of “debts that I will take with me to my grave”. He picks up the tempo for the percussive chug of Ballad of the Young Troubadour, a wordless chorus recollection of his formative musical years, a teenage summer road trip across America by hitching, trains and Greyhound buses, busking as he went, looking back on those days when in doubt, but remembering how “reality wasn’t cracked up to be what it was meant” and that not everyone got out alive, recalling how “each inch of pavement has a story to tell”.

Again soulfully crooned, a simple love song on which those Gordon Lightfoot and James Taylor comparisons can be heard, Be With You was written during a workshop at a camp for children living with and affected by cancer, the simply picked number complemented by piano waves capturing the positivity and appreciation of life during struggle that he witnessed while there.

The most uptempo track on the album, co-written with the poet Robert Priest, the sunnily infectious Love Enough marries undulating Buddy Hollyish percussion with a Texicana feel that calls The Mavericks, and especially Raul Malo’s Orbisonesque -tones, to mind. It ends on a distinctively contrasting note with a hypnotic drum rhythm (that reminds me of the Zombies’ Time of the Season) and loose-limbed bass for the spoken Desiderata-styled (“the great spirit of the universe gathers unformed thoughts and unfolds them into their proper channels”) Ola, Let’s Dance, this time embracing his maternal grandparents who acrimoniously divorced when his mother was still a little girl, his grandmother (the Ola of the title) moving to Toronto and his grandfather to Maple Ridge where he remarried. Going through their belongings after they both passed, Taylor found the poem written by his grandfather that now forms the lyric while the tribal rhythm music takes its cue from how Ola taught African dance, reminding us that “we are because it is” and calls on us to “recognise and accept freely the peace, the harmony, the love and joy” and “open our eyes and let it be” before ending on the repeated title invitation.

Open and heartfelt, personal yet universal, the only complaint is that it’s only eight tracks long when I could have happily sat through twice that.