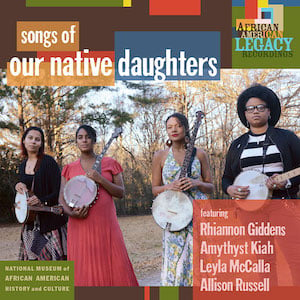

Our Native Daughters (Rhiannon Giddens, Amythyst Kiah, Leyla McCalla, Allison Russell) – Songs Of Our Native Daughters

Our Native Daughters (Rhiannon Giddens, Amythyst Kiah, Leyla McCalla, Allison Russell) – Songs Of Our Native Daughters

Smithsonian Folkways – 22 February 2019

There were a lot of highpoints at last year’s Cambridge Folk Festival curated by Rhiannon Giddens, but there was something particularly magical the final evening when of most of the acts that Giddens had invited to perform at the Festival came together on one stage. Those present that night included three of the four black women artists – Giddens, Amythyst Kiah and Alison Russell (Birds of Chicago and Po’ Girl) – who feature, together with Giddens former Carolina Chocolate Drops fellow band member Leyla McCalla, on the remarkable album Songs of Our Native Daughters (the title inspired by James Baldwin’s Notes of a Native Son).

Black Myself, one of the standout moments from that performance and the opening track of the album, is an immediately compelling song, sung in the style of the very best female southern soul singers by Amythyst Kiah. Kiah also wrote the song, about which she says: “the refrain and title of this song are intended to be an anthem for those who have been alienated and othered because of the color of their skin.” Having, in great numbers, joined in harmoniously with a gospel song which was only being sung on stage to check the sound levels, the almost entirely white audience proceeded to join in with the chorus of Black Myself. It seemed both an instinctive response from an audience that takes any and every opportunity to partake, and an evocation of real solidarity expressed through singing along.

Like that live experience, once you grasp the vital purpose at the heart of this ground-breaking project, it’s hard not to feel a stronger sense of respect for the struggles, resistance and resilience of black American women.

The track Barbados illustrates how well this project excels at what Giddens describes in the CD booklet as ‘taking historical words and notions and observations about slavery and making art with them’. Coming across a quote from a poem by William Cowper that read: “I admit I am sickened at the purchase of slaves…but I must be mum, for how could we do without sugar or rum?” on a trip to the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington, DC. was for Giddens a key inspiration for the project. She writes in her introduction: “Not knowing then that the author was most likely an abolitionist and had written the words in deadly earnest satire, I was massively struck by the sentiment …I took a picture with my iPhone, and I remember immediately texting the image to my co-producer Dirk Powell, saying this needs to be a song.”

As it turned out on the album, Giddens recites rather than sings the poem, and does so lyrically, with just the right amount of parody. This provides one bookend to her lilting, accompanied by banjo, guitar and percussion, of an evocative, melancholy tune ‘said to be the first western notation of New World enslaved music, … put down by D. W. Dickson in Barbados in the 18th century’. The other bookend is by a poem written as a modern response to the Cowper poem by co-producer Dirk Powell about how slavery today underpins the production of many of the things we have come to rely on: ” What—give up our tablets, our laptops and phones?’

Once the four protagonists were ensconced in Dirk Powell’s Cypress House Studio in Louisiana (described by Giddens as ‘a special space and is a player in any recording that takes place there’), the project blossomed out as the confluence of participants and place led to an unintended burst of on the spot songwriting in various combinations. As Giddens says: “Gathering a group of fellow black female artists who had and have a lot to say, made it both highly collaborative and deeply personal to me. It felt like there were things we had been waiting to say our whole lives in our art; and to be able to say them in the presence of our sisters-in-song was sweet, indeed. I see this album as a part of a larger movement to reclaim the black female history of this country.” Moon Meets The Sun, the first song written during the sessions (by Giddens, Russell and Kiah), exemplifies the strength of the collective as all three sing the chorus but take it in turns to sing the verses, in a song about the resilience of slaves in the face all the horrors they faced: ‘we’ll survive this, you can’t stop us and we’re dancing’.

I Knew I could Fly, with banjo, guitar and mandolin, sounds both old and familiar but was co-written by McCalla and Russell, about discrimination and its effects. As they were writing it, they realised that the words illuminate the story of a 20th-century black woman blues guitarist Etta Baker, who barely performed in public after she got married in 1936 and then gave birth to nine children. She said that her husband didn’t want her “to be gone away from home, but he loved my music.” A few years after her husband’s death in 1967 she returned to playing.

The track most closely based on slave narratives is Mama’s Crying Long, written by Giddens, which tells of a woman, who ‘after being repeatedly abused by the overseer, kills him. Nobody knows who the perpetrator is until her son is overheard singing a little song about the blood on her dress’. The horrifying end, which you know is coming, but so want another outcome, is that ‘mama’s in a tree, and she can’t come down’. Sung by all four women, with just sparse percussion and handclaps, it is a searing, powerful song that directly speaks of the reality of life for black women under slavery and the lynchings that followed for those that fought back. The following version of Bob Marley’s Slave Driver is not only a slot-in in terms of subject but also musically sits perfectly amongst the other tracks, sounds like it should always have opened with the sound of a banjo and sung by four exceptional black women.

The banjo is very much at the heart of Songs of Our Native Daughters, reflecting the history of the banjo in American blackface minstrelsy from the latter part of the 19th century onwards, before which ‘the banjo was known as a purely black instrument’. Giddens, Kiah, McCalla and Russell are all banjo players. As Giddens said in an article on the Smithsonian website: “People are going to be like, ‘Are there even that many black female banjo players?’ Yes. There’s more than us”; this feels like a line in the sand. There is more like this to come, with a new album by Giddens and Francesco Turrisi, titled There Is No Other, due out today and then an Amythyst Kiah album, again produced by Dirk Powell, due out later in the year.

The supporting cast cannot go unmentioned, providing unobtrusive, apt backing throughout. Dirk Powell was not only studio host and co-producer but also played the accordion, banjo, bass, guitar, electric guitar, fiddle, keys, mandolin and piano. Giddens says of Powell in her introduction: “after he co-produced my civil rights record Freedom Highway, I knew he would be the perfect partner for this. He leads a session in a way that invites nothing but inspiration and openness”. Jamie Dick and Jason Sypher from Giddens regular band respectively play percussion/drums and bass.

There is an emotional depth to Songs of Our Native Daughters; it is so much more than a collection of consistently great songs, played and sung very well. It is no exaggeration to describe it is as being a cultural landmark. In some respects, it sits somewhere between the music of Carolina Chocolate Drops and that essential need to understand and learn from history, a desire that drove Freedom Highway, Giddens outstanding 2017 album (reviewed here). Moreover, in ‘interpreting, changing, or creating new works from old ones’ this album not only gives voice to the neglected history of black American women but in doing so also asserts a collective, leading role for black women musicians in telling those stories and placing them in context of the world we live in today.

Songs of Our Native Daughters is a cultural landmark both for these extraordinary musicians and hopefully for others inspired by them, as well as those of us fortunate enough to hear their work.

Order Songs of Our Native Daughters via Amazon