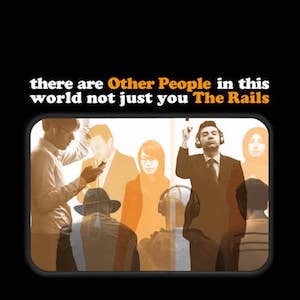

The Rails: Other People

The Rails: Other People

Psychonaut Sounds – 1 September 2017

As most of you will be aware, The Rails is nominally a duo comprising Kami Thompson (daughter of Richard & Linda) and James Walbourne (Kami’s husband and The Pretenders’ lead guitarist). After getting together in 2011, it took them nearly three years to come up with their debut album, Fair Warning (reviewed here). This created quite a stir on its appearance in 2014, gaining great reviews and accolades and scooping prestigious awards (among them Mojo’s Folk Album of the Year and the prize for Best Newcomer at the BBC Radio 2 Folk Awards). Fair Warning was a deliberate attempt to create “a ’70s-sounding folk-rock record”, and scored extremely highly on that and all other counts. With its authentic sensibility, superb songwriting, assured singing and playing, and confident arrangements – somewhat vintage Richard & Linda in many ways, I thought at the time, albeit more in terms of sound-world than any deep doom’n’gloom of the lyric content. But there was also an indefinable extra pizzazz which, though clearly informed by approved folk-rock templates, was infused with a gutsy contemporariness (even on the album’s two covers of traditional songs).

The three-years-on followup record, Other People, has been dubbed by its creators “folk-rock on steroids”. In terms of both writing and execution, its ten original songs (no trad-arrs this time around) exude an even more finely honed classiness than those on Fair Warning but without shortchanging on the gutsiness, and lyric-wise are found majoring even more on quintessential 21st century concerns while attempting to come to terms with the changes happening around us. ‘Twas ever thus, for sure, so here Kami and James are “railing” (of course!), angrily, at the desecration of the “real” London (Brick And Mortar and The Cally) while becoming increasingly exasperated at the uncaring, unseeing attitudes of Other People. Alongside these concerns we encounter powerful songs dealing with the contradictions of the current age of austerity (Leaving The Land and Mansion Of Happiness) and the downsides of relationships – the perennial tussles and inherent fragility (Drowned In Blue) and the issue of domestic abuse (Dark Times, a confession of brooding regret rather than savage indictment). In the latter respects especially, it’s hard to avoid hearing clear parallels with the obvious songwriter role-model of Kami’s dad, but there’s more in the way of compassion and less in the way of viciousness to be found in the couple’s writing.

Moreover, their own vision of our age is probably more unilaterally universal since the angle and level of personal angst is more detached. Perhaps the most personal (in terms of direct experience) of The Rails’ new songs is The Cally, a reflection on the transformation of one of London’s major arterial thoroughfares, the Caledonian Road, from the age conjured by the recollections of James’ grandfather Sidney. This song and Leaving The Land are probably the closest the album gets to folk, built on a solid acoustic base and imbued with a slightly Celtic aura. Elsewhere, the Rails’ musical styling is a cross between Brit-folk and Americana but with more of a punch and a leaning towards a kind of retro-’60s psych that’s likely more Kennedys than Thompsons.

The brilliantly alert production is by Ray Kennedy (no relation to the above-mentioned Pete and Maura as far as I know), whose stated brief was to retain “a sense of power, presence and intimacy”. This was achieved, not least by a recording schedule that nailed the music down in just seven days, with an on-the-edge punchiness and an immediacy that belies the obvious carefulness of the arrangements. There’s an air of relaxed accomplishment and keen musicianship from the core band (Kami, James, drummer Cody Dickinson – who’d appeared on Fair Warning too – and bassist Jim Boquist). James Walbourne in particular impresses – he turns in some killer guitar solos that leap out at just the right moment to tingle the spine and then beat a swift retreat to regain the focus on the song. James is not only a really inspirational guitarist but also a versatile multi-instrumentalist with an ear for appropriate keyboard colourings that give the music a keen and distinctive temporal identity. Indeed, there’s an abundance of imaginative instrumental touches throughout the album – for instance, the heady twang of Late Surrender leads us through gothic-noir Americana verses into a Richard-&-Linda-style chorus, which is all then capped by a climactic guitar solo that arises almost incidentally to serve as the song’s coda.

OK, I don’t like to keep on referencing Richard Thompson (it might seem that I’m just peddling a tired cliché here), but I really can’t help being reminded (albeit sometimes even subliminally I admit) of His Master’s Voice, in resonances and in things like phrasing and chord progressions. For instance, the melodic line of Hanging On could well be vintage Richard-&-Linda, and Kami’s vocal expressiveness often embodies the world-weary plaintiveness of Linda Thompson (it must be in the genes!). Ditto the brilliant craftsmanship of the couple’s songwriting – they sure have a knack for penning catchy hooks which manage to escape glib superficiality in contributing meaningfully and without compromise to the contours of the lyric and the message or argument.

The whole enterprise (like its predecessor) has a supremely classy feel, and the music is pure gold. And – for here’s the rub – it’s deserving of a better presentation than the accompanying skimpy packaging which is pitifully uninformative and without lyrics, such a needlessly minimalist approach to presentation really does no favours for the truly excellent music within.

Watch them performing an acoustic version of Hanging On from the album: