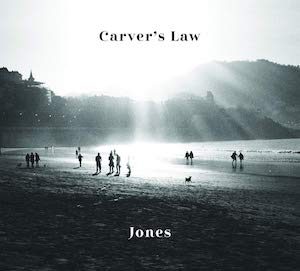

Jones – Carver’s Law

Jones – Carver’s Law

Meme Records – 12 July 2019

Stay with me here, there are tangents.

In 1961, US sports columnist Murray Olderman, covering a particularly attritional game of American Football between the New York Giants and the Philadelphia Eagles, opined that the Giants had ‘left it all out on the field.’ The phrase, now a cliche, is regularly repeated to this day both in sport and elsewhere, having come to represent any situation where the protagonist cannot possibly give more of themselves. They are spent, hollowed out in the pursuit of their excellence.

There’s a literary take on Olderman’s infamous comment. Raymond Carver, he of the devastatingly acerbic short stories and troubled personal life had, in his later years, a propensity to view a good piece of work as the result of giving his all in each moment. In doing so, he allowed, every day, space for the new.

(Trevor) Jones, fifty percent of Miracle Mile (the best band in the UK that no-one’s heard of, © all those of us who have) has in recent years concentrated on a solo career, albeit one that closely involves Miracle Mile’s other fifty percent, Marcus Cliffe, in multi-instrumental backing and crisp production. Following on from 2015’s Happy Blue, Jones’s 5th album, Carver’s Law is no exception.

Carver has been a regular in Jones’s lyrics. In ‘Coleman’s’, reference is made to a Vanity Fair piece by Tom Jenks, where one evening Carver was so hungry he refused to wait until he arrived at his restaurant of choice and instead pined after every fast food joint on the way. Luckily for both us and him, his will held, and forever after a choice turn of phrase or a well-honed story was considered worthy of having gone ‘all the way to Coleman’s’.

Named after Ray’s penchant for perfection, Jones has indeed ‘left it all out on the field’, or, in musical parlance, graced every digital space with nothing less than every singer-songwriting chop he’s got. If you’re au fait with his repertoire, initial impressions may suggest a subtly incremental move away from acoustic guitar to piano-based melodies, but the hallmarks of his work remain in place. Here is further proof that sometimes its what you don’t say that matters. A distillation then, a refinement, a wee small hours of the morning piercing of the ever-increasing noise that surrounds us from the moment we wake to our troubled hours of restless sleep.

Why re-write rules that don’t need to be broken?

What Jones has done is dig deeper. The darkest recesses of his psyche are mercilessly mined. When the nuggets of unassailable truth and beauty are brought to the surface, they leave the listener a little wiser, but wounded by the searing honesty. There are numerous allusions to the demon drink (Drinking Alone), dark nights of self-analysis (Blackshore) and the excoriating bleed of heartbreak that lies below the surface of long-term relationships (Have A Sunset On Me and What’ll I Do?).

And yet… and yet, as ever with Jones, his Holy Trinity of hope, heart (so much heart) and forgiveness act as lyrical lifeguards, seeing you safe to the shore when the lighthouse batteries are out.

Quite how an artist regroups after an effort like this is anyone’s guess. I’ve not heard anything as beautifully intense or personal since Bon Iver’s ‘For Emma, Forever Ago’. Murray Olderman, and Carver, would be proud.

Carver’s Law is out now.