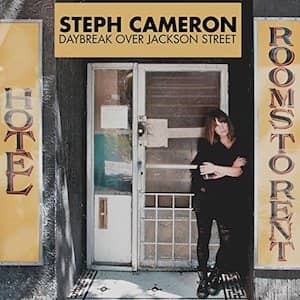

Steph Cameron: Daybreak Over Jackson Street

Steph Cameron: Daybreak Over Jackson Street

At the Helm Records – 10 November 2017

It’s not unusual for artists plying an Americana trade to be likened to such names as Townes Van Zandt, John Prine and Bob Dylan, but the artists in question are usually men. It’s rare for a female singer to attract such comparisons. Vancouver’s Steph Cameron is both an exception and exceptional.

Armed with just an acoustic guitar and occasional harmonica, Daybreak Over Jackson Street is her second album and the first to make it past the Canadian borders. Her debut, the Dylan-referencing Sad-Eyed Lonesome Lady, laid out her stock in trade with a set of songs clearly influenced by the 60s folk movement of Greenwich Village and this follows the same course, albeit with a more considered approach with its sparsely produced, more intimate sound and reflective songs of love, loss and finding hope in dark times, some very personal, others more observational storytelling.

Much draws on her formative years on Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside, most specifically the fingerpicked opening number, Daybreak Over Jackson Street, a vignette of morning dawning on one of the city’s less salubrious quarters where “There’s people behind boarded doors, there’s beds and blankets on the floors…gardens gated and fences grown” and the local gangsters hang out “dressed the part from head to toe.” Given the reference to “the way their badges glow” and how the law “issues justice from a whip, sends bullets fired from a clip”, the suggestion is that these are may well be the cops, as corrupt as the politicians who keep the people down. Her voice here, soft, breathy and slightly husky, reminds me of the young Melanie without the dramatics.

The wearily reflective Young And Living Free calls Wednesday Morning 4 am era Paul Simon to mind as she looks back on dreams washed away or overgrown when “the world was wild and it was only here for me.” This, in turn, gives way to That’s What Love Is with its circling guitar pattern, a sketch of love lost in symbolic terms as, for example, “a child’s balloon on it’s way past the moon”, sitting alone in the kitchen, “an echo from the trailer door” or the time “late at night when the coyotes call, the dogs whimper and the leaves fall.” By contrast, love in tune is the subject of the jaunty strum of Sing For Me with its catchy refrain “Oh come on baby, let’s sing for free, I’ll sing for you and you’ll sing for me.”

If there’s a hint of Woody Guthrie here, his spirit is fully evident on the playfully upbeat Little Blue Bird, a restless hobo-themed song about empathising and sharing kindness. By contrast, the moody, traditional-like Peace Is Hard to Find put me in mind of the darker shades of Pete Seeger while she also digs into old school folk blues for the cocaine habit of On My Mind with its wailing harmonica.

You Oughta Know By Now, where she shows a worthless lover the door (“you ought to know by now there’s nothing here worth fighting for. I’ve known your kind of loving, I’ve walked this road before”) represents the most obvious Dylan influence while, harmonising with herself and again evoking Melanie, California has a poppy sheen reminiscent of Glen Campbell.

The whole album is superb, but two numbers, in particular, stand out. The lovely, melancholic Winterwood, a winter-set song about returning home with its image of a deer on the highway “her eyes a-shining like some silver on the moon” is haunted by the ghost of Townes. The other, Richard, is my personal favourite, pure Prine in its bittersweet memories of a troubled old friend who, guessingly suffering from depression, “never made it out of east Vancouver”, the line “a hotel is a real sad place for livin” linked by a reference to The New Sun Ah, a retirement home hotel for senior citizens on East Pender St in Chinatown. It ends with the crushing line “But years just sort of go and I could never stay. Richard, I never thought it would end this way.” For Cameron, however, this is just the start of what promises to be a brilliant career.

Photo Credit: Mark Maryanovich