We continue our interview with Dave Arthur author of the new A.L. Lloyd biography ‘Bert, The Life and Times of A.L. Lloyd’ which is being published by Pluto Press. You can read part 1 here.

When did you take the decision to write the biography and what inspired the undertaking of this mammoth task?

After Bert’s death in 1982 I was asked to write an obituary for the Folk Music Journal, and a bit later a Radio 4 documentary on his life. These projects required me to dash around the country interviewing a number of Bert’s old friends and acquaintances and looking through, and listening to, a lot of his literary and radio output from the 1930s to the 80s. I ended with a sizeable archive of interviews, many of the interviewees, being older than Bert, died within a few years of my recordings. I felt that it was a shame to just leave them in boxes in my attic, and tried unsuccessfully to find a publisher who would publish a Bert biography. I already had a biography of Gilbert Sargent, an old Sussex countryman, published by Barrie and Jenkins but they weren’t interested in Bert. Lawrence and Wishart, Bert’s old Communist Party affiliated publishers, hadn’t got any money, and neither had Arthur Scargill at the Miners’ Union, so I left the boxes where they were for another twenty years until the Vaughan Williams Library Director, Malcolm Taylor, suggested that the EFDSS might publish it. So I dug out the boxes and set to re-reading all those old letters and files, listening to the voices of long-dead men and women and trying to get my head around it, and to remember names, dates, places, events, that had once been in the forefront of my mind. Anyway, I started reworking and soon realised that there was an enormous amount of research still to do, if I was going to do the job justice. Years rolled by, the manuscript grew and grew. We had a book launch two or three years ago, when it was hoped that I would have finished. No such luck. Eventually I dumped a large manuscript of well over 260,000 words on Malcolm’s desk. At which point we both realised that it was too big a project for the EFDSS to publish. Eventually we succeeded in getting the left-wing academic Pluto Press interested in going in with a joint venture. And the rest is history.

What would you say has been the most challenging aspect of the biography?

Knowing when to stop researching and writing, and how to get fit again after several years of spending many hours every day sitting at a computer and taking little, if any, exercise. It took a good year of dieting, drinking gallons of green tea, and walking many miles each day with my lurcher, Dusty, before I got back into some semblance of shape.

What discovery has maybe surprised you the most?

That I survived long enough to finish the book. As far as Bert is concerned, I was surprised, gob-smacked, astounded, with the range and quality of his accomplishments in so many areas. Folk music was really only a small part of his life-long achievements. He could, had he so wished, have become a success in many artistic and intellectual areas. He really was the archetypal Renaissance Man.

What aspect of Bert’s life have you found the most inspiring?

The dedication and hard work he applied to any task, and his generosity with that most valuable of our possessions, time. He always had the time (or found the time) to help, share and inform anyone who asked for his knowledge and advice.

In terms of myths that have grown up over the years about Bert such as him being asked to join Fairport Convention as a band member what are some of the bigger myths you have dispelled in this biography?

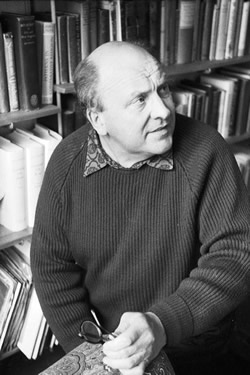

Bert with his books, 1970's (photo: Hedy West)

Your biography set out to give as accurate a portrayal as possible, warts and all, did you find yourself at odds on any revelations, especially as you clearly admired the man?

On a North Sea trawler, 1942 (Photo: Bert Hardy)

I always thought Bert was a very private man and I suppose it would be fair to say that his political connections were never as public as say Ewan MacColl but your biography depicts a very different individual, can you tell us a bit more about this side of his life?

Bert was a very private man, who seems to have kept his life in various self-contained compartments with, frequently, no overlap between areas. You’re correct, I think, in saying that Bert was not as overtly political as MacColl. This, however, in no way meant a diminution of his political convictions and aims, but merely represented the personality differences between the two men. As is quoted in the book, MacColl was potentially a bludgeon man, while Bert would have favoured the stiletto. Bert was much more circumspect in his public pronouncements than was MacColl. MacColl wore his politics and opinions on his sleeve whereas Bert kept them in his back pocket, to be taken out when necessary, but not worn as a badge. MacColl was didactic and bombastic in his edicts; things had to be done his way, and you were either with him or you were beyond the pale. Bert tended to influence things more subtly with ‘suggestions’, encouragement, and by example. He was also, perhaps, more pragmatic than MacColl. For example he could write anti-war lyrics criticising Dunlop’s commercial, exploitative interests in their Malayan rubber plantations, the preservation of which was part of the reason for the Malayan ‘emergency’ in the early 1950s. It wasn’t declared a ‘war’ by the British Government because loss and destruction of property and assets wouldn’t have been covered by insurance companies if a state-of-war existed, however, a less threatening word such as ‘emergency’ had no such negative impacts on the finances of Dunlop and other colonial companies that were so essential to Britain in the post-war years. On the other hand he was perfectly content to take a large fee from Dunlop a few years later to write a booklet on car breaking-systems, that financed several weeks of unpaid folklore research. But he was a hard-line communist from his early twenties when he returned to Britain from Australia just in time for the ‘Hungry Thirties’, the Jarrow hunger marchers, the means test, the rise of the fascist movement in England and continental Europe, and the ‘Battle of Cable Street’ where thousands of East End residents and members of the Communist Party of Great Britain (CPGB) challenged Sir Oswald Mosley’s right to march his Black Shirts through the East End. During the ‘Battle’ Bert managed to get a bicycle wrapped around his neck.

One of the surprising aspects for me was Bert’s contribution and support of the Folk rock movement as well as his devotion to Sandy Denny, is it fair to say that he was a greater advocate of progressive folk music than people generally gave him credit for?

Sandy Denny (one of Bert’s favourite singers)

Of course, it didn’t hurt that Fairport Convention had among its members Sandy Denny (one of Bert’s favourite singers), and Dave Swarbrick, his long-time accompanist, along with Alf Edwards.

Despite his undoubted prejudice in their favour, Bert did feel that electric instruments were capable of providing another emotional dimension to the music, and could create an atmosphere in a large concert hall that would be impossible with acoustic instruments or a solo voice.

He had also been involved years earlier in the experimental use of electronic music as an accompaniment to poetry on BBC radio’s Third Programme, and was familiar with, and had friends and collaborators within, the contemporary and avant-garde music world.

Returning to the actual writing of the biography can you tell us a bit about the lengths you went to to complete the work and the sort of challenges you faced?

A lot of the work was very mundane, such as carefully reading through five-year’s worth of passenger lists of liners sailing from Australia to Britain from 1929 to 1935 to find out exactly when Bert returned from Down Under. The time expended on such necessary, unromantic, work immediately becomes worthwhile when you find a 1930 reference to ‘Lloyd, Age 21, Sydney to London’ with a destination address just a couple of roads away from where he had been living in the early 1920s. But because this was four or five years earlier than the date Bert usually gave for his return to the UK, you still have to go through hundreds of lists for the next five years to make sure that you’ve got the right one.

Playing Harmonica on the Southern Empress, 1937

Research also involved tracking down surviving friends, acquaintances and work colleagues, many of whom were older than Bert, from the 1930s and 40s, and travelling all over the country from Scotland to Cornwall to North and South Wales, and many places in between, often more than once to conduct interviews.

Ultimately, of course, you end up with possibly a hundred hours of recorded interviews, hundreds of books, papers and magazines, and thousands of pages of research information on everything from cycle units of the First World War, physical descriptions of Sydney, Australia, in the 1920s, the history of the Artists International Association, early BBC recording equipment, the plays of Bertolt Brecht, the poetry and murder of Lorca, the whaling industry in the 1930s, Theatre Workshop, the skiffle boom, the Radio Ballads, erotic songs, the training of tank crews in the Second World War (Bert trained as a gunner/radio operator), the folk revival, electric folk, and a hundred and one other subjects, some of which provided only a couple of lines in the final book, some never made it into the book at all, but it all had to be researched and evaluated.

The final and most difficult job was assembling this mass of material into a narrative, that is coherent, informative, original, honest, entertaining and fair to the subject.

Being so well connected to the folk scene as you are what sort of Bert Lloyd legacy would you like to see new folk artists taking forward, if any…and do you still see/hear his influence in music today?

Bert’s legacy is all around us on the folk scene. Even young singers who may hardly know of him will undoubtedly have heard many of the songs he introduced into the folk clubs, if not from his many available recordings, then through the singing of people such as Martin Carthy, Norma Waterson, Fairport Convention, Martyn Wyndham-Read, Frankie Armstrong, Louisa Killen, Bob Davemport, Roy Harris, Johnny Handle, and even myself.

His book Folk Song in England remains an essential read as does his and Vaughan Williams’ The Penguin Book of English Folk Songs, reprinted by the EFDSS in 2003 as Classic English Folk Songs. A follow-up collection The New Penguin Book of English Folk Songs, edited by Steve Roud and Julia Bishop, published in 2012 by the EFDSS, will provide young singers with an abundance of fresh material.

What I’d like to see young artists taking forward is the desire to research original material, to go back to original sound recordings and manuscript collections of traditional songs and tunes and soak up styles and techniques of performance and repertoire, and then with that knowledge go on to interpret the material in their own way. Be original, search out different versions, multiple versions of songs that interest you, don’t simply learn all your songs and tunes from the revival singers of the 60s, 70s and 80s, whose albums are available on CD. Read about the background to the songs, set them in a social and historical context. Check up on words, names, places that you don’t know. The more you know about a song or a tune the more convincing and satisfying will be your performance. Don’t be pedantic and make a fetish out of folk song, there are no right and wrong texts or tunes, musical folklore is always in a state of flux. When that ceases it becomes a mere museum piece, a sad thing trapped forever, unchanging, like an insect in amber, or a butterfly pinned down in a museum case. Be inventive, original, but always from the vantage of knowledge and understanding of the material. Above all don’t take yourself too seriously, be suspicious of all the hype and flim- flam of the commercial music world. Even if in general, folk music is just one more tributary of the commercial music river, try not to treat folk songs and tunes like packets of sausages in a supermarket, to be packaged, hermetically sealed, piled high and sold cheap. They invariably taste like crap compared to free-range organic pork sausages, produced from lovingly-reared happy pigs, by farmers and butchers who care, and understand their trade.

Will you be doing any talks following the book launch?

I’m giving a talk at Goldsmiths College music department on 29 May. A chat at the official book launch at 7.30 p.m. on 31 May at Cecil Sharp House, where everyone is welcome to the free concert, when Frankie Armstrong, Martyn Wyndham-Read and Iris Bishop, John Foreman, Tom Paley, Hylda Sims and the (Revived) City Ramblers Skiffle Group, Peta Webb and Ken Hall, Pete Cooper and Sue Lee, Pete Stanley, and Rattle on the Stovepipe, will be performing.

I’m also talking/being interviewed and possibly singing at the Stoke Newington Literary Festival at 3.00 p.m. in the White Hart pub on Saturday 2 June.

And anywhere else – festival, club, book fair, literary event, bookshop, library – that would like to have me, or me with Rattle on the Stovepipe, to talk about Bert and the book and to play our versions and interpretations of some of Bert’s music from the 1940s to the 1980s. Just get in touch through my website at www.davearthur.net or through Pluto Books at www.plutobooks.com.

Bogandillon, New South Wales, with his favourite pony, 1929.

Get tickets (free) for the book launch at Cecil Sharp House.

All photos Of A.L. Lloyd provided by Dave Arthur and Pluto Books (All Rights Reserved).