When I meet up with Mick Flannery, he admittedly catches me by surprise.

Of course, I know in advance of meeting him that he’s a critically acclaimed artist, no more so than in his home country of Ireland where he has a huge and enthusiastic fan-base. Based on reputation I’m also expecting Flannery to be quietly spoken, self-deprecating and deeply introspective. As we sit and chat, I find him (to a degree) to be all of these things, but what catches me by surprise is that he’s also funny.

In fact, he’s very funny.

It’s a dry sense of humour that Flannery carries into his live shows with great effect, using humorous anecdotes between songs to relieve the tension that inevitably builds throughout the audience when they engage with his, often quite dark, music. His songs are deep, direct and spellbinding in their simplicity. Like a quietly spoken person to whom you lean in to hear them better, throughout his performance Flannery forces you to ‘lean in’ to the stories he tells through his music. At times the effect is mesmerising.

Unsurprisingly this engaging quality is picked up on by critics and music fans alike. Flannery has now four albums to his name, the first released in 2007 when he was just twenty-one and which generated sufficient interest in his work, particularly in Ireland, to position him as a musician of great potential. A year later he released ‘White Lies’ which went platinum in Ireland reaching number 6 in the Irish album charts and in 2012 his third release ‘Red to Blue’ reached number 1 in Ireland and led to a sold-out tour and extensive radio airplay. However, it was 2014’s ‘By the Rule’ that provided Flannery with the greatest personal satisfaction, producing a record that (unlike his previous releases) he can imagine himself listening to for many years to come.

We meet up in Birmingham at the end of his UK tour which has included a number of sold out gigs. Mick is visibly tired from his week’s performances but nonetheless gives me his full and undivided attention, carefully contemplating my questions and providing considered responses that seem even further embellished by his strong Cork accent. He’s as mesmerising in conversation as he is on stage…

We talk about the tour and I wonder how he chooses his live set-list from what is becoming a sizeable back-catalogue; “I tend to play the majority of whatever songs that I have that have medium to upper tempos” he explains, “because I have a lot of really downbeat shit! People can only handle so much of that you know?! I feel you have to cherry-pick the misery. Or the self-involved romantic songs, I don’t want to be too heavy with that.”

“If you do a show with eight or nine really downbeat songs in a row, it can feel a bit indulgent” he continues. “I don’t like that. It implies a self-importance. I can’t get away with that. I have three younger brothers who’d kick the shit out of me if they felt I was some type of shoe-gazing, self-involved songwriter, obsessed with his own feelings…”

Flannery grew up in Blarney, County Cork. He doesn’t attribute much significance to the place of his upbringing in regards to it’s influence on his music, other than than perhaps the space it allowed him to develop. “I grew up on farmland outside a village” he reflects, “and I became self-sufficient. I got Ok with just hanging out by myself. Maybe that had an effect, because I had to entertain myself. I suppose if I’d been born in a city that might be different…”.

I ask whether Mick was the artistic member of his family? “Lads (brothers) can all sing” he replies, “My sister’s older than me, she’s more mathematically minded. She can’t sing even though she’d love to be able to sing. My father hasn’t got a note in his head. So I suppose you could say that I’m the artistic one, but even the word ‘artist’ makes me shudder.”

It’s clear that Mick’s mother had the greater influence on his musical upbringing, introducing Mick to his future craft through family get-togethers and sing-songs. “They’d pass the guitar round” he recalls. “They informed my musical taste. They were all into Tom Waits…Tom Waits was their biggest thing…and all those old romantic songs, what I consider classically good songs; Joni Mitchell, Tracey Chapman, Jim Croce, Johnny Cash.”

“Then I got into Bob Dylan. I got into him after meeting a guy called Ricky Lynch in Cork City. Ricky sang a lot like Bob Dylan and he got me into the albums. He directed me a little bit as well. I bought an Eagles album and he picked it up and threw it away…he didn’t even let me listen to it! He let me keep my Bob Dylan and Nirvana albums but the Eagles were not allowed.”

Hearing about Mick’s earliest influences and reflecting on the simple, stripped-back approach he takes to his song-writing and arrangements, I wonder how much of his style is the result of the artists who influenced him or simply the outcome of his approach to creating and recording music;

“It’s both I suppose” he concludes after a thoughtful pause, “I think it’s a product of the fact that the lyrics are the most important element to me. They get first preference. Anything that’s getting in the way of the story of the song gets chopped. I like simple things, like Johnny Cash’s productions with Rick Rubin. Then when the time is available or right, those type of productions can be quite dynamic and effective because when the song does escape…when I shut up and the band can have room to breathe…then it has an effect I think. Too much noise, it tires you out.”

The importance Mick places on the lyrical aspects of his work is something I’m keen to explore further;

“I suppose you write about what you’re trying to figure out”, he explains, when I ask where the inspiration behind his lyrics comes from. “When you’re younger you’re trying to figure out relationships and stuff like that. If you suffer a breakup, you’ll write about that when it’s all new and you’re naïve to it and the feelings are raw. In the latter albums there’s less of that stuff because I’m not naïve to that any more. Now it’s more about life in general.”

“I’m getting more social in the subject matter” he continues, “which can be dangerous. It becomes political in a way. Your opinion on the world is just your opinion, but singing it and putting it on a CD gives the impression of authority…which is a juxtaposition because it’s still just your fucking dumb-ass opinion. That’s kind of frightening in a way for someone like me. Then again you just have to forget about it. It’s no big deal at the end of the day if someone doesn’t think you’re right.”

As we discuss this point in particular, I sense some unease in Mick. It becomes apparent that this is something that’s been weighing on his mind;

“I have a new song; it describes social unrest” he explains, “It describes a riot and a poor man breaking into a rich man’s house and there’s some violence described as well. After the gig the other night in London, a man came up to me and said ‘I didn’t clap for that song, I thought that song was wrong, it felt wrong that people were clapping, just because someone’s poor doesn’t give them the right to break into someone’s house and hit them.’ I replied to him ‘That’s true’…but it doesn’t take away from the fact that it happens.”

“I’ve never encountered someone saying something like that to me before. No-one’s going to come up to you and say ‘I disagree with the way you think about your ex-girlfriend’! So, you can sound preachy and it’ll affiliate you with politics…left and right thinking. That’s scary, I don’t like it.”

Despite Mick’s reservations about writing this kind of material, I conclude that it must be coming from a place of genuine concern;

“The song that the man didn’t like” he continues, “I’d been watching those riots in Baltimore because of the police brutality. I can’t remember exactly how the song came about but I just wrote this angry song. I don’t have any real experience of it. I was raised middle-class; my parents were both teachers. But not having experience of it first-hand doesn’t mean you can’t understand it or understand the kernel of the feeling…having power and dignity taken away from you.”

I’ve been fortunate to be able to spend time with a great many musicians in the course of doing this job. Almost universally, the greatest satisfaction for artists seems to come from performing their work in front of a live audience. With Mick, however, whilst he clearly finds positives in live performance, his greatest satisfaction and drive seems to come from the craft and activity of creating the music itself;

“You like the way something makes you feel you know?” he answers when I ask what motivates him, “The marriage of a good set of lyrics with a melody that is sympathetic to the message…one where you think ‘fuck, he means what he’s saying.’ It makes you feel something and you don’t understand why you feel it. You don’t understand why it has this effect on you as opposed to some other song that has none at all. There’s no real equation for it, which makes it attractive. You happen upon it if you try hard enough. It’s an interesting business.”

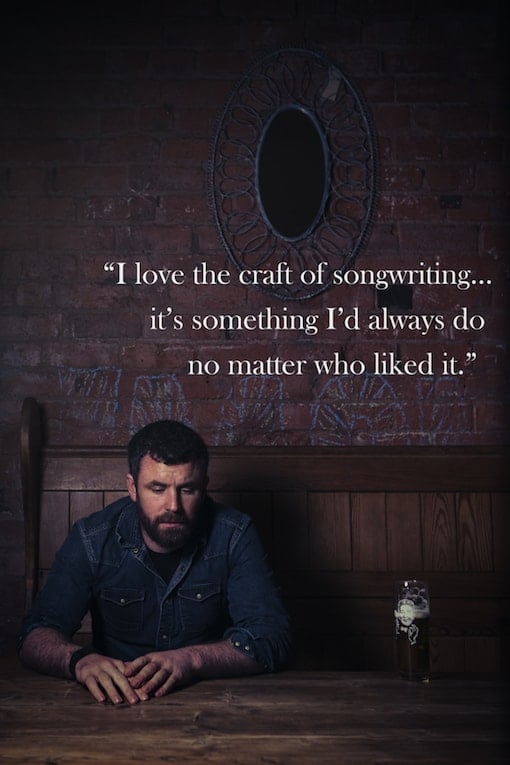

Mick continues; “I love the craft of it. It’s something I’d always do no matter who liked it. The fact that people like it adds another element which is then is enjoyable as well, so I chase that too which leads to compromises sometimes. It can lead to personal compromises where my personality adapts to being on the stage. It doesn’t really appeal to me…getting up and talking in front of people because I’m naturally shy…but because I like doing the music and I like the fact that other people like it then I’ll adapt to it. Then to perpetuate them liking it, sometimes you adapt the music. You present it in such a way that a radio station might play it. But mainly I just like creating it. You have a new friend when you write a song. I can play it to myself, it’s a thing that I made…you can’t touch it, but it exists.”

Mick goes onto discuss the purity of the point at which the creative process comes together; “Nearly all of the songs that I’ve written” he reflects, “I’d say that the first time I sang it through was the best time I ever sang it. Every time after that is diminishing, because that’s when it was formed and raw and you’re naïve to it. Usually nobody hears it. Then after that…I can find myself singing some romantic love song about a girl that I no longer think about, and I could be thinking about croissants in my head! Singing this fucking song…I could be thinking about anything, I can be completely detached from it. That’s what I mean by diminishing.”

As I listen to Mick speak and reflect on the plaudits he’s won throughout his career…for example he’s a Meteor award winner, the Irish equivalent of the BRITS…I wonder how difficult it is to make a living as a performing artist for someone who is so clearly introspective regarding their art?

“It’s a very privileged life, it’s a lucky existence” Mick firmly answers. “Anything that’s difficult about it, I’ve made it difficult on myself, it’s been my own doing. You can always say ‘no’ to something you don’t want to do. It’s times where I haven’t said no, where I’ve got myself into situations where I’ve thought ‘I don’t fucking belong here, I don’t like this, I should have just said no’, but someone convinced me that it was a good idea to do. That usually includes vacuous interviews with people who don’t really give a fuck about music. People who are interested in celebrity or me as a person…in that that’s the subject, not the music…that annoys me. But then, I got myself into that situation. If I had avoided it then it wouldn’t be a problem. There really is nothing difficult about this job.”

Feeling a sudden streak of of self-consciousness as to whether I was one of those ‘vacuous interviewers’, I quickly switch to talking about the more positive aspects of being a musician;

“The creative process is still the best thing about it” Mick responds, “but there are loads of good things about it. You get to meet a lot of very interesting people who have had unique lives. They have good stories. The recording process is very enjoyable; the gig process is enjoyable. From the point of view of a struggling band I’m sure there are a lot of difficulties and hardships…but I’ve been very lucky.”

As we conclude I enquire as to what Mick feels he has learned as an artist over his twelve-year career;

“I’ve learned to be more patient and I’ve learned to just take it easy. There’s a kind of mystery to this business. One phone call could change things at any time. It could be a call that say’s so and so wants this song off you…it’s going to give you two million quid and change your life. If you spend time thinking about that phone call, you’re just wasting your time. If you just take it easy and just take what comes, life is a lot easier. So I’ve learned not to get excited about things in that way…to just go back to what I really like about it. Which is making music.”

Interview and Photos by: Rob Bridge

This article is part of an ongoing series of photo / interview features on Folk Radio UK from Rob Bridge, a photographer, writer and film-maker specialising in folk, acoustic and Americana music. You can contact him on twitter @redwoodphotos

See All Our Photo Interviews Here