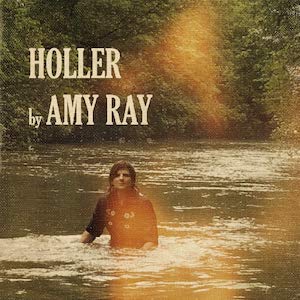

Daemon Records – 2 November 2018

Following on from the recent live Indigo Girls double album with the University of Colorado Symphony Orchestra, Amy Ray returns with her sixth solo studio album. While not a concept per se, Holler is conceptual in as much as it draws on her Southern upbringing, Georgia home and religious beliefs for songs about immigration, racism and trying to balance her life as a “left-wing Southerner who loves Jesus, her homeland and its peoples”.

Variously inspired by Jim Ford’s 1969 album, Harlan County, Jennifer Lawrence film Winter’s Bone, 40s’ Appalachian poet Byron Herbert Reece and black American author and civil-rights activist, Toni Cade Bambara, Holler embraces a wide Americana spectrum, from Southern rock and bluegrass to gospel and traditional country, with musicians that include Jeff Fielder, Derek Trucks, Adrian Carter and banjo star Alison Brown.

The lazily drifting 42-second instrumental Gracie’s Dawn (Prelude) with its pedal steel brass, strings and piano eases you in, flowing straight into Sure Feels Good Anyway, an out on the road heading back home driving rock number that lays out her ambivalence about her Southern identity (“I know that you don’t like me/But it sure feels good anyway”) and living “in the backwards South” as she asks “ain’t ya tired of fightin’ ‘bout that damned ol’ flag?/Well it ain’t Southern pride, it’s just Southern hate.”

Featuring Brown’s banjo, Fielder on baritone guitar and harmonies from Lucy Wainwright Roche, Dadgum Down (a Southern variation on goddamned) rides an almost tribal rhythm for a lyric about coming off drugs and the end of Spring leaving the singer in a funk.

The first number to nod to her Christian faith, with Brandi Carlile and Vince Gill on harmonies and featuring brass, strings, banjola and 12 string guitar, Last Taxi Fare is a slow waltzer allegory with the cabbie as the Good Samaritan picking up the downhearted drunk at the bar to see him safely home, God sending an angel “to teach you to fly/Above all your transgressions, the fears of your life.”

Another short bridge reverie, with Fielder on dobro and arranged for strings, Old Lady Interlude’s melody and Ray’s singing conjures a folk hymnal before things kick back into bluegrass-laced Southern boogie gear with Sparrow’s Song. The title’s a reference to both Reece and his poem Whose Eye Is On The Sparrow, itself a reference to the gospel hymn His Eye Is On The Sparrow which, in turn, draws on verses from Matthew’s Gospel about God keeping watch over his flock, although the line “Every seed that you sowed, every word that you wrote/Brought another sparrow home” is rather at odds with the poem in which the bird dies because God took his eye off the game.

Following the decidedly bluegrass coloured Oh City Man (a number that starts recalling how America’s cities are built on sacred Indian land and ends with an image of homelessness), Fine With The Dark strips it right back to just Ray and acoustic guitar, channelling Freight Train writer Elizabeth Cotten’ s fingerpicking style on a song inspired by both a New York blackout that allowed the stars in the sky to be fully seen and how the night would be a time of relief for those who worked in fields all day under a burning sun.

By way of a thematic digression, the waltzing Tonight I’m Paying The Rent heads into the honky-tonk with the Wood Brothers on harmony for a song that’ll strike a chord with every grafting musician, followed in turn by the soulful country of sparsely-arranged title track’s plaintive wish for reconciliation after a fall-out as she sings “I don’t take much stock in heaven/If I can’t make this right with you.”

Things get shook up again musically with dobro, banjo, fiddle and mandolin bearing aloft the mountain gospel bounce of Jesus Was a Walking Man, which, featuring a spoken passage by Rutha Mae Harris from the Freedom Singers, offers a refugee-themed lyric that references Somalia, Syria, the Sudan and Afghanistan as well as Mexico and Honduras preaching the message that, while some would build a wall, “Jesus would’ve let ‘em in.”

Sparrow’s Lullaby offers a brief reprise of lines from the earlier number, but here in the same musical setting as Old Lady Interlude before Trucks joins the line-up on slide guitar for Bondsman (Evening In Missouri) which, about the hardships of life in the Ozarks, was originally intended for the last Indigo Girls album in 2015 but never made the grade. Having worked on it since, it finally surfaces, recorded live with brass and strings, a soaringly sung spiritual about the burdens of legacy (“I am my father’s daughter/I got his crimes just hanging on me”) and a call for relief from suffering (“Oh Lord, let me sleep through the thunder/Let me sleep through the rain/One more night before the bondsman comes/And takes it away”).

The final listed track, dedicated to Bambara and featuring Justin Vernon on harmonies, set to a slow-march tempo, Didn’t Know A Damned Thing, returns to the theme of Southern racism with a powerful indictment of growing up in ignorance in Georgia, “singing my heart out for the land of the free” round the Girl Scouts campfire under the shadow of Mount Rushmore, while the school books and church groups never spoke of the hangings and the burnings in Atlanta and Alabama, as, building to a horns, electric guitar and pedal steel climax, it ends “I was reading my history, but it didn’t say a thing about the kid sitting next to me.”

There is, however, one final, hidden acoustic number, guessingly titled On Down The Line, that, expanded to four minutes, echoes the wistful words, sentiments and American Trilogy (Newbury not Presley) sound of Old Lady, a terrific low key but resonant end to a love letter to her home, written with affection, but the ink sometimes run with tears.