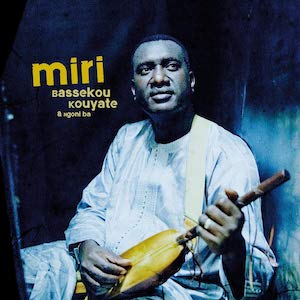

Bassekou Kouyaté & Ngoni ba – Miri

Bassekou Kouyaté & Ngoni ba – Miri

Outhere Records – 25 January 2019

There can’t be too many musical forms that have a history of over 2000 years, even less a musician who can claim, as Kouyaté does, the ability to trace family roots, through generations of griots, back to ancestors who played for kings and queens before the time of Christ.

Born in Garana, a small village on the banks of the Niger River in Mali, Bassekou Kouyaté‘s early career saw him playing with kora player Toumani Diabaté, with whom he became a founding member of the former’s Symmetric Orchestra. In the mid 1990s, he married Amy Sacko, herself an acknowledged griot singer, and the pair began establishing a growing musical reputation within Mali. 2005 saw him invited, by Mali’s ‘desert bluesman’ Ali Farka Touré to play on both his Savane album and final tour. In the same year, Bassekou also decided to form his band Ngoni ba.

Since the 13th century, the ngoni has been the principal instrument in the griot storytelling tradition. Lute-like in appearance, Kouyate has been known to describe it as the ‘guitar’s grandfather and banjo’s father’. Traditionally, the role of the instrument in West African music had been akin to that of the rhythm guitar, with the kora being used as lead. Bassekou Kouyaté‘s maverick approach, however, tore up this blueprint.

Adding extra strings to the traditional ngoni, together with inventing customised medium and bass versions of the instrument, thus increasing harmonic flexibility, alongside introducing electric effects, within Ngoni ba it became the lead, relegating the kora. Further flouting long-held conventions, by standing to play, Western rock -guitar like, initially using a bicycle inner tube as the strap, his innovations effectively re-wrote the rulebook, perhaps much in the same way as did Fairport Convention, (and others), with the electrification of folk in the UK.

Miri is Bassekou Kouyaté‘s fifth release, and sees him in a more lugubrious, reflective mood, ‘an album about love, friendship, family and true values in a time of crisis.’ Whereas 2013’s Jamo Ko saw distortion and wah-wah pedal effects, and previous release, 2015’s Ba Power presented an even more rock-oriented and electric approach, this latest offering sees a return to the more traditional sounds of his village roots which pervaded his debut, award-winning record, 2007’s Segu Blue.

Recorded in Kouyaté‘s own Bamako MBK studio, the album benefits from the support of not only esteemed Malian musicians but also several international guests. At its core, however, Miri¸ indeed Ngoni ba the group, is very much a family affair, with close and extended family members contributing. Sleeve note credits highlight Bassekou Kouyate (lead ngoni), Abou Sissoko (medium ngoni), Madou Kouyate (bass ngoni), Mahamadou Tounkara percussion (doundoun, yabara, tama) and Moctar Kouyate (calabash) along with Amy Sacko, Kouyaté‘s wife, providing lead and backing vocals.

The disc opens with a perfect declaration of the album’s intent, as Kanougno, a song of a lover searching the town searching for his loved one, has Amy‘s husky vocals weaving not only around the hypnotic, rhythmic instrumentation but also the oud and vocals of featured Moroccan guest Majid Bekkas. This really sets the scene for the further joyous, uplifting sounds that follow.

Deli, a song calling on people to appreciate the beauty and value of friendship, rather than putting money before ‘amité’, sees Amy‘s lead vocals augmented by quite stunning harmonies from special guest Kankou Kouyaté, daughter of Fousseyni, Bassekou‘s brother and former band member, who provides backing vocals throughout. Habib Koite, an old friend from the Symmetric Orchestra era, is the featured vocalist on Kanto kelena, (‘She left me alone’, in translation), a song imbued with the sounds associated with Tuareg desert blues

Don’t leave me alone, I am drowning in sadness.

You bring me shadow from the sun, don’t leave me.

Have mercy

That the album features a nostalgic song about Mali’s predilection for Cuban music, Wele Cuba, should come as no surprise given its popularity post-independence in the 1960s when Bassekou grew up listening to bands such as Maravillas du Mali. The song, emanating from a spontaneous jam session in Bassekou’s studio in Bankoni, highlights Amy Sacko and Kankou Kouyate being answered by Guantanamo singer Yasel Gonzalez Rivera in what might be construed as a Malian-bomba hybrid.

There is little doubt that Mali’s recent history and current predicament is a troubled one, and the instrumental song which gives the album its title, Miri, not a reference to the coastal city in Sarawak, rather it means ‘dream’ or ‘contemplation’, references the ruminations undertaken by Bassekou when he tries to escape the noise, stress and political turmoil on the banks of the Niger near Garana. The virtuosity of his playing here is mesmerising, underlying the fact that the ngoni is capable of delivering expression.

Kouyaté is not afraid to address political concerns. Wele ni is a song in which the literal meaning concerns a king from Segou who does not treat his people with respect, metaphorically, however, it is a comment on the 2018 elections in Mali, and the high levels of self-interest of many politicians. Another guest, legendary singer Abdoulaye Diabate takes the lead vocals here, with Bassekou, ever the innovator, playing slide ngoni with a bottleneck for the first time. In a similar vein, Konya, (translated from the Bamara as ‘jealousy’), addresses what he sees as an evil capable of not only tearing families apart but also the destruction of Africa. Musically, this is reflected in a strident lead ngoni, matching perfectly Amy’s stentorious vocals in a track which also features guitar from Snarky Puppy‘s Michael League.

In contrast, Nyame, with its haunting, rhythm and beats has lyrics which are delivered in a sonorous, at times spoken, manner, and careful listening also reveals bluegrass fiddle from Casey Driessen. In addition to a second appearance from Abdoulaye Diabate, another American guest, Dom Flemons, features on the next track, Fanga, although not as might be expected on banjo, rather he plays bones, on an up-tempo, toe-tapping song concerning force and power. With the penultimate cut on the album, Tabital Pulaaku, Bassekou revisits a sociopolitical theme, as Afel Bocoum sings of tensions and conflict between nomadic herders and sedentary farmers, an issue which is being exacerbated by the effects of climate change.

The album ends with Yakare, a homage to Kouyaté‘s late mother who supported her family by travelling around West Africa singing, with the then teen-aged Bassekou playing his ngoni. Out of respect, Amy‘s vocals are delivered in the style of mother-in-law.

This is an album imbued with extraordinary and at times beautiful music. The intricate sound of Kouyaté‘s cascading runs and virtuoso picking, augmented by the plucked or strummed medium and bass ngonis, underpinned with exhilarating percussion makes for an enervating listen.

In Bambara, the national language of Mali, whilst ‘ba’ can translate as ‘group’ it also means strong or great. Miri is certainly one very ba release.