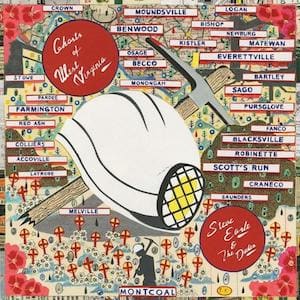

Steve Earle & The Dukes – Ghosts of West Virginia

Steve Earle & The Dukes – Ghosts of West Virginia

New West Records – 22 May 2020

While not a concept album as such, Steve Earle’s 17th studio album draws upon 2010’s Upper Big Branch coal mine explosion which, killing 29 miners, was one of the worst mining disasters in American history and revealed hundreds of safety violations, to provide a springboard for a collection of songs about the role of coal mining in Appalachia, seven of which he performed live as part of Coal Country, a stage play about the explosion which had a brief run in New York in March.

Featuring Jeff Hill who stepped in when longtime bassist Charles Kelley Looney passed just prior to the recordings, it opens with Heaven Ain’t Goin’ Nowhere, a call and response a capella spiritual come work song with Earle’s gravelly vocal in fine, throaty form. Eleanor Whitmore’s fiddle and Rick Ray Jackson’s pedal steel prominent, the band strike up on the train rolling rhythm and brushed drums shuffling Union, God and Country, recounting how coal dust runs in the veins of those born in West Virginia and of how unionisation came about in response to the conditions and hours under which the mining company made their employees work, the pittance they received being recycled down at the company store.

Earle on banjo, Devil Put The Coal In The Ground returns to a two-step work song rhythm, the title leading the chorus refrain punctuating a song about the men going into the mines every day knowing “black lung’ll kill me someday”, but carrying a sense of pride as they chant “The good lord gimme two hands/Says is you an animal or is you a man”.

While he was an African-American railroad worker rather than a miner, one of West Virginia’s most notable folk heroes was John Henry, after whom Earle named his youngest son, and who, along with his trusty hammer, appears here in John Henry Was A Steel Drivin’ Man, a bouncy, bluegrassy number which, after burying him in his grave, turns to the way in which the arrival of new industrial technology signalled the end to a way of life.

Returning to a simple fingerpicked guitar backdrop, Time Is Never On Our Side is a reflective ballad about the hardscrabble life of those in West Virginian, one of the country’s poorest states, where “sometimes days crawl and others fly”, and the folk “take whatever fate provides”, knowing that “good things come to those that wait” is just a lie.

Set to a circling chiming guitar and bluesy rhythm, It’s About Blood addresses the disaster directly, the song ending with Earle intoning the names of the dead while, in-between, he sings of how the dignity and surety of the working man has changed in the face “fiscal reality, profit and loss” and how “just getting by is a miracle”.

Earle steps back and lets Whitmore take the spotlight to sing the fingerpicked acoustic show closer If I Could See Your Face Again, a country ballad in vintage Emmylou manner with keening pedal steel as, extending the connection to the tragedy, she tears the heart apart as she sings “if I could see your face again/Black with coal until you grin/Cuts like sunshine through the shadow of the mountain/I’d drop everything and run/Like I know I shoulda done/Every time you came home to me in the evenin’”.

Having referenced it earlier, the mandolin and fiddle arrangement joined by drums for a steady, rhythmic hammering stomp, Black Lung, the first of the numbers not from the show, picks up on Coalworkers’ Pneumoconiosis, an often terminal disease caused by long-term exposure to coal dust (“every breath I take like a 12-round fight”), but then, the narrator wryly observes “half a life is better than nothin’ at all”. It’s followed by another tangential number, the rockabilly styled Fastest Man Alive with Hill on acoustic bass, a tribute to another West Virginia hero, test pilot Charles Elwood Yeager, the first pilot to break the sound barrier, here told in the first person.

It ends back down in The Mine, another sparse acoustic county ballad with a simple chord progression, Earle at his throatiest and with underlying Springsteen hints as he sings in the world-weary voice of a man facing hard times, pawning his wife’s wedding ring to try and make ends meet, but promising things will get better because he’s far better off brother’s going to pull some strings and “it’ll only be a matter of time/Till I get myself together and my brother gets me on at the mine”. There’s something in the voice that tells you even he knows this is a pipe dream or, worse, he’s fated to be one of the twenty-nine. The echoes of these ghosts haunt long after the album ends.

Photo Credit: Jacob Blickenstaff