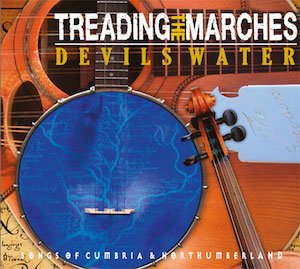

Devils Water: Treading the Marches

Devils Water: Treading the Marches

Osmosys – 2017

The Devils Water brand-name has been around since circa 2010, originally instigated by singer-musician Richard Ridley partly as a vehicle for his own songwriting which, like the rest of the group’s repertoire, sits firmly within the north-eastern traditions (historical, industrial and maritime). Band membership has fluctuated since, with original members Frank Lee and Corrie Shrijver departing after the band’s 2013 debut album and Brian Bell and Robin Jowett leaving after its 2014 successor, and only Richard and his almost-as-long-serving colleague Raymond Greenoaken surviving on into album number three (Treading The Marches), forming what might now be termed the core Devils Water lineup which provides the band’s strong indigenous musical identity.

The new album signals something of a sea change too though, in that it’s produced by stalwart Steeleye Span‘s man Rick Kemp, who also brings along his trusty bass and well utilises the considerable added folk-rock credentials of compadres Ken Nicol on electric guitars and George Omar Hutton on drumkit. The Devils Water lineup on this occasion is completed by Patrick Walker (fiddle, viola, mandolin), and Kate Green adds her superb vocal skills to just over half of the album’s tracks. Although the Devils Water imprint in itself provides a certain artistic, thematic and musical consistency, on Treading The Marches there’s more of an emphasis on settings of texts from traditional and historical sources, and perhaps as a by-product of this we glean more of a marked difference in character between individual tracks. This, however, seems less attributable to any specific diversity of material, more down to the choice of vocal lead; the album marks Raymond’s emergence from the shadows in that respect (though his considerable prowess as an instrumentalist has never been undersold).

Indeed, Richard and Raymond are each allocated an equal proportion of the album’s songs. Raymond’s lighter, thinner-textured tenor, provides quite a contrast to Richard’s stocky, full-bodied baritone; there’s a thoroughly appealing, playful demeanour to Raymond’s invitingly idiosyncratic delivery, and he displays just as much relish negotiating the wordier tongue-twisterie of the jig-like Buck O’ Kingwater as on the stirring reiver-balladry of The Fray Of Hautwessel and the delicious curio A Lyke Wake Song (which turns out to be a Swinburne pastiche of a Scots border ballad). Raymond’s penchant for quirkiness is also displayed in the lively and slightly adventuresome acoustic-based-with-folk-rock-trimmings nature of the arrangements, while he also has puckish fun with an item from the Cumbrian Songs And Ballads collection, Madam Jane, done to the Buy Broom Besoms tune and sporting a chirpy chorus and jolly fiddling that ushers in a chunky, jaunty folk-rock rendition of a tune from the Northumbrian Pipers’ Tunebook.

Richard’s vocal style, on the other hand, is both more straightforward in nature and more in keeping with the “trad-arr/LJE” school of folk-rockery, which you can hear best on the opening track, a satisfyingly heavy-duty electric take on the ballad Hughie Graeme, his sturdy adaptation of Cumbrian versifier Hugh Falconer’s poem The Derwentwater Lights (which retells an eerie local legend) and the catchily melodious “would-be-band-theme-tune” (Devils Water). High Germany, on the other hand, receives an almost too strait-laced generic-folk-rock run-through, which fades just as it should be cranking up the gears into a workout. An almost melancholy air pervades Richard’s singing on the closing track, an imaginatively expanded (by Richard himself) version of Rap ’er T’ Bank, which though providing a continuity of the north-eastern industrial heritage theme from earlier Devils Water offerings, eschews the customary lustier treatment of that song in favour of an altogether gentler, almost mournful reading. Winding down from the rhythm-driven folk-rock of earlier tracks, this is sparsely-scored, with Raymond providing a guitar accompaniment of delicate simplicity to Richard’s tender, reflective vocal (which nevertheless lacks nothing in passion), punctuated by Patrick’s heartfelt, elegiac viola solo. Earlier, when the voices of Raymond, Richard, Patrick, Kate and Rick all sound together, on the largely a-cappella account of The Brampton Girl’s Fear, the combined effect is very persuasive.

Rick Kemp’s able production cannily both makes good capital of varied instrumentation and keeps interesting colours (banjo, Appalachian dulcimer, cittern and Indian harmonium, for instance) in believable perspective without loss of overall drive or weight in the full texture. I could quibble with just a couple of technical issues: the intrusive saturation of background wind-FX on Piper At Capheaton to my mind spoils, rather than enhances, the spooky atmosphere of the tale, and Richard’s vocal is arguably given too much reverb on a couple of other items. In every other respect though, from its stylish performances and sparky arrangements to the commendably well-annotated, attractively-designed booklet and artwork, this is an exceedingly recommendable disc for lovers of songs of Cumbria and Northumberland who like their material rendered with flair and imagination.