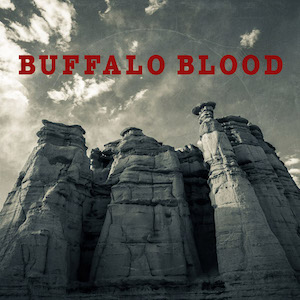

Buffalo Blood – Buffalo Blood

Buffalo Blood – Buffalo Blood

Eel Pie Records – 15 Feb 2019

Renowned for his production work, which, recently, has included Mary Gauthier’s Grammy-nominated Rifles & Rosary Beads, Neilson Hubbard also has a music career on the other side of the glass. Indeed, of late, he seems to have been spending quite a lot of time behind the microphone. Last year saw the release of a new solo album, Cumberland Island and there’s the third Orphan Brigade outing scheduled for later this year. Before that, however, comes this project from Neighborhoods Apart Productions, a film and music company he runs alongside fellow Orphan, Joshua Britt. They’re joined by Audrey Spillman, another Brigade member, and Scottish singer-songwriter Dean Owens who sparked the project when he told Hubbard about songs he’d written after visiting sacred Native American lands. Dean’s own interest began with the Dee Brown’s book Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee (and a lot more research after), and recognition of the parallels with the Scottish Clearances diaspora – some of whom then went on to be part of the problem in the USA.

This led to the four, along with photographer and sound engineer Jim DeMain, travelling 1300 miles along the Trail of Tears, the route on which Native Americans were forced to travel to reservations, to spend two weeks living in the New Mexico desert, the resulting recordings inspired by the visual and sonic landscape and its history, drawing on Scottish and Southern folk roots influences to address themes of displacement, immigration, refugee and the human spirit.

Given that, as far as I can discern, none of those involved has Native-American heritage*, it could potentially be open to white liberal guilt accusations, but that would be to ignore the passion, concern and commitment that drive the material, not to mention the fact that such attitudes dispense with any concept of empathy or shame over your country’s actions.

It opens with an Owens/Britt number, Ten Killer Ferry Lake, the title referring to the eastern Oklahoma reservoir constructed between 1947 and 1952 on land acquired from the Tenkiller Cherokee family. The area has strong links to Native American history and, before 1800, was the ancestral home and territorial hunting grounds of the Caddo and Osage Indians, the latter selling it to an Indian trader named Lovely who established the courthouse that’ served as the seat of governmental affairs. In 1829, the area was decreed “Cherokee Land”, and the white settlers forced to leave, the Eastern Cherokee Nation relocating here when they were driven from their homeland down the Trail of Tears in 1838-1839, up to 8,000 dying along the way.

As such, built around hollow funeral march drums, percussive clicks, ambient background noise, Owens’ ghostly whistling and echoey vocals, he sings how “spirits of the past walk beside me” and of the lake washing souls. Owens take the credits for the next two tracks, I’m Alive a slightly more uptempo slow march, mandolin-backed that, again featuring whistling, speaks of the ties to the land where the buffalo bones lie and echoes the theme in lines like “spirits of the past walk beside me” and how “among the dust and the dreamcatchers/Among the desert trees/Where Mother Earth and the moon guide me/ I’m never lost.” Set to a strummed beat, Reservations is a more direct number about the displacement of the Native Americans and the destruction of their way of life by the white man and their broken promises, always taking what they want.

Another Britt-Owens co-write, musically calling to mind America or CS&N, the languidly-paced Beneath The Golden Sky paints an evocative picture of the desert before leading into three Hubbard numbers, first up being the mandolin-flecked, dust-dry, almost lullaby-shaped strum of Daughter of the Sun where, in parched tones, he sings how a “Mean old snake with a red fork tongue took my baby away” and the resigned call to “Lay down your bows lay down your guns/These wars won’t stop the pain.”

Sung by Owens, the title track follows, tribal chant introducing a focused narrowed-eyed rhythm driven by acoustic guitar and coloured by piano and tambourine, gradually picking up tempo and evoking Neil Young with the lyrics offering up the defiant “I still run like the blood of the buffalo/From the veins of my father’s fathers” despite the “fallen red trees/Where the trail leads/Into disease.” The third, White River, is a co-write with Spillman, who also sings vocals, a sparse and moody acoustic evocation of the journey along the Trail of Tears, the title referring to the Mississippi tributary that formed part of the route, and “the sound of the children coming home.”

Musical muscle is flexed for Comanche Moon as Owens relates the tribe’s destruction at the hands of the white settlers, setting their stories of ‘honour and glory’ in the context of the devastation wreaked on those they saw as just savages, promising freedom in the name of God, but instead taking away liberty and dividing the Comanche nation, homing then on a reservation with “no trees, no elk, no buffalo/Just sickness and starvation.”

But while the project highlights the injustices inflicted on the Comanches, it also celebrates their pride and refusal to be broken, notably so on Carry The Feather, a simple strum matched by an equally simple chant-like lyric in which the protagonist sings “I still carry the feather”, handed down by their father.

Again written by Owens, Ghosts of Wild Horses breaks up the narrative with a desert night instrumental whistled against a spooked acoustic guitar that can’t help but summon images of Leone’s Westerns.

Britt’s sole solo contribution, War Among The Nations is another Young-like number that speaks of the dangers of the conflict “ripping out our own hearts” and the “great storm coming” tearing things apart (a number that has striking contemporary resonance with today’s divided America), leading into the aftermath laid out in Bones which, to percussive snaps asks “How can we live in peace/After war destroyed us” and of old friends and long forgotten warriors now “just bones washed by the wind and sun”, as it talks of loss, both of a land and an identity.

It returns to history with another slow, hollow drum beat, Hubbard on keys, for the lament-like Land of Broken Promises with its mention of Crazy Horse’s victory over Custer at the Little Bighorn set against references to the massacres at Sand Creek, in 1864 when the US Army slaughtered or mutilated as many as 500 Cheyenne and Arapaho, mostly women and children, and Wounded Knee in 1890 which left up to 300 Lakota dead.

It ends with a brace of Hubbard/Owens co-writes, Buffalo Thunder, a mournful tribal chant couched in sampled desert sound recordings, preceding Vanishing World, both an epitaph to a “soon to be forgotten” culture, “wrapped in the clutches of a dead man’s hand”, but also a call to still hold that great spirit in the hearts of those who carry the mantle of the past and to remember with pride and dignity from where they came even as they are left “howling like the wolves into the winter wind.”

The album is as potent as anything written by Buffy Sainte-Marie and deserves to be acclaimed up there alongside Tori Amos’s Scarlet’s Walk album, Dave Matthews’s Don’t Drink The Water, Elton John’s Indian Sunset and Robert Plant’s New World, just a few of the mere handful of songs by non-Native Americans that have sought to expose the injustices inflicted on the First Nation.

More here http://www.buffaloblood.com/

*Addendum: it transpires that Stillman is, in fact, part Cherokee on her paternal grandfather’s side, but this has consciously not been promoted.

Photo Credit: Jim DeMain