Dave Arthur is the author of the new A.L. Lloyd biography ‘Bert, The Life and Times of A.L. Lloyd’ which is being published by Pluto Press. He has gained a considerable reputation as a researcher, collector, writer and broadcaster of English song, music and folklore. He edited English Dance and Song for twenty years, and in 2003 was awarded the EFDSS Gold Badge for services to folk music. His writing has appeared in The Times, the Independent, Melody Maker, Words International, the Folk Music Journal, English Dance and Song, the Stage, Encyclopaedia Britannica and New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians.

To celebate the book launch of ‘Bert, The Life and Times of A.L. Lloyd’ at Cecil Sharp House on May 31st we have a number of features, the first of which is a two part interview with Dave Arthur. In part one below Dave talks about his background: from his introdution to folk music and bohemian lifestyle leading up to his first introduction to Bert Lloyd.

“When everyone else was listening to Cream, I was listening to A. L. Lloyd”. Frank Zappa

“I’m old enough and have been close enough to many of the events recounted in this thoroughly but sympathetically researched book to recognise the ring of truth when I hear it”. Bill Leader, record producer

Dave Arthur Interview: Part one

I’m originally from Cheshire where my grandparents were farmers, butchers, thatchers, builders and sheep-shearers. When my father was a boy he used to go out around Little Sutton and out onto the Wirral as tar-boy with his father who was a self-employed seasonal sheep-shearer. My paternal great-grandfather came from the Welsh slate village of Glyn Ceriog where he bred and dealt in Welsh ponies and horses. He was eventually kicked to death by a stallion he was breaking. My mother was a farmer’s daughter from Heswall on the Wirral. She attended Hoylake School for Girls, was a good pianist and singer and wrote poetry for her own amusement. She encouraged me to read and to listen to music, and to attempt to learn the piano. Unfortunately I was not a good student and soon gave it up. At an early age my mother gave me collections of narrative ballads which I would read under the bed-clothes by torch-light. Ballads such as ‘Hiawatha’, ‘Young Lochinvar’, ‘Dick Turpin’, ‘The Fighting Temeraire’, and Macaulay’s romantic and heroic Roman epic, ‘Horatius’, in Lays of Ancient Rome. She also gave me a set of 78rpm records of shanty singing from which I learned ‘Shenandoah’, ‘Bony Was A Warrior’, ‘Blow the Man Down’ and several others. Being a farmer’s daughter she taught me ‘To Be a Farmer’s Boy’, and popular pieces such at ‘Jeanie With the Light Brown Hair’ and ‘Come into the Garden Maude’.

The Skiffle Craze

We had moved down to London when I was four or five, and I eventually got into St Olaves Grammar School at Tower Bridge. A year or so above me was Martin Carthy and Bert’s son, Joe, and the school actor, Roy Mold, who wisely changed his name to Roy Marsden. The skiffle craze hit when I was around thirteen and I started going to the Saturday night skiffle sessions in the Chislehurst Caves. A year or so later I had met another young lad who was also interested in trad jazz and skiffle and we started to go up to Soho and hang out in the Gyre and Gimble (the Gs), Sam Widges jazz coffee house, the Skiffle Cellar and various other cafes, coffee bars and clubs, including, a bit later, the famous left-wing Partisan, the Nucleus, the Singers Club, and the cellar coffee house and art gallery the Barn in Monmouth Street, in which I ended up working.

Alan Lomax and the Ramblers: Back Row: Alan Lomax, Bruce Turner, Jim Bray, Brian Daly. Front Row: Peggy Seeger, Ewan MacColl, Shirley Collins.

In all these places you could hear music both impromptu and organised from performers of American folk music and the blues such as Davey Graham, Wizz Jones, Jerry Lochran, Pete Stanley, Alex Campbell, Clive Palmer (with whom I spent a summer busking under the arches in Villiers Street and working as a pavement artist outside the National Gallery). Long John Baldry, Marion Grey, Redd Sullivan and Martin Windsor as well as the more left-wing, more trad British Isles material-inclined, group which included Bert Lloyd, Ewan MacColl, Isla Cameron, John Hasted, Shirley Collins, Steve Benbow and Dominic Behan. Also around was a group of very influential American singers – Alan Lomax, Peggy Seeger (who taught Pete Stanley the banjo), Ramblin’ Jack Elliott and banjo picker, Derroll Adams. These last two were a huge influence on many of us younger tyro banjo and guitar players. Many of us adopted the Levi or Lee faded denim jeans (which we had to wear initially whilst sitting in the bath, to shrink them to size), the short black oilskin rain-slickers, and desert boots. Then, our Levin Goliath, Gibson or Harmony Sovereign guitars slung across our backs, we hit the road for Paris, the south of France – or Spain, Which is where I ended up on my first hitch-hiking adventure down to the sun. Mik Paris and I slept on the beach at Sitges, smoked strong, black-tobacco’d Celtas cigarettes, slipped hopeful (but largely unfulfilled) messages of assignation to young holiday-maker girls, sitting outside cafes with their parents, and played guitar and sang Woody Guthrie songs to assuage the wrath of Franco’s military police, who regularly woke us up in our sleeping bags in the middle of the night to demand a song and a cigarette, Life didn’t get much better.

I never went back to school after the summer of the year I became fifteen. I lived, what we called a ‘bohemian’ life (which I think pre-dated the popular use of ‘beatnik’ and ‘beat’) painting, hanging out in picture galleries, playing music, reading a lot of Beat poetry, Rimbaud, Baudelaire and Huysmans and the novels of Steinbeck, Hemingway, James Baldwin and William S. Burroughs, living in communal flats and studios around Soho and Fitzrovia, or sleeping out in the Embankment Gardens at the bottom of Villiers Street (known as ‘the garden of lost souls’) wrapped up in copies of The Times. Not much fun in winter. At weekends in the summer we’d catch the milk-train down to Brighton and sleep on the beach with, hopefully, a young ‘mystery’, live on cold baked beans and dance to the music of Russell Quaye’s City Ramblers skiffle and spasm band. During the week we’d sit around in Soho Square playing guitars and banjos. Life still didn’t get much better.

When I needed some money I’d get a job for a week or two – trainee hearing-aid audiologist, kiosk attendant on platform one of Charing Cross Station for W.H.Smith (the chance to read the Agatha Christie oeuvre!), washer-up, booking agent for Cooks travel agency, theatre booking agent, trainee dental mechanic, bookseller (many times), timber yard labourer, gay-nightclub waiter, coffee bar manager, trainee theatre scene-painter at the Mermaid, and many more. I used to write each job on my guitar case until I ran out of space. At one time or another I worked in most of the best known and most interesting bookshops in Charing Cross Road, Oxford Street and Baker Street, including the famous ‘Bomb shop’, Collett’s Political Bookshop, where I got the chance to spend hours chatting to the famous 1930s Marxist editor, Edgell Rickword, who ran the second-hand department, and who, with Bert Lloyd, had been a co-founder of the famous Left Review magazine, in which had appeared Bert’s first published writing.

Like so many other people we eventually fell out with Robert Maxwell, gave in our notice, and returned to London. We decided to give up academic bookselling for a few months and try and sing full-time before opening our own bookshop. The months spread to years, the years into decades and thirty years later we got divorced, and the bookshop never happened. Although we did collect enough research books over the years to stock a medium-size bookshop.

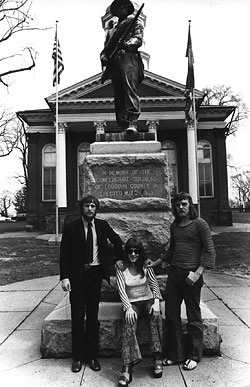

John Harrison, Toni & Dave Arthur, Virginia. 1972

Through these years we toured all over the British Isles as a folk singing duo, and for a short while as a trio with ex-Watersons’ bass-singer, John Harrison, during which time we toured America. We recorded albums for Topic, Transatlantic and Leader. Researched the modern Wiccan religion, thanks to Alex Sanders (the ‘King of the Witches’) and his wife Maxine, looking for connections between folk customs, ballads and dances and the ‘supposed’ Old Religion. While touring the British Isles performing at folk clubs and festivals, we took the opportunity to record the life stories of farmers, gamekeepers, fairground folk, canal workers, clog-makers, Travellers, and, of course, traditional singers, dancers and musicians. Believing that folksong was rarely performed in isolation we learnt clog and morris dancing, broom dancing, bacca-pipes jig, and collected and started telling folktales. After a few years we were given the opportunity to put all this together as script-writers, researchers and presenters for many TV and radio programmes and series for both children and adults. We toured Africa several times for the British Council working in schools and teacher training colleges introducing ways of using traditional song, music, dance, drama and storytelling in education. We worked in Belize for the British Army, singing in jungle camps up on the Guatemalan border. We performed in East Germany, Poland and Russia for the British Peace Committee along with the Marxist art critic John Berger. We spent several years working in the theatre, sometimes with David Wood, writing plays for the Young Vic, Manchester Library Theatre, Derby Playhouse, Nottingham Playhouse, and many more. For three years I was writer-in-residence at the Canon Hill Puppet Theatre in Birmingham writing for puppets, actors, dancers and masks. For a number of years I was deeply involved in martial arts, both oriental and European (fencing, quarter-staff and long-bow archery).

From the 1970s I spent over twenty years editing English Dance and Song magazine, also at various times, Storylines (the magazine of the Society for Storytelling, of which I was a Director) and Animations (the national puppetry and animation magazine at the time).

During the last ten years I’ve recorded several albums for Fellside and Wildgoose Records, compiled a lengthy Bert Lloyd bibliography, worked as a writer, musician and storyteller and toured Hong Kong, France, America, Sri Lanka and Japan. A few years ago I teamed up with fiddle player, writer and Director of the London Fiddle School, Pete Cooper, and guitarist Chris Moreton, to form the Anglo-Appalachian string band, Rattle on the Stovepipe.

Rattle on the Stovepipe: DAVE ARTHUR (banjo, guitar, melodeon, vocals) PETE COOPER (fiddle, viola, vocals) DAN STEWART (guitar, banjo)

Do you still play in Rattle on the Stovepipe or any other bands?

Yes. Rattle on the Stovepipe is my main band, but I also play melodeon for dances in a ceilidh band called Swallowtail with Dan Stewart (guitar) and his sister Sarah (fiddle). Dan and Sarah have been playing together since they were young teenagers and Swallowtail was their band, I joined them two or three years ago.

Rattle came out of the album Return Journey that I recorded for Wildgoose Records several years ago. I’ve always been interested in the cross-over between Appalachian/American and British music, and Return Journey was a musical exploration of the two-way transatlantic connections and influences – morris tunes that morph into banjo and fiddle breakdowns, minstrel songs that were brought to the UK by travelling minstrel shows such as the Christy Minstrels and which were taken up by rural singers in Norfolk, Wiltshire and Oxfordshire, narrative ballads that travelled across to the States with the early emigrants from the UK, and suffered a sea-change, many losing some of their supernatural elements, and some becoming democratised, e.g. the Lord in the ballad of the ‘Gypsie Laddie’ is transformed into Little Billy Lord in our American version. For that album I brought in two friends who also happened to be great musicians, Pete Cooper (fiddle) and Chris Moreton (guitar).We had so much fun making the album that we decided to continue playing together as a band. Our name came from the Canadian lumberjack song ‘Rattle on the Stovepipe’, which we had recorded.

Eventually the logistics of trying to get together to rehearse, with Chris living in Wales, Pete in London and me in Sussex, proved too much, so Chris left. We then invited Dan Stewart to join us, whom I’d seen playing in local Sussex clubs since he was a mere youth, and who also played in a local Old Time band, Old Faded Glory, with my ex-duo partner, banjo player, Barry Murphy. Dan and I swap around between guitars and banjos, sometimes, horror of horrors, playing double (stereo!) banjos with Pete on fiddle. Over the last few years Dan has developed into one of the top two or three Old Time clawhammer banjo players in the UK. Our joint interest in Appalachian Old Time music and British material, and our line-up of guitars, banjos, fiddles, melodeon, mandolin, viola and dulcimer means that we are equally at home playing American Old Time or English songs, ballads and dance tunes.

We are currently putting together a programme of material influenced by Bert Lloyd. Songs he personally gave me (and my ex-wife Toni), little known or unknown songs I found in the Bert Lloyd archive at Goldsmiths College, New Cross, and songs and tunes he recorded over the years and/or published in magazines and books. And, taking a leaf out of Bert’s book (he claimed never, or very rarely, to perform a song exactly as he received it), we have changed some of the lyrics and tunes to some of the songs, using Bert’s versions as jumping-off points from which to adapt the material into Rattle versions. It’s the ‘folk process’ considerably speeded up.

When did you first meet Bert and how close did you become?

I first saw Bert perform in the folk clubs, cellars and coffee bars of Soho in the 1950s when I was a very young teenager, who had left home at fourteen to live in Soho to try and pursue the romantic life of an artist. I was addicted to the Impressionists. I painted and hung around the National and the Tate galleries during the day, and worked in cafes and clubs, washing-up and cooking, during the evenings and often all through the night. I shared this dream with another young south Londoner, Mik Paris (now the eminent writer and modern historian, Dr Michael Paris). It was Mik who introduced me to the music of Woody Guthrie, Jack Elliott and Derrol Adams, and taught me my first few chords on the guitar. I soon acquired a banjo and Mik and I became a duo playing around Soho and following in the busking footsteps of Wizz Jones, Alex Campbell, Davey Graham, etc., down to St Ives in Cornwall, to sleep on the beach, or to hitch down to Paris to hang out at the Bar Monaco, and then on down the National 7 to the south and the sun. Bert was very much a part of the Soho scene along with Ewan MacColl, Peggy Seeger, John Hasted, Shirley Collins, Alan Lomax, Eric Winter, Fred (aka Karl) and Betty Dallas and many others. His influence was already being felt through his own singing and through popular singers and recording artists such as Steve Benbow who, as well as accompanying Bert on record and concert, also sang a number of his songs – ‘Whaling in Greenland’, ‘The Molecatcher’, ‘The Gentleman Soldier’ etc. So, although I knew Bert as a performer and a mover and shaker on the nascent folk scene I didn’t get to know him until the early 1960s when, having got married and working as an academic bookseller, my then-wife, Toni, and I moved to Lewisham, just over the hill from Greenwich where Bert was living in Croom’s Hill.

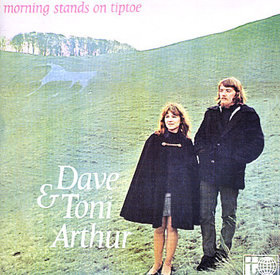

Toni, whom I’d met whilst running a coffee-bar called The Twelve-Stringer, off Wigmore Street, was an ex-Royal Academy trained singer and pianist who could actually read music and sing harmony! We soon retired from real work and started performing as a duo, gradually dropping our American material and concentrating on researching and collecting British traditional songs, music, dances and folktales. It was through this research that I contacted Bert and invited him to dinner to chat about some work I’d been doing on the Derby Ram family of songs. He couldn’t make the date but soon after, on returning from a collecting trip to Hungary, he invited Toni and myself over to listen to the fruits of his expedition. From then on we’d occasionally go over to dinner with Bert and Charlotte, and we’d meet up at clubs and festivals, and a couple of times a year I’d collect him from Croom’s Hill and drive us both up to Cecil Sharp House for meetings of the Folk Music Journal editorial board, of which we were both members.

We were not close friends, more like mentor and apprentices, he was thirty or forty years older than us, and vastly more knowledgeable on all aspects of folk music, and much else. I didn’t realise just how much else until I started working on his biography some twenty or so years later. Unlike Toni, I always felt a bit intimidated by him, although he was invariably friendly, helpful and encouraging. When researching the biography, I discovered that I was not alone in feeling this.