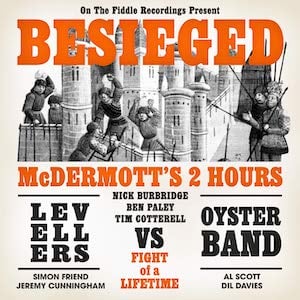

McDermott’s 2 Hours Vs Levellers/Oysterband – Besieged

McDermott’s 2 Hours Vs Levellers/Oysterband – Besieged

On the Fiddle – 22 February 2019

McDermott’s Two Hours release of Besieged marks the end of nearly 30 years of music-making – or as they like to put it ‘not so much a final curtain as a magnificent encore.’ It’s hard to disagree. Both the Besieged set and the bonus Anticlockwise disc showcase the group’s energetic approach to what might best be described as melodic punk-folk.

Heraclitus once asked that if the handle and then the head of an axe were replaced would it be the same axe? A similar question could be asked of McDermott’s Two Hours. Formed in 1986 by Nick Burbridge, Burbridge remains the only surviving member from the original line-up to play on Besieged. Yet the signature sound, lyrical approach and vibe remain intact – helped by the members of The Levellers and The Oysterband who have shown up to help out. All three groups have a shared history, having made three albums together at the start of the millennium.

It’s an approach that serves the songs on offer well. McDermott’s Two Hours have often been compared to The Pogues. The overlaps are obvious: both groups emerged at around the same time and both welded the DIY ethos and energy of the punk era to the instrumentation, arrangements and history of Irish traditional music. But Shane McGowan sounded like he had swallowed the Irish songbook whole in order to explore the no-man’s land between two countries and cultures equally connected and divided. The Pogues were defined by a sense of wild anarchy and overt political positioning, explicitly reflecting the escalation of the Troubles; Ireland and Britain’s troubled relationships and rich histories, and the problems of being Irish at home and abroad. By contrast, Burbridge’s explores these concerns in a more localised and personal series of vignettes – the site foreman who is a ‘bastard’ to work for; the red-haired Irish woman ‘you come to call your wife’; the hard-drinking girl who quits the convent, hits the town, does jobs for the ‘boys’ and ends up with a bottle and memories in a room in Camden Town. These are songs of the diaspora experience – direct, uncompromising, but no less shot through with their own mythologizing of the narratives of innocence and experience. Burbridge’s background as a writer of short stories, plays, poetry and a novel is reflected in lyrics that move beyond traditional rhyme schemes and tropes to explore the corners of their stories and scenarios. Even when what’s being talked about are real events, Burbridge resists a temptation to make the politics and personalities clear-cut and politically polarising.

For example, Erin’s Farewell time signature and melodic, quasi-traditional melody line talks about the difficulties faced by a farming man who leaves Ireland in search of work in London, and finds it in the way that Irish migrants have for centuries: hard, physical work. It undercuts the traditional narrative in these circumstances to explore the tensions of someone tied to their home and their family but who burns with a hunger to leave. By contrast, This Child burns with righteous anger, exploring gun violence in Manchester with a savage lyric that asks the question as to how shooting a child makes someone a man. The track pulses with heavy, dark energy that is underscored and emphasised by a midpoint cello interlude. Some tracks have the lighter, wilder energy of the ceilidh, such as Tha Damned Man’s Polka, while others explore a gentler, tender acoustic side, like All That Fall, which builds to support the chorus line ‘all that fall can rise.’

It is not a criticism to say that the songs are fairly uncomplicated. They’re direct, using arrangements and chord progressions you will have heard before. But the wall of sound attack is refreshingly direct, and it is leavened by the use of traditional instruments to add colour and counterpoint to the hammering bass and drums and squalling guitars. Short fiddle, accordion, flute and whistles all are deployed to provide variation and colour to Burbridge’s impassioned and clear vocals.

Christy Moore once talked about the difficulties of being Irish – hard at home, hard away from home. The tension between either needing or being compelled to leave home and the yearning and nostalgia it engenders in those who have left is common to all diasporas – but it’s always been central to Ireland’s cultural-historical narrative. These themes are ably, enthusiastically and enjoyably explored here. Alternately rabble-rousing, thoughtful, pointed and lyrical if this is to be the end of McDermott’s 2 Hours then both sets see them going out in style.