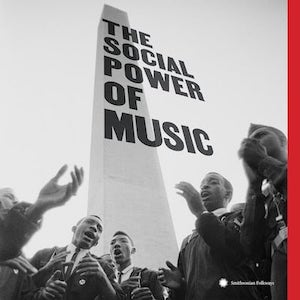

Various Artists – The Social Power of Music

Various Artists – The Social Power of Music

Smithsonian Folkways – 22 February 2019

“Can Music change the world? Some think it can’t; others think it can, or at least serve for a catalyst for change” – Huib Shippers

Smithsonian Folkways Recordings presents The Social Power of Music an exhaustive and eclectic 83-song anthology (with an accompanying 124-page book) centred on the redemptive and revolutionary power of music. Across 4 CDs, which range from parties to protest to prayer, we are invited to share in the joy and strife of some of histories most radical and emblematic social and political figures. That said, the real beauty of this collection is found in hearing these contrasting voices together here in harmony, heard as one irrepressible concordance with enough clout to echo on through the ages.

Smithsonian are famed for their inclusive documenting of music from around the world, striving always to uphold the legacy of Folkways Records founder, Moses Asch. His team knew no bounds in their exploration of new sounds. Whether it was thunderclaps, tree frog choruses or Timothy Leary guiding you through an acid trip, Asch’s ‘encyclopaedia of sound’ was the only entry point. As David Jasen put it in World of Sound: “Moses Asch had a philosophy of music which just took my breath away. Everything to him was folk music. If a person, a folk composed it, it was folk music and that was a wild concept.” The Smithsonian acquired the Asch estate in 1987; so much of this release is made up of Folkway recordings, alongside selections from Arhoolie, Paredon, UNESCO and more.

Spanning cultures and genres it’s all captured here: the pain, the passion, the uprising and the unrest. Like the best withstanding folk music, each performance is a snapshot in history, a time-travelling relic, first to be enjoyed and then to be explored deeper. Many strike hard from the off, whereas others call for further excavation. Whittled down from almost 60,000 tracks, along with capturing the raw energy of live performances we are also invited to consider the songs permutations, their origins and how they are used today. As well as reflect on the turbulent events that framed them. The Navajo Indian Night Chant was a secret and sacred ritual integral to a tribes entire existence for example; it’s interesting as a listener to remember a good deal of these recordings often stretched beyond mere entertainment purposes for the performers involved.

“There is no conservative Folkways record,” claimed critic Dave Marsh “what Asch considered it his job to do was to see where that intersection between politics and music lay,” and this crossroads is where we begin our odyssey. Comprising of topical songs, protest songs and songs of struggle, Disc One chiefly concerns the social movements of the United States in the 20th Century.

Civil Rights anthem We Shall Overcome opens. The resounding ‘We’ sung by The Freedom Singers and their audience, echoes loud and clear right through this song set. As it dies down we’re met by the immutable voice of Dustbowl balladeer Woody Guthrie, as he trips down that freedom highway on This Land Is Your Land, one of the most well-known tunes in the American Folk song canon.

Pete Seeger and Lee Hay’s labour ditty If I Had A Hammer is offset by the chilling conviction of Peggy Seeger’s Reclaim The Night. “Our system gives the prize to all who trample on the weak and small,” sings an indignant Peggy. “The reasons for the marches persist, and so do the demonstrations,” reads the liner notes, which rings particularly true when considering our current #MeToo feminist movement.

“Foster children of the Pepsi generation (…) watching war movies with the next door neighbour, secretly rooting for the other side” testify Chris Kando Iijima, Joanne Nobuko Miyamoto & Charlie Chin on We Are The Children, highlighting the daily hardships of Asian Americans at the time against a San Franciscan soft psych groove. Fannie Lou Hammer leads the congregation on the gloriously righteous I Woke Up This Morning and then Country Joe McDonald’s solemn kazoo pipes up for the Anti-Vietnam song I Feel Like I’m Fixin’ To Die forever immortalised by his iconic 1969 Woodstock performance.

The Western trot of Kristin Lems’ Ballad of the ERA sets a similar tongue-in-cheek tone, “Well I’m only Adam’s rib, keep me safe within my crib.” Recorded live at the final Equal Rights Amendment rally in Lafayette Park, Washington DC, Lems’ mused “I marvel that the singing shows such good cheer and resolve when you consider everyone there was having nervous breakdowns. In a way, the rally was a mass therapy session!” This sense of spirit continues to prevail.

Pete Seeger’s short sweet meditation on death ‘Where Have All The Flowers Gone’ is followed by the Chicano Movement’s Quihubo Raza (What’s Happening, People) with Disc One closing with Barbara Dane and The Chambers Brothers unflinching, masterfully sung rendition of It Isn’t Nice.

Gospel, hymns, spirituals and sacred harp music rooted in the Christian tradition – as well as Islamic, Jewish, Buddhist, Native American prayer – make up the holy throng of Disc Two’s Sacred Sounds. As D.A Sonneborn rightly outlined in his introduction “Sacred music uplifts, immerses, binds, or bonds people together in community. It expresses faith, and with it shared feelings of awe, peacefulness, transcendence, wonder or, joy.”

The rich and resonant vocals of The Old Regular Baptists on Amazing Grace and the acapella walking bass of the Paramount Singers on Peace In The Valley feature alongside the ceremonious hollering and pitched clucks of the Navajo, Plains and Southwestern Indians. The measured fugal phrases of shape-note singers are met by three intriguingly different calls to prayer; the Islamic adhān, three combined examples of Buddhist chanting and the elaborately embellished Jewish Kol Nidre (not technically considered a prayer) that almost feels Qawwali in its microtonal melody. The playful Country swagger of popular religious numbers Will The Circle Be Unbroken and I’ll Fly Away will be recognisable to any Bluegrass fans here.

However, Disc Three is where the serious foot tapping, hip swinging and toasting begins, as it celebrates the regional music and dances of the USA. From Caribbean Carnival Street Festival vibes to Norteno music (Mexican music fused with rock and Polka), with Zyedeco, Western Swing, Mariachi and modern Native Indian music making an appearance too. The atmosphere here is inescapable and intoxicating, all you can do is soak it up. You can picture Cajun showman Austin Pitre whiling-out on his accordion behind his back on Jolie Blonde (Pretty Blonde) or taste the beer suds as The Goose Island Ramblers rattle through the liquored-up In Heaven There Is No Beer, or feel that groove and the sweat pore down as Sam Brothers Five let loose with the Zydeco funk of SAM (Get Down).

There’s the strong singing tradition of The Gullah (African American people residing on the coast of South Carolina) displayed by one Janie Hunter (and enthusiastic support from her entourage of little ones) on children’s ring game Johnny Cuckoo. Which is later followed by the ecstatic, verging on erratic, Oylupnuv Obrutch (The Broken Hoop Song) performed by The Golden Gate Gypsy Orchestra.

But it’s not all play, as we hear next on Rooster Call recorded by John Henry Mealing and co. as they demonstrate how railroad workers would pound out a rhythm and move a 400-pound rail at the same time, whilst slipping in veiled slights about their overseers. With its African roots and improvisational jazz edge, the Liberty Funeral March is another favourite cut, as Brass Band members sing out their parts in a stressed, emotional manner meant to mirror the crying and wailing of grieving family members. As an Unknown orchestra draws the curtain on Disc Three with a bombastic Star Spangled Banner, our focus is then widened to engage social justice now on an international scale with Disc Four’s Global Movements.

Here we face deeply affecting individual accounts that can go beyond peaceful protest in favour of direct action, often referring to or either ending in, a litany of tragedies (e.g. blacklisting, deportation or assassinations). Whether it’s the pained vibrato of a mother’s lament after her child has been deported on Mon’ Etu Ua Kassule, Grupo Raíz’s grand Nueva Cancion about the disappearance of political prisoners or the fierce Anti-apartheid force of South African refugees in Tanganyika on Izakunyatheli Afrika Verwoerd (Africa is Going to Trample on You, Verwoerd) these are some of the most gripping tracks featured across The Social Power of Music.

Pete Seeger’s activist tenacity features again on Viva la Quince Brigada (Long Live the 15th Brigade) a song detailing how members of the XV International Brigade held the line in Madrid during the Spanish Civil War. Elsewhere we hear the proud dramatic poetry of Expresión Joven’s A Desalambrar (Tear Down the Fences) and the failed utopian dreams of Yves Montand on the elegant Le temps des cerises (Cherry Blossom Time). Bringing to mind Viktor Frankl’s noble fight for survival in Nazi internment, we hear Polish-Jewish Holocaust survivor Cantor Abraham Brun’s Yiddish strain on Why Need We Cry? in his resilient response to mass genocide.

“We deem it our duty to record these songs, so that they might not be forgotten,” insists Brun on the Songs From The Ghetto sleeve. It’s a touching tribute and one of many moments listeners might carry with them. As Deborah Wong succinctly writes in the liner notes “Music carries memory into the future, actively producing memory as a tool for change. Performance becomes performative: singing creates a new social reality.”

For me, this anthology magnificently fights and closes the case for Huib’s introductory quote at the start of this review. Not all may agree. However it would be difficult to argue Huib’s next point, “many people believe we live in troubled times. Many of the injustices, much of the bigotry and intolerance in the world seem as disturbing as they were when Asch (first) provided a platform for voices…”

Social commentary and protest has been around long before the early 60s folksinger boom and it will continue as long as people can sing, dance, play and create. It’s still alive in contemporary circles – Hurray For The Riff Raff, Shake The Chains, Will Varley, Stick In The Wheel, Martyn Joseph, Jimmy Aldridge & Sid Goldsmith, Nancy Kerr for example – it lives on in stalwarts such as Young, Baez, Springsteen, Seeger & Bragg and it is not confined to any one genre (see Sleaford Mods, Janelle Monáe, Kendrick Lamar, Ibeyi, Anohi and Pussy Riot for obvious examples). In fact, Dorian Lynskey author of 33 Revolutions Per Minute has talked at length of a current Trump Protest-Song Boom.

With Vice recently claiming memes are now our generations preferred form of protest art whether there’s cause for concern about music’s effectiveness, surrounding the fact the medium and methods are changing, is another matter altogether. As Huib continues “Now, as then, shared acts of music can bring joy, greater connectedness, stronger communities, and a greater sense of fairness; at it’s most powerful, music does seem to be able to help us change the world.” And this is what this astonishingly inspirational compilation celebrates and aims to do in its own way: ‘to surround hate and force it to surrender.’